When Your Own Book Gets Caught Up in the Censorship Wars

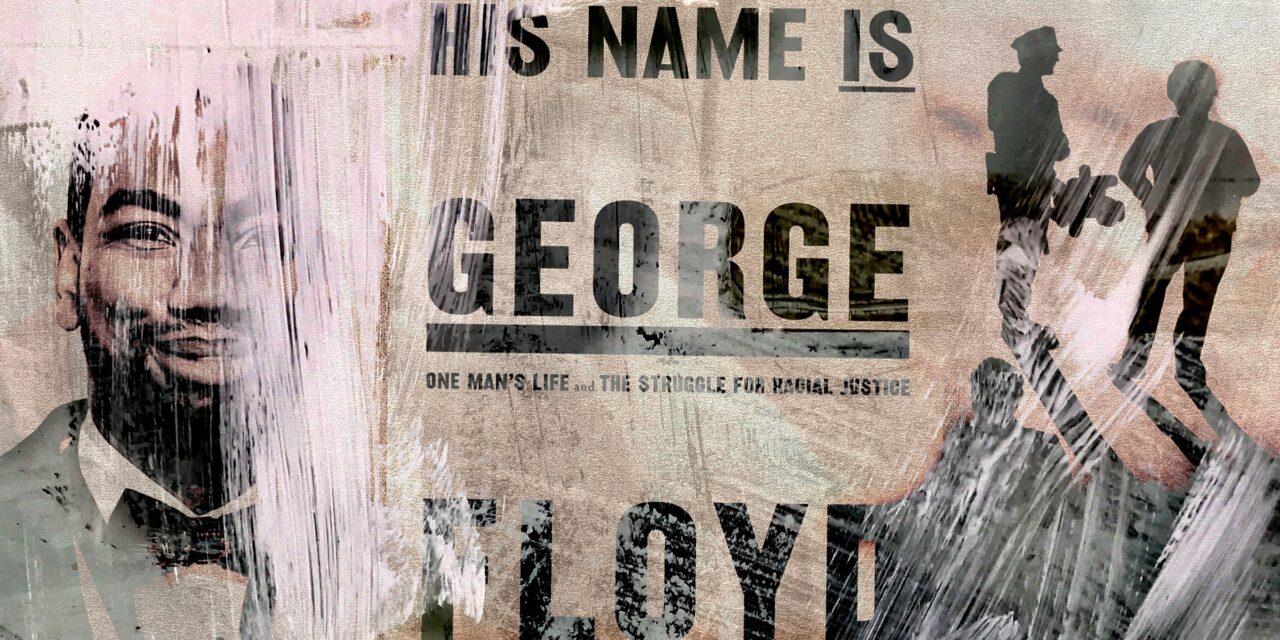

At first, the invitation seemed thrilling. In June, a staff member at Christian Brothers University, in Memphis, Tennessee, reached out to me and Toluse Olorunnipa, my former colleague at the Washington Post, with whom I wrote “His Name Is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice.” Organizers had selected our book for its Memphis Reads program. During the fall, schools and churches across the city would host events that focussed on the themes of the book, which tells the story of how George Floyd’s life and legacy were shaped by systemic racism.

The organizers arranged for Tolu and me to visit Memphis at the end of October. We would give talks at C.B.U. and Rhodes College, whose first-year students were assigned to read the book. The event that excited me most, though, was a visit to Whitehaven High School. Its hallways were filled with young, ambitious Black students, like Tolu and I once were. I imagined them underlining and circling certain passages, dissecting details in class discussions.

That didn’t happen. A few days before Tolu and I arrived in Memphis, we received an e-mail with new information about our visit to Whitehaven. We would be “unable to read from the book directly or distribute the book due to TN’s CRT/Age Appropriate Materials Law.” It appeared that our book had been banned.

