July 25, 2023

2 min read

Key takeaways:

- Severe maternal morbidity rates increased between 2008 and 2018 for almost every racial and ethnic group.

- Births to women younger than 25 years decreased and births to women aged 35 years and older increased.

Population-level severe maternal morbidity rate increases in the U.S. in the past decade were attributable to age-specific rate increases and might indicate worsening prepregnancy health status, researchers reported.

“Because the risk of severe maternal morbidity increases with maternal age, it seems plausible that at least some of the secular trend in severe maternal morbidity might be due to the shift in the maternal age distribution,” Blair O. Berger, PhD, MSPH, maternal and child health epidemiologist in the department of population, family and reproductive health and the department of international health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and colleagues wrote.

Berger and colleagues conducted this cross-sectional analysis comparing delivery hospitalizations from 2008-2009 and 2017-2018 using hospital discharge data from the National Inpatient Sample. Researchers used demographic decomposition techniques to assess whether increasing severe maternal morbidity rates and non-transfusion severe maternal morbidity were explained by population-level increases in maternal age or age-specific rate changes.

Results, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, showed significant increases in severe maternal morbidity rates (135.6 vs. 170.5) and non-transfusion severe maternal morbidity rates (58.8 vs. 67.9) per 10,000 delivery hospitalizations from 2008 to 2018 in the U.S. Researchers noted increases for almost every racial and ethnic group except for non-transfusion severe maternal morbidity among white women and those with unreported race (P < .001).

From 2008 to 2018, the proportion of births to women younger than 25 years decreased (34.1% vs. 24.5%), and births to women of advanced maternal age, defined as age 35 years and older, increased (14.6% vs. 17.9%) in the U.S. The largest relative increases in births to women aged at least 35 years occurred among non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (33.4%), non-Hispanic Black (35.4%) and Hispanic (41.2%) women.

In the decomposition analyses, researchers observed little effect of changing maternal age distribution on severe maternal morbidity trends. Increases in both severe maternal morbidity rate indicators were mainly driven by increases in age-specific severe maternal morbidity rates even among younger women, according to the researchers. Among racial and ethnic groups with the largest increases in severe maternal morbidity, age-specific rates accounted for about 90% or more of the increases in severe maternal morbidity.

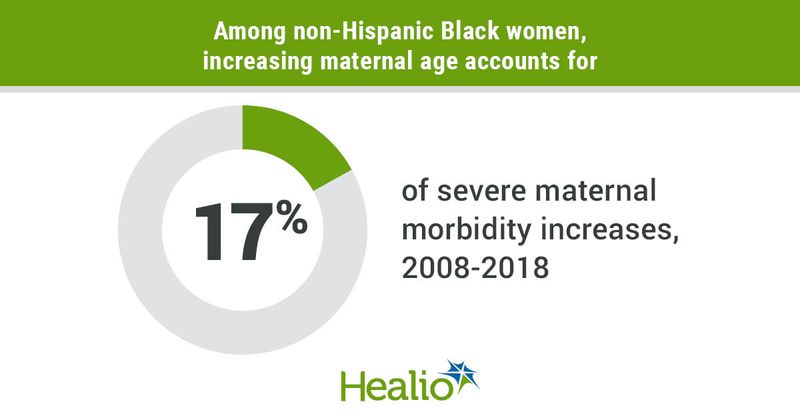

Maternal age shifts had minimal impact for all racial and ethnic groups except non-Hispanic Black women, in which 17% of severe maternal morbidity increases were due to increasing maternal age.

“Our analysis of national delivery hospitalizations showed that increases in severe maternal morbidity between 2008–2009 and 2017–2018 among all racial and ethnic groups combined were not largely driven by the changing maternal age distribution despite shifts toward deliveries among older maternal ages over this period. Rather, increases … were primarily driven by increases in age-specific severe maternal morbidity rates, including increases in the risk of severe maternal morbidity among younger people giving birth. These findings are somewhat surprising given the known risks of severe maternal morbidity that increase with age,” the researchers wrote.

According to the researchers, it is possible that shifts to later maternal ages observed during the study period are not large enough to impact population-level rates or that protective characteristics usually linked to advanced maternal age might lessen the effect of maternal age shifts.

“As delayed childbearing becomes more prominent, especially among demographic groups who historically had births at younger ages, the effect of maternal age shifts could have greater influence on severe maternal morbidity trends,” the researchers wrote.