The February 2022 cover of Ebony, a magazine that has chronicled Black life for nearly eighty years, features ten young Black women dressed in brightly colored power suits, posed as if preparing for a day of work at the lab. The issue, the latest installment in an annual series on “Campus Queens,” was devoted to “STEM Queens”; their backgrounds and professional aspirations differed, though a reader found recurring themes. There were stories of overcoming hardship: “Many times, we didn’t have a house,” Alexis van Zandt, a twenty-three-year-old biology major, said. “Even in college, when I would go home on breaks, we’d sleep in the car. And I still did what I had to do.” Some offered a “hair hack”; Shia Gourdet, a nineteen-year-old math and electrical engineering major, recommended “oiling the scalp to maintain growth and strength.” There was a pervasive sense of responsibility to achieve. Jamirra Franklin, a twenty-two-year-old health science major, told Ebony, “We need to increase the representation of Black women in STEM, especially in the medical field, so that we can achieve health equity.” Franklin was photographed, arms crossed, beside frothing beakers and vials. “I want to be a change agent,” she said.

At first glance, it isn’t obvious that the issue was part of a campaign in partnership with Olay, the skin-care company. Each STEM Queen received a ten-thousand-dollar grant and a virtual mentorship session with Olay scientists. Olay got front-page promotion. And Ebony secured the funds to run its first print issue since 2019—when Johnson Publishing Company, Ebony’s corporate parent, declared bankruptcy after defaulting on more than ten million dollars in loans.

Partnerships of this kind—Ebony has collaborated with Google, Netflix, Bloomberg, and others—have come to characterize the magazine’s new life under Eden Bridgeman Sklenar. She became the CEO of Ebony and its sister publication, Jet, in 2021, after her father—Ulysses Lee “Junior” Bridgeman, a former NBA player—took ownership for fourteen million dollars, the highest bidder at a bankruptcy court in Houston. As a young man, during basketball’s offseason, Bridgeman held internships at Howard Johnson’s, and he wound up earning his fortune not from sports but in business. After his retirement from the NBA, he amassed hundreds of restaurant franchises, including Wendy’s and Chili’s (at one point, he was Wendy’s second-largest franchisee). When they were teenagers, his children—Eden and sons Justin and Ryan—worked shifts; Eden was a hostess at Chili’s and delivered orders. Eventually, all three came under the employment of their dad. After earning a master’s in entrepreneurship, Eden served as the head of marketing for the family’s company. In 2017, Bridgeman divested his interests in the restaurants, which are now owned by his brother, and became a regional bottler and distributor for Coca-Cola. (In 2018, he attempted to buy Sports Illustrated, but later withdrew the bid.) He also cofounded Manna Capital Partners, a private equity firm that deals in beverages and invests in the healthcare sector.

Ebony marked the family’s first foray into media ownership. “With the right ideas and the right execution,” Bridgeman said when the sale was announced, the magazine could be restored to its former glory. “When you look at Ebony, you look at the history not just for Black people, but of the United States,” he told an interviewer. “I think it’s something that a generation is missing, and we want to bring that back as much as we can.” Speaking with me, Bridgeman Sklenar said, “If you want to understand American trends in life, Ebony is going to be your source, because it’s been that source for its lifetime.”

Stepping in, Bridgeman Sklenar drew upon experience, marketing Ebony as an enticing commodity. “We always knew in the very beginning that we had to find amazing talent in order to reimagine these brands and build a business around this incredible IP,” she told me. She hired people with journalism backgrounds. “Whether it’s been media, restaurants, in hospitality, in the beverage sector, in other industries that our family business is engaged with, we always seek out an employee base that had certain skill sets if we were entering into a new industry,” she said. “This is a formula that we have learned to do over many years.” Her focus was on selling Ebony not so much as a publication but as a one-stop shop for Black upward mobility. That placed brand strategy—Ebony is about “moving Black forward,” as she put it—above more traditional editorial concerns. Bridgeman Sklenar has said her aim is “world domination.” The extent to which Ebony achieves that may make it a bellwether for digital media at large.