In May, 2021, Tennessee became one of the first states in the country to impose legal limits on class discussions about racism and white privilege. The law, passed by the Republican-dominated legislature, prohibits schools from teaching fourteen concepts, including that any individual is “inherently privileged, racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or subconsciously” and that “this state or the United States is fundamentally or irredeemably racist or sexist.” Our book examines the lingering effects of racist policies after Emancipation, in the housing system, the health-care system, the criminal-justice system, and others. It also traces the country’s measured progress toward a more just society, and the enduring patriotism of some of America’s most subjugated citizens—though not enough, it seemed, to avoid getting ensnared in the culture wars.

Last year, Tennessee passed a second, even more subjective law that allowed community members to lodge a complaint if they thought a book in a school library was not age-appropriate. The school board would evaluate the book and determine whether to remove it from the library. It was difficult to imagine a parent at Whitehaven, a school composed almost entirely of Black students, in a neighborhood that has had to confront many of the systemic biases we wrote about, making such a complaint.

A few days after Memphis Reads sent the updated guidance, we got on a video call with Justin Brooks, who helps coördinate the program. He told us that Memphis-Shelby County Schools had concluded that the book violated the age-appropriate law. He wasn’t aware of any complaint from a parent; the school system had acted preëmptively. According to Brooks, representatives from M.S.C.S. insisted that we discuss “gentler topics.” We were told not to connect policies of the past with contemporary racial disparities and to avoid “anything systemic.” “You can’t really go into the weeds,” Brooks told us, which was hard to stomach. The main point of our book was to go deeper than the weeds, to the very roots of racial bias.

Not only were we barred from directly quoting the text, we couldn’t even hand out copies of family-friendly passages that recounted Floyd’s own high-school experiences. Brooks smiled throughout the conversation, but he was clearly exasperated. “We’re trying to work with it,” he said. The program had previously invited many authors who wrote “adult” books, including Dave Eggers, Colson Whitehead, Jesmyn Ward, and Tressie McMillan Cottom. Never before had something like this come up.

Tolu and I made a great reporting team because we have opposite demeanors. Tolu, the Post’s White House bureau chief, is cerebral, understated, and graceful under pressure. I tend to be more expressive. I began to shake my head to ward off a burning sensation in my chest. Could we even attend this event? Would it be a subtle endorsement of censorship to do so? “Justin, this is heartbreaking,” I said.

After the call, Tolu summed it up best: How could you deny an American story to an American student? The students at Whitehaven were about the same age as Darnella Frazier was when she changed the world by recording and posting a cell-phone video of George Floyd’s brutal murder. They lived miles away from where Memphis police officers had beaten the life out of Tyre Nichols.

I knew how events like these could torment a Black teen-ager. In 1999, I was fourteen years old, living in the Bronx, when police officers killed Amadou Diallo, a young Black man who lived on the other side of the borough. Four members of the N.Y.P.D. were in an unmarked car, searching for a rape suspect, when they came across Diallo, who reached into a pocket to pull out his wallet. Police mistook the wallet for a gun and fired forty-one shots at him.

The officers were charged with second-degree murder; they were all acquitted. In my community, the details of the acquittal mattered less than the brutality of the facts. Innocent black man. Shot forty-one times. A simple misunderstanding that could get you killed. The Sunday after the verdict, my pastor called all the Black men in the congregation up to the altar and prayed for their safety. The church ladies handed out pamphlets about what to do if you were stopped by the police. My parents, like many others, warned me that being a Black man was like being an endangered species, that I had to be constantly aware of forces that might harm or even kill me. For a while, I was too afraid to even carry a wallet; I put my lunch money and my Metrocard directly into my pockets. That fear left me embarrassed, shy, angry. I couldn’t understand why, so many years after the civil-rights movement, the color of my skin could be so threatening.

I had once been told that the answer to anything could be found in a book. As a child, I had been introduced to many Black authors by my teachers; I loved the fairy tales of John Steptoe and was captivated by Mildred D. Taylor, whose Logan family wrestled with the racist past—and present—of the Deep South. I was in ninth grade, a student at Bronx Science, one of the best schools in the city, when Diallo was killed. During the next four years, I can’t recall reading anything more than a poem written by a Black person for class. I began to internalize the idea that stories about my community were not worth writing or reading about, that Black authors did not create sophisticated works of literature, certainly not the kind that had a fancy sticker on the cover. Reading “The Scarlet Letter” and “Pride and Prejudice,” especially in the wake of Diallo’s death, made me feel isolated and irrelevant.

