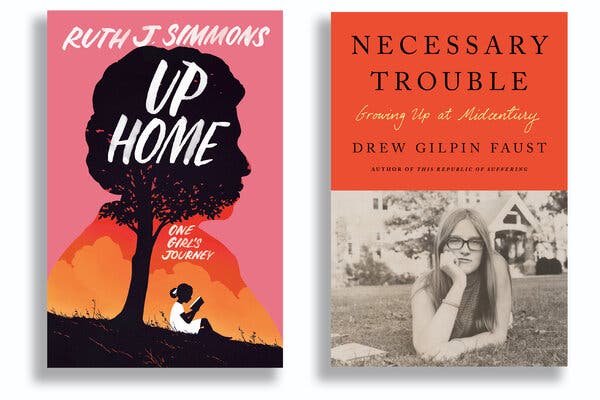

NECESSARY TROUBLE: Growing Up at Midcentury, by Drew Gilpin Faust

UP HOME: One Girl’s Journey, by Ruth J. Simmons

Two baby boomers, both women — one born in 1945, one in 1947. One Black, one white. In 1995, Ruth J. Simmons, the elder of the two, became the first Black president of Smith, one of the largest of the Seven Sisters colleges. But that wasn’t her last first; in 2001, she left Smith to take the helm at Brown University, making history again by virtue of both her race and her gender — the first Black woman to lead an Ivy League institution, which she did until 2012. In 2017, she was persuaded out of retirement to take on the presidency of the historically Black Prairie View A&M University, located in her native Texas, a couple of hours’ drive from where she was born. She left that job earlier this year.

In 2007, Drew Gilpin Faust was named the first woman president of Harvard University, a post she held until 2018. She’s also a historian and the author of six well-regarded books, one of which, “This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War,” was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2009. In a remarkable coincidence, these two leaders have published memoirs of their young womanhood at the same time. Read in tandem, they cast a stark light on how the legacy of slavery played out on both sides of the color line in post-World War II America.

“I was born to be someone else,” Simmons writes in the first paragraph of “Up Home.” “Someone, that is, whose life is defined principally by race, segregation and poverty. As a young child marked by the sharecropping fate of my parents and the culture that predominated in East Texas in the 1940s and ’50s, I initially saw these factors as limiting what I could do and who I could become.”

Simmons maintains this restrained tone as she describes a childhood that could have taken place in the 1850s. She was born in a dilapidated farmhouse, delivered by a local midwife. As the youngest of 12 children, she had a comparatively easier time because she was the baby of the family. But “comparatively” is about as far from ease as you can get. “When my family performed grueling work such as picking cotton, I escaped the worst of being in the fields,” she writes:

My older siblings placed the cotton bolls picked from the plants into sacks they dragged between the rows of cotton. These eight-foot-long canvas bags, sewn by my mother, were sturdy enough to carry me along with the fluffy bolls stuffed inside. Dragging me along on the end of the bag was difficult, but with every hand including my mother in the field, my youngest sisters and I had to be there too. … For most of us, the apprenticeship for cotton picking began around the age of 6.

There was never enough food. The family’s handmade clothing was cobbled together from burlap and rough cotton. Her parents loved her and her siblings but, given the enormous stresses of their lives, also struggled — her father in particular was angry and sometimes abusive (though Simmons focuses on the love and never uses the word “abusive”). There were white people in the vicinity, who, though rarely interacted with directly, were always a menacing presence: “One lived on edge because any of them, no matter their station, could summarily condemn a Black person to injury or punishment.”

In some ways, “Up Home” is a book not of this moment. The word “trauma” never appears; the words “grateful” and “gratitude” appear often. Simmons acknowledges vicious structural inequities — how could she not? Yet she spends little to no time on exegesis of the larger forces responsible for the arduous circumstances of her early life. At first, I was put off by Simmons’s old-fashioned formality, but by the end I came to admire the toughness and grace inherent in her decision to remain moderate and forward-looking. This is who she is. Some might say that she’s running from trauma, that the rage should burn hot. Instead, “Up Home” shows us well how this dignified, powerful woman looks back in wonder at how she got over.

Faust’s “Necessary Trouble” begins with her memory of the night her mother died, Christmas Eve, 1966, when Faust was 19. The two had a tempestuous relationship,and Faust evokes the fury of a neighbor, at a reception after the funeral, who blamed her for her mother’s poor health: “‘You killed her, you know,’ she spat.”

Then, as befits a historian, Faust turns to the larger context, recounting her family history at length. When she arrives at her childhood within the wealthy white community of rural northern Virginia, she describes a key incident in her awakening to the racist milieu into which she was born and with which her family, like most white Southerners at the time, was complicit. In fifth grade, in the car on the way home from school, she hears a radio announcer discussing school segregation. Faust is shocked. “It had never occurred to me,” she writes. “I was not supposed to know or see and yet now I did. … I had to speak. Not to my parents, who had known about this all along and never told me, much less objected to such patent unfairness. I wanted to express myself to someone who might do something about it.”

So, in a letter reproduced in the book’s frontispiece, she did. She wrote to President Eisenhower, pleading with him to end segregation. Her language is that of the determined 9-year-old she was, her shaky elementary school printing faded with time. But shining forth is the resolve to fight for equity that has shaped her life, through her youthful activism as a college student in the 1960s and, later, as a historian of the South.

While Simmons’s book is primarily the tale of an individual making her way over nearly insurmountable obstacles with the help of determined teachers and mentors, Faust, born into privilege (a circumstance she acknowledges and grapples with), mainly chronicles her efforts toward justice, the necessary trouble she made.

The best parts of her book are the vivid stories of her involvement with the civil rights movement and her anti-Vietnam War work. The earnest girl who wrote that letter grew up to be a young woman who in 1965 skipped a midterm exam at Bryn Mawr to join the march at Selma, after she saw television coverage of the murderous attacks on the demonstrators: “If I did not stand up, if I did not act after witnessing this, I would be ashamed forever.”

This anecdote, which charmingly contrasts her college-girl plan to have a friend type up her handwritten draft of a term paper and submit it on her behalf with her awe at the experience of briefly being on the Edmund Pettus Bridge during the march’s second attempt, is a highlight. Less exhilarating to read is the long, nasty letter from her professor that greeted her upon her return, in which he viciously takes her to task for the sloppiness of her paper. In the spirit of the scholar she became, Faust seems to have kept a lot of primary documents.

There are places in “Necessary Trouble” — the title borrows a phrase made famous by the civil rights leader John Lewis, who, shortly before his death in 2020, gave Faust his blessing to use it — where that historian’s impulse to add context and detail slows her narrative down. (She could have dispensed with the long quote from Stephen King about the fear the Soviets’ launch of Sputnik prompted among baby boomers, for example.)

Simmons concludes “Up Home” with this observation: “Thanks to the opportunities granted me to learn, I am not the person I was supposed to be. Rather, I am the person that I dreamed of becoming.” Faust was supposed to have been a Southern belle, Simmons an impoverished sharecropper. It’s our good fortune that these extraordinary women have chosen this moment to tell us how they fought their dreams into reality.

Martha Southgate is the author of four novels, most recently “The Taste of Salt.”

NECESSARY TROUBLE: Growing Up at Midcentury | By Drew Gilpin Faust | Illustrated | 304 pp. | Farrar, Straus & Giroux | $30

UP HOME: One Girl’s Journey | By Ruth J. Simmons | 204 pp. | Random House | $27