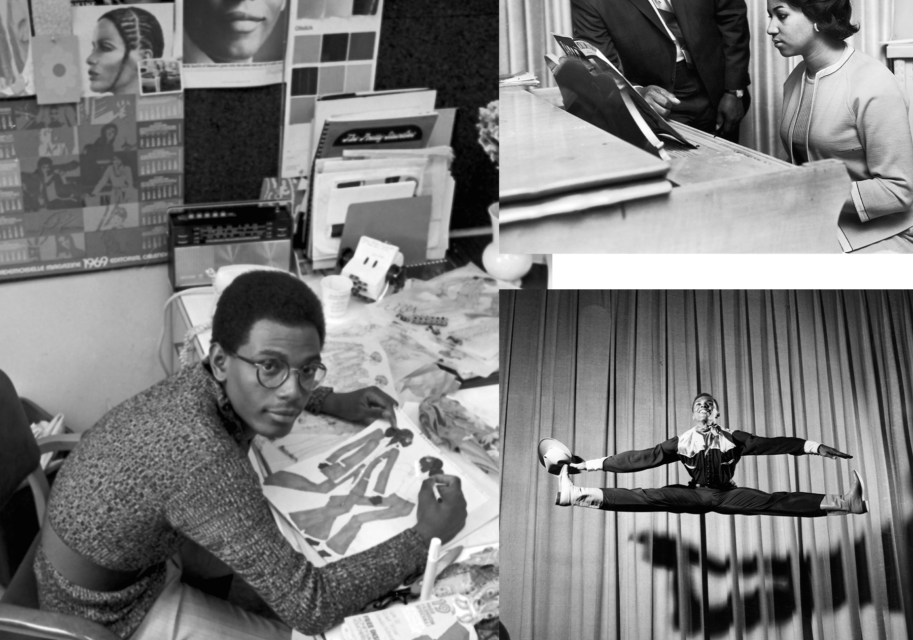

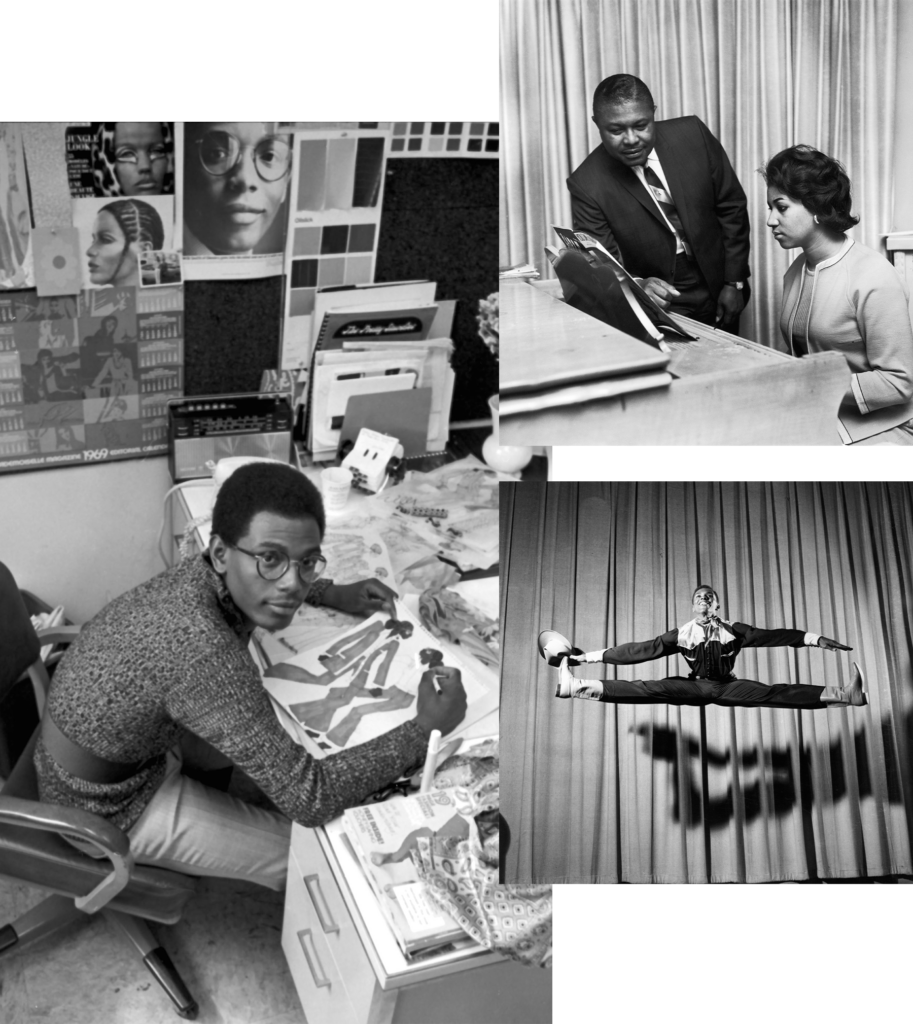

Ebony debuted in November 1945, the brainchild of John H. Johnson, a businessman in Chicago. As he put it, “Ebony was founded to provide positive images for Blacks in a world of negative images and non-images.” The first issue totaled twenty-five thousand copies. Its audience grew steadily; Ebony was one of a kind in producing elite journalism by and for Black people. “Johnson provided prominent writers with an almost unlimited budget to travel,” James West, a historian at University College London and codirector of the Black Press Research Collective, told me. “They could go to places that no other Black journalists could go to on a consistent basis. They had the budget to fly to the Caribbean to do an interview with Amy Jacques Garvey,” a pioneering Jamaican journalist. “They could fly to Africa, or they could fly to London to do a story on mixed-race children.” Ebony’s photojournalism was iconic: images featured stars of African American history—Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Shirley Chisholm—and included intimate portraits—Thurgood Marshall after the birth of his son, Maya Angelou scribbling in her journal in bed. In tandem with Jet—founded by Johnson in 1951 as “The Weekly Negro News Magazine”—Ebony chronicled the civil rights movement. For a 1965 special issue, Lerone Bennett Jr., a scholar and longtime Ebony executive editor, wrote, “There is no Negro problem in America. The problem of race in America, insofar as that problem is related to packets of melanin in men’s skins, is a white problem.” Bill Garland, of the Black Panthers; David Llorens, Ebony’s associate editor and director of Black studies at the University of Washington; and Charles L. Sanders, the magazine’s managing editor, delivered radical provocations on race. And yet, West told me, “throughout this whole period, Ebony is still, at its heart, a quite consumerist, bougie publication.” At one point, Johnson told the New York Times that the magazine’s mission “was not to constantly remind Blacks of racial discrimination but rather ‘to tell them how to overcome it, how to get around it, or, if necessary, how to buy the establishment that refused them.’”