One day, during my senior year, I was browsing an airport bookstore when I saw Stokely Carmichael’s autobiography, “Ready for Revolution.” A whole chapter was devoted to Bronx Science, which he had also attended. I was riveted. It started with an officer hassling him on the street, only to be stunned when Carmichael shows him a book with the school’s logo. Although our time there was separated by four decades, we both had the same confusion upon discovering that white classmates had grown up reading an entirely different set of material (in his case, Marx’s “Das Kapital,” and, in mine, Cat Fancy magazine). We were both surprised by how little dancing there was at white classmates’ parties. “It was at first a mild culture shock, but I adapted,” he wrote. I, too, had to learn to adapt, to not be so self-conscious about getting stereotyped because of my speech, my clothes, my interests. It was the first time I had ever truly felt seen in a book that was not made for children.

When Tolu and I began to write “His Name Is George Floyd,” in April, 2021, I wanted our book to do for teen-age Black boys what Carmichael’s book had done for me. I hoped they could relate to Floyd’s ambition—first of becoming a Supreme Court Justice, then a pro athlete—and his constant worry that someone would perceive him as a threat. By describing the accretion of junk science about race differences and the history of use-of-force practices in police departments, I hoped that book would give readers a sense of how that pernicious stereotype proliferated. We even threw in some SAT words.

We also understood that the country’s appetite for talking about race was changing. Tennessee’s governor, Bill Lee, signed the law restricting how racism can be discussed in school on the first anniversary of Floyd’s death. We realized that we’d need to protect our work from being dismissed summarily. We tried to depict the scene of Floyd’s death dispassionately, to avoid being accused of melodrama or exploitation. Some of our most vociferous debates were about quoting people using profanity and the N-word. In high school, I would have been put off by too much of that. “My virgin ears!” I’d tell Tolu, as we reconstructed the dialogue between Floyd and the friends from his neighborhood.

Sometimes, my friends would joke that the book would almost certainly face the wrath of the right wing, as if it were something to look forward to. They figured a polarized response would be good for publicity and sales. But that prediction upset me, and we worked hard to prevent it from happening. When the book did eventually win some fancy stickers—including a Pulitzer Prize—I hoped teachers would consider it worthy of being read in their classrooms.

We arrived at Whitehaven on a pleasant Thursday morning. The building was antiquated, all beiges and browns. Students milled around, wearing clear backpacks—a requirement to deter them from bringing weapons to campus. Near the school’s entrance was a big poster celebrating some of the most accomplished students, who had received hundreds of thousands of dollars in college scholarships. The hallways were lined with senior pictures of previous classes. The farther you walked into the school, the whiter those pictures got.

The school district where Floyd was educated, in Houston, had experienced a similar demographic shift. In the seventies and eighties, white families had fled for the suburbs and other areas, taking their tax dollars with them. The district struggled to find quality teachers and had trouble meeting new educational standards imposed by the state. As we were walking through Whitehaven, Jason Sharif, who had started a nonprofit to help revitalize the surrounding community, told us that the school hadn’t been able to update its science labs in decades. It, too, had to contend with state intervention if it did not meet certain academic standards. At our talk, these similarities were the kinds of connections we had been instructed not to make.

Students filed into the school’s auditorium, and they looked eager to see us. Maybe they were interested in what we had to say; maybe they were just happy to get out of class. I began to discuss how we reported the book. We told them about interviewing more than four hundred people, from Floyd’s friends and family to the President of the United States. I told them we had learned that Floyd was a man of many ambitions, but that he did not find much grace in the institutions that were supposed to help him succeed. There were holes in the social safety net, I said. And those holes were often there because of political choices that were designed to work against Black people. Then I stopped.

