© ChayTee – stock.adobe.com

A new study examining the impact of obesity on cardiovascular mortality has uncovered startling disparities and concerning trends in the United States over the past 2 decades.

Findings were published in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Using data from the Multiple Cause of Death database, researchers identified adults whose primary cause of death was cardiovascular-related, with obesity listed as a contributing factor. In total, the study focused on 281,135 obesity‐related cardiovascular deaths among individuals older than 15 years between 1999 and 2020.

The researchers further categorized cardiovascular deaths into 5 main subtypes: ischemic heart disease, heart failure, hypertensive disease, cerebrovascular disease, and other. To paint a comprehensive picture, the researchers calculated absolute, crude, and age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) across racial groups while considering changes over time and variations based on gender, age, and urban or rural residence.

When looking at the crude rate of cardiovascular deaths overall, the study demonstrated a reduction of –17.6% from 1999 to 2020. This rate was consisted across all races in the study, but when calculating age‐adjusted rates, the degree of reduction was greater at –36.0%. American Indian and Alaska Native individuals saw the largest decrease in age‐adjusted cardiovascular mortality at –42.9%, while Black individuals saw the smallest reduction of –31.9%.

However, when looking at the growth of obesity-related cardiovascular mortality, the researchers observed staggering numbers and clear racial disparities. The study demonstrated a substantial 3-fold increase in AAMRs for obesity-related cardiovascular deaths from 1999 to 2020, rising from 2.2 to 6.6 per 100,000 population.

The highest AAMRs were recorded among Black individuals, and American Indian or Alaska Native individuals experienced the most significant rise in AAMRs, with a 415% increase. In comparison, AAMRs increased 300% for Asian or Pacific Islander individuals, 195.2% for White individuals, and 176.2% for Black individuals.

Reflecting on this drastic increase, the researchers emphasized the need for dedicated efforts to comprehend the necessary health and social support for American Indian or Alaska Native populations—which have been historically underserved—that can then inform public health strategies tailored to meet the unique needs of these communities.

“A quarter of American Indian individuals live below the federal poverty line,” the researchers said. “As such, the social determinants of cardiovascular health are of high importance in these communities, driven by inequalities in social structures. A core component of any public health strategy to reduce obesity should include addressing social determinants of health at a community level.”

After analysis of the 5 cardiovascular subtypes, ischemic heart disease emerged as the leading primary cause of death, accounting for 39% to 50% of deaths when stratified by race. The second most prevalent cause of death was hypertensive disease, which disproportionately affected Black individuals, accounting for 31% of deaths in this group compared with 19% to 24% among other racial groups.

Other causes accounted for less than 20% of deaths for each race, followed by heart failure and cardiomyopathy for 8% to 11% of deaths. Cerebrovascular disease accounted for the lowest proportion of deaths at 3% for White, Black, and American Indian individuals, and a higher 11% for Asian individuals.

Additionally, Black women had slightly higher AAMRs compared with Black men, at 6.7 and 6.6 per 100,000 population, respectively. However, for all other racial groups, men comprised a larger proportion of obesity-related cardiovascular deaths and had higher AAMRs, which ranged from 1.2 to 4.6 per 100,000 population for men and from 0.6 to 2.8 per 100,000 population for women.

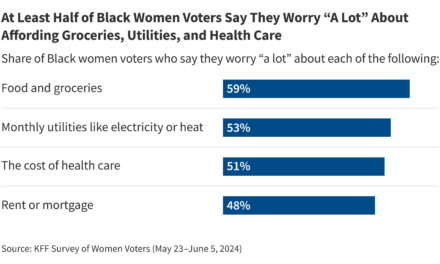

According to the researchers, the observed greater obesity‐related cardiovascular death among Black women compared with Black men is reflective of real-world cultural and sociopolitical contexts.

“Our results indicate that there are disparities in the prevalence and severity of obesity among Black women (with women having greater obesity), which do not exist (at least to the same extent) within other racial groups, and that these disparities translate into greater cardiovascular mortality related to obesity,” they said. “Health care strategies aimed at addressing obesity must tackle as a priority the social determinants that drive health inequalities in Black women.”

Interestingly, the researchers also found that Black individuals experienced higher AAMRs in urban areas compared with their counterparts in rural areas, which contradicts trends observed in all other racial groups.

“A potential explanation for our observations may be higher levels of socioeconomic disadvantage experienced by Black communities in urban areas compared with rural settings, which is driving widening of racial inequalities across several domains including health care,” they added.

Specific health strategies targeted at distinct communities are essential for gaining insight into and addressing the social factors contributing to obesity, the researchers concluded, and these tailored approaches can help reduce the overall burden of obesity and cardiovascular disease on the US population.