Johnson—whose ventures outside publishing included establishing Fashion Fair Cosmetics, the preeminent makeup and skin-care company for women of color—carefully managed the magazine’s identity, mindful of how Ebony sold itself to the country. “Part of what John Johnson was so smart about is that he recognized that putting out a Black magazine that tends to the Black middle class represented the image of the Black middle class,” Tiffany Walden—a former Ebony contributor, now the cofounder and editor in chief of The Triibe—told me. Until Ebony came along, Black outlets were typically ignored by major advertisers, and instead relied on “local, low-rent, and not very polished” ads, as Brenna Greer, an associate professor of history at Wellesley, put it. “He was really adamant about not putting those in his magazine.” Johnson recruited Colgate and other national brands to his pages. “His magazine was pivotal,” Greer said, “because he showed marketers: this is a viable market and you ignore them at your own peril, whatever your race politics are.” A 1949 issue included an essay, “Why Negroes Buy Cadillacs,” that defended Black luxury spending: “It cannot but do every Negro’s heart good to see one of their number driving the finest car, wearing the finest clothes, living in the finest home. It is a worthy symbol of his aspiration to be a genuinely first class American.” The same issue contained ads for Tampax and Golden State Mutual life insurance, both featuring smiling cartoons of Black people. Producing and circulating the ads, Greer said, “was bringing African Americans into this post–World War II story of what America was, which really was about a middle-class American Dream suburban kind of lifestyle that a lot of African Americans had, but now this included them in the national narrative.” In other words, as Bridgeman Sklenar told me, “Ebony was always a brand”—one that promoted an aspirational middle-class life.