“We’re not going to speak for very long because we really want to get to your questions,” I told them. We had expected an open forum, but instead five students had been pre-selected to interview us. Their questions had been vetted and pre-written. The first student, a young woman in glasses who complimented me on my bubbly personality, looked at us and said, “Who was your audience for this book?”

I paused. Briefly, I considered using this an opening to talk about freedom of the press, feeling gagged by the school district, and the long history of denying Black people access to books and reading. (Hillery Thomas Stewart, Floyd’s great-great-grandfather, was a part of that history—he lost five hundred acres of land through tax schemes and paperwork he was told to sign but could not read.) Instead, I told them about my experience reading Carmichael’s book and how much it meant to me as a teen-ager. “I wrote this book for you,” I said.

When the event was over, Sharif announced that the book was available for free. (Penguin Random House had donated thirty-six copies.) Students’ hands shot up, but, because the book wasn’t allowed at the school, Sharif told them they would have to make their way to the mall, where his nonprofit was distributing them. We took a selfie with the students from the stage, after which I had hoped to discuss the restrictions with the assistant superintendent for the district’s high schools, who was in attendance. By the time we finished taking the photo, she was gone.

I had envisioned book bans as modern morality plays—white, straight parents and lawmakers trying to shield their children from the more complex realities portrayed in books by queer people or people of color. But what happened in Memphis wasn’t so simple. Almost everyone we interacted with from the district was Black. No one denied the existence of systemic racism. Their schools were among the first to pilot the A.P. African American studies course and, later this year, they plan to send students to the National Civil Rights Museum in eighth and eleventh grade.

The staff also had to make choices. They were operating in a state whose governor warned teachers to “not teach things that inherently divide or pit either Americans against Americans or people groups against people groups.” Defying that warning could mean losing your job.

Six days after our trip to Whitehaven, Cathryn Stout, the spokesperson for the school district, e-mailed Tolu and me “to apologize for the miscommunication and misinformation surrounding your recent visit.” A reporter from Chalkbeat had been asking questions about what had happened, and she insisted that something must have been garbled during the event planning. The district did not believe in controlling our speech, she claimed, nor would they have objected to us reading from the book.

Stout defended prohibiting the book itself, on the ground that it was not appropriate for people under the age of eighteen. She cited restrictions placed on hip-hop artists, such as Yo Gotti, who have spoken to students but aren’t permitted to perform their music. Gotti’s most famous song is about women sending him nudes; the comparison to our work made little sense. I asked what specifically made the book so inappropriate.

Stout then admitted that no one involved in the decision had actually read it. The district’s academic department didn’t have time, she said. A staff person in the office searched for it in a library database, noting that the American Library Association had classified it as adult literature. That was enough to make the call.

I described this rationale to Donna Seaman, the adult-books editor for Booklist, the A.L.A.’s publication for reviews. She told me the Memphis district’s reasoning seemed “bizarre.” According to her, the “adult books” classification is meant to indicate books of a certain level of sophistication—something not intentionally crafted for children or teen-agers. “This is not to say a sophisticated young person who is interested should not read the book,” Seaman told me. When I checked, many lodestars of the high-school curriculum—“1984,” “The Grapes of Wrath,” “The Great Gatsby,” “Macbeth”—were also deemed “adult.”

I told Stout that I was disappointed that the decision-making had been so superficial. “I hear you,” she said. But she also blamed Brooks, at C.B.U., who had not forcefully protested the decision. Brooks told me that it felt fruitless to try, given all the pressures the school district was under because of the new state laws. He was just trying to put on programming as amicably as possible.

These were the reverberating effects of censorship laws: an academic department in a majority-Black school system casually rejecting a book about the life of George Floyd; nonprofit groups capitulating to avoid causing controversy; writers having to resort to back channels to get information to Black people in the South.

The next day, Stout sent another e-mail. She wanted us to know that the school district had decided to order copies of “His Name Is George Floyd,” so it could be placed under academic review. If the book is deemed appropriate, the district plans to put it in the Whitehaven High School library. She had no idea how much time it would take to make the determination. ♦