Ulysses Bridgeman—born in 1953 in East Chicago, Indiana—had been among the target audience. His father, Ulysses Sr., was a second-generation steelworker who hoped to keep his son out of the mills. “Ebony kind of stood for Black excellence, showing people doing positive things that could benefit everyone,” as he told Black Enterprise. “It just made you feel good.” By the eighties, Ebony was an institution, with a circulation of 1.7 million and valued at more than a hundred million dollars. Bridgeman settled in Louisville, where his business was headquartered—he had more than ten thousand employees—and raised his family. Bridgeman Sklenar grew up in the nineties, going with her mother to the beauty salon to get her hair styled in tight curls and paging through magazines for news of Black life: Nelson Mandela, Whitney Houston, Michael Jordan, Oprah Winfrey. By the time she was in her teens, she was just under six feet tall; she idolized the Black models in Ebony and imagined herself one day joining their ranks. She continued to follow fashion, but later dropped that dream. “I loved a hamburger a little bit too much to try that hard,” she joked.

The magazine continued to do well financially—by 2006, it reached ten million readers—and built an early online presence. There were tensions, though, between the “old guard” of Ebony editors, West said, and the “younger, more tech-savvy people” on staff. These factions argued over Ebony’s identity in the twenty-first century, including how to incorporate ads on the website. Ebonyjet.com housed print stories; news coverage—mostly on celebrities, occasionally politics—was updated weekly, but sometimes lacked depth. Johnson’s death, in 2005, brought deeper chaos. And, in keeping with the rest of the media world, revenue from online advertising failed to keep up with print losses; Jet started to bleed money such that, in 2014, it was taken out of circulation. In 2015, Johnson Publishing put its photography archive up for sale, hoping to raise forty million dollars.

Ebony and Jet had always been family run—eventually, Johnson’s daughter Linda Johnson Rice became the chair of Johnson Publishing—but, by 2016, the company decided to sell. The magazines went to Clear View Group, a Black-owned private equity firm based in Texas. “We want to grow the digital platform more consistently,” Michael Gibson, the chairman of Clear View Group, said, upon taking over. Within months, however, freelancers began complaining of not being paid on time, if at all; contractors started a viral #Ebonyowes campaign and filed a class action lawsuit that ultimately paid out eighty thousand dollars. In the spring of 2017, the magazine laid off about a third of its staff. The cascade of events not only threatened to shutter Ebony, but also altered public perception of the magazine. Kathy Chaney, who served as managing editor for the print magazine between 2016 and 2018, told me, “There was some disappointment in how a legacy Black publication was handling all of its business.” Some feared the lawsuit would destroy Ebony’s credibility. When bankruptcy followed, the damage threatened to be permanent.

The other day, Eden Bridgeman Sklenar spoke to me from her home office. She is in her mid-thirties, and wore a simple white tank top, her hair pulled back into a ponytail. Large pinups of old Ebony covers were displayed on the wall behind her. All these years, Ebony has kept a headquarters in Chicago, but the team is now completely remote: some staff members are based in New York, she explained, others in Atlanta. Bridgeman Sklenar lives outside Louisville, with her husband, Gregory Sklenar—the executive director of beverages and ventures at the family’s Manna Capital—and their two-year-old daughter. “As someone who has worked in our family business for a number of years, I take a sense of ownership now that Ebony and Jet will have the opportunity to have that same generational succession that it should have had for eons,” she said. (According to an Ebony spokesperson, her father “was the key in the business acquisition and, while not engaged in daily operations, remains a guiding force behind the scenes.” He declined to speak with me.)

When Bridgeman Sklenar arrived, Ebony’s website and Instagram account had gone dark; nothing was happening in print. She set about hiring an almost entirely new staff, starting with Marielle Bobo, who was named editor in chief. Bobo, who had worked a previous stint at Ebony and held roles at Essence and Allure, told me, “We are a legacy brand in startup mode.” On the one hand, she said, the Ebony name guaranteed a certain level of readership and respect. On the other, “the legacy sometimes can be a hindrance.” Bobo recalled an early digital cover on Tobe Nwigwe, a Nigerian American rapper and actor best recognized now for Transformers: Rise of the Beasts, if not so well known at the time. “We featured him first and we gave him that visibility first,” Bobo said. It felt like a risk, a departure from Ebony’s historical preference for household names. Still, she said, “we may also usher in a new era of readers, who might be experiencing the brand for the first time in a new way.”

Since the magazine relaunched, in March 2021, its monthly digital covers have featured sleek video and photography, often focused on celebrities—Issa Rae, Halle Bailey, the cast of The Chi—who provide both a window into politics and culture and opportunities for product placement. The Issa Rae issue, for instance, included a piece on racial representation in the Barbie movie, a listicle of Barbie-esque mansions, and a compilation of “pink hued Barbiecore items” to help readers “channel their inner Barbie.” The rest of Ebony’s editorial content—a combination of celebrity news, op-eds, and interviews with up-and-coming Black artists and entrepreneurs—is not as highly produced or user friendly; reporting is rare. In terms of print—“the vanity piece of content that you’re able to do if all the other things are lining up,” as Bobo put it—there have been two editions, both the result of brand partnerships: in addition to the Olay magazine, a September 2023 issue celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of hip-hop was financed by Google Pixel. Ebony no longer relies on paying subscribers; brand partnerships appear to be a more promising source of revenue, Bobo said. Ebony has also started to dabble in events. “Most of our experiential offerings have been more invitation-only,” Bridgeman Sklenar told me; she plans to host public events in the future. She also hopes to reboot Jet.

On the Ebony site, below a row of magazine sections, and equal in number, sits a lineup of verticals for e-commerce and sponsored content. Notable among them: “SheEO Walmart,” through which Walmart displays beauty products made by Black female business owners. The business owners are highlighted in capsule profiles and on an Ebony podcast, SheEO Business Disruptors; their products are available for purchase through a referral link. Ebony also has a vertical dedicated to its annual Beauty & Grooming Awards: “For several months, our team of staffers and contributors slathered, spritzed, rubbed, and tested hundreds of products so you don’t have to,” an introduction reads. Winners in various categories are crowned with a special logo when an item comes from a Black-owned company, with each product available for sale through a referral link (out to Walmart, Amazon, Sephora). Ebony receives a sum when items are purchased through its site, but a greater source of revenue comes from the beauty companies themselves, many of which pay Ebony to license a physical seal for each product, touting the award. (For the coming year’s awards vertical, Bobo said, “I definitely want to find ways to build upon it by including video and custom social media content—and really building out that franchise digitally, incorporating influencers and other ways to make it more dynamic.”) Within a “Black in Business” vertical, Ebony features “C-Suite Disruptors,” sponsored by Cadillac—a callback, of a kind, to the proud capitalist symbolism of the John Johnson days.

Timeka Tounsel, an assistant professor of Black studies in communication at the University of Washington, told me that she views Ebony’s contemporary brand as one of “rebirth and renaissance.” The magazine is entering a new media landscape while “still committed to speaking to Black people” by “reaching the audience wherever they are, through events, through social media, through scripted content.” Tounsel pointed to Essence as having successfully navigated similar terrain: the magazine publishes online and hosts an Essence Festival annually in New Orleans, which last year lured nearly two million live and virtual attendees. If a successful brand “tells me this product is gonna have my curls popping,” she told me, “I’m going to trust them, because it’s almost like word of mouth.”

Other Ebony readers give the new, corporatized incarnation of Ebony more mixed reviews. “This is a Black consumer product among many, which is great,” Greer told me. She sees signs of improvement: “It’s of a much better quality than what I’ve seen in the last decade.” Charles Whitaker—dean and professor at Northwestern’s Medill School, and a former editor at Ebony—was blunter: the magazine of today is “a shadow of its former self,” he said. “It doesn’t have anything like the reach it had during its heyday, and it barely registers as a cultural conversation-starter or chronicle of contemporary Black life.”

Ebony measures its reach by looking at social media, the number of subscribers to a newsletter sent each week, and time spent on the site daily. By these metrics, Bridgeman Sklenar told me, the brand has been growing steadily since its relaunch. On Instagram, Ebony has about 1.2 million followers; according to media kits, Ebony email subscribers have increased significantly in the past few years, by as many as four hundred thousand readers. (Ebony declined to comment on whether the magazine is profitable, or when it might be expected to get there.) Public analytics, however, suggest that Ebony receives significantly less engagement than competitors—Essence, The Root, The Grio—and that Ebony’s annual revenue is a fraction of what Essence brings in. When we spoke, Bridgeman Sklenar told me, “Digital can’t be the only strategy.” How much do page views matter, anyway? Aiming to expand Ebony through means outside of journalism, her attention is elsewhere: “a complete ecosystem,” as she put it, “that isn’t standing on its own, but part of the overall revenue stream that can keep the business moving forward.”

In the summer of 2019, as part of the bankruptcy, the Johnson Publishing archives were sold for thirty million dollars (ten million shy of the desired sum) to a consortium of philanthropic and cultural heritage organizations including the Ford Foundation, the J. Paul Getty Trust, and the MacArthur Foundation. These groups acquired a formidable piece of history: the entirety of the photo and audiovisual archive from fourteen magazines (Ebony, Jet, and Negro Digest, among others) amounted to a trove of more than four million images, as well as audio and video recordings of Johnson’s television productions—such as the Ebony Jet Showcase and the annual Black Achievement Awards—plus segments from radio stations that Johnson owned. After processing and digitization, the archive will go to the Smithsonian, the Getty Research Institute, and elsewhere, to be made available for public consumption; Steven Booth, the archive manager for the project, told me that his team is now in year two of a seven-year undertaking. It struck Booth that, as Ebony is being memorialized, it is one of the only projects he’s ever worked on that’s associated with an entity still in operation. Though there is no official partnership between his archival work and the rebranded magazine, they’re both “working to amplify the Black experience and Black voices,” he said, and he’s “curious to see how that will continue to play out.”

If, in recent years, Ebony’s future has felt far from assured, its survival seems all the more remarkable given the myriad other contemporary publications focused on Black life—many of them digital natives with more progressive sensibilities than Ebony, with its middle-class suburban roots, ever claimed. Beyond that, as American media has become more racially integrated, the existence of a dedicated Black press has come to mean something different from what it did when, as the writer Brent Staples has put it, “African-Americans were virtually invisible in the white press” unless they committed crimes. Major outlets target Black audiences and promote Black style. Often, doing so becomes a means by which media companies strive to tap into new sources of revenue—an attempt at solvency during tough times for the journalism business, and the very strategy that Johnson advocated decades ago.

There was nothing inevitable about the persistence of Ebony, and the fact that backers keep investing in it—specifically, Black patrons attached to its historical significance—reflects its importance to Black identity in the United States and, perhaps more broadly, what brand power a magazine can have. Yet as Ebony transforms—the editorial team’s direct involvement in partnerships and other business arrangements marks a departure from traditional journalistic norms—so does its brand. “In the old days, we would say that the firewall kept advertisers from having any say in the development of the content we ran,” Whitaker told me. Now that advertising models have changed, he said, “the ethical thing to do is make sure that content is labeled as ‘sponsored’ and acknowledge any other appearances of a conflict of interest. The publisher also should fight for as much editorial independence as possible. The entire magazine shouldn’t be full of sponsored content—because then it’s a catalogue.”

I asked Tounsel whether Ebony’s reinvention makes her doubt its journalistic heft. “When a commercial brand fails to make money, it dies,” she replied. “Black-owned and Black-targeted media are typically in more precarious financial situations than their white counterparts. So when editors are responsive to a brand’s financial reality, they give the brand the best chance at survival.” Besides, she said, lots of magazines are pursuing new revenue streams that represent revisions to editorial and ethical thinking: “It would be a mistake to view the approach that Ebony’s chief editor takes regarding brand partnerships as deviating from standard magazine practice.” As Susana Morris, an associate professor at Georgia Tech and cofounder of the Crunk Feminist Collective, put it, “I think we can have a systemic critique”—journalism, and particularly journalism focused on marginalized identities, too rarely has the money needed to keep the lights on—“rather than a critique that’s simply lodged at the individual publication.”

Tounsel’s interest is in asking: “What is the Ebony of today?” The answer, to Bridgeman Sklenar, lies in refining a brand and finding as many ways as possible to sell it. If the market won’t support incisive reporting and commentary, she wants her audience scrolling on Ebony’s Instagram, reading the website, buying featured products, finding Ebony events wherever they live. The question that guides her strategy is: “How does Ebony become a part of your everyday life?” Her vision, if not yet realized, is vivid in her mind. “You’re going to the Ebony experience for creative content that’s making you think and expanding your idea of possibilities of upward mobility—whether it’s career relations, financially, whatever it might be,” she said. “We are part of your mindset in so many different ways. We really are just part of your world—and for lack of a better word, just dominate.”

Mary Retta writes about politics and culture. Her work can be found in New York magazine, The Atlantic, The Nation, and elsewhere.