This column is the second in a series by Leslie Gray Streeter about the realities, stigmas and outright lies surrounding single motherhood. Read Part 1, about why she was afraid to be called a single mother.

Angela Washington made peace with the fact that she would likely never be a mother. As a woman in her mid-30s, she’d experienced fertility issues and “didn’t think it was going to happen for me.” Being the matter-of-fact person she is, she accepted it and moved on.

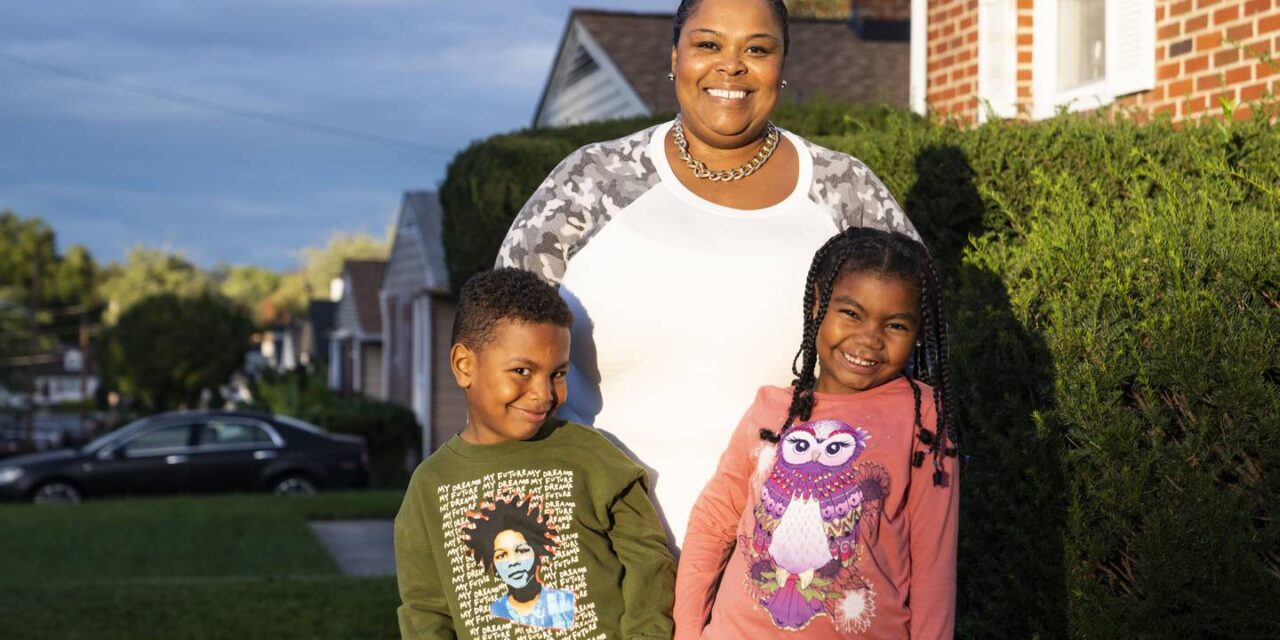

Nearly two decades later, Washington is sitting with me on the stoop of her Gwynn Oak home, watching her kids Faith, 6, and Julian, 5, pose gleefully for photos on the lawn as their adorable pug, Biggie Smalls, sits beside her. Washington took in her daughter and son as babies and eventually adopted them after their birth mother, a close family friend, was unable to care for them. This had not been the plan, but you know that saying about God laughing at our plans.

In 1980, about 40 years earlier, then-29-year-old Bobbie Hargrove also decided to parent alone. She’d been in a serious relationship that never quite seemed to emotionally progress but resulted in pregnancy. “He would ask me to marry him, and then follow that up with, ‘Are you sure?’” remembered Hargrove, now 71.

When she found out she was pregnant, she felt expected to try to make the relationship work, but accepted that it would not. Her choice to end it and parent alone “was not popular,” Hargrove said. “People said, ‘There must be something wrong with her. In the ‘80s, that was not the way it was supposed to be.”

I think many presume that single motherhood, in any capacity, is not the way parenting is supposed to be. “People didn’t see us as a family, and they felt very free in saying that,” Hargrove said. The sharp pain somewhere between my heart and my gut when she made that remark is why I am writing this series on single motherhood in the first place. Whether you come to single motherhood intentionally or unexpectedly, like me, there is no one right way to do this.

Some people think raising a child without a partner is incomplete, like someone cut a man out of your proper family portrait and now there’s just a gaping hole. But what if, as in the case of Hargrove and Washington, you chose to enter this massively hard state of motherhood as the primary parent, completing your family as you see fit? Neither one of them were banking on one day marrying and having someone with which to share the load equally. They were committing to the buck stopping with them. And it’s worked.

In other cases, the desire to be a mother is greater than perceived solo difficulties, so women seek out donors or adopt alone. Single Mothers by Choice, an organization formed in 1981, has connected with more than 30,000 women in various stages of the process, from curiosity to actual motherhood.

It’s hard, though, to find definitive statistics on mothers who parent alone by choice. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, about 51% of single mothers have never been married, but it’s hard to tell how many of them had previously been in steady relationships with the fathers of their children that didn’t last, or if they began solo parenting purposely.

The National Council For Adoption said that between 2017 and 2019, almost one-quarter of adoptive parents were single women. And Cryos International, which bills itself as the world’s largest sperm and egg bank, says on its website that 50% of its sperm bank customers are single women — a number that research suggested had increased following the early days of the pandemic. Dating can be terrible, and some women just don’t want to put off parenthood waiting for the perfect partner.

When I think of single mothers by choice, high-powered attorney Miranda Hobbes from “Sex and the City” comes to mind. In an on-again, off-again relationship with bartender Steve, she’d intended to terminate her pregnancy before changing her mind and deciding to raise her son, Brady, alone. Her eventual marriage to Steve ended in an unsatisfying way in the series reboot, but there was something refreshingly pro-choice about the moment she entered single motherhood, because, well, she chose it.

Reality, however, is not a TV fantasy. Miranda was a rich white woman with a law degree, a nanny and a co-parent who, while not on her financial or professional level, owned a bar. Hargrove and Washington are both Black women in Baltimore. Both have had good careers, but there is a stigma attached to being a Black single mother that doesn’t always get the proud feminist edit that someone like Miranda does.

In the intro to this series, I wrote about my own negative reaction to being called a single mother for the first time, not long after my husband died. A friend, who knew I was writing a book about widowhood, connected me to a friend of hers, also a widowed writer, to see if we might help each other. This was the first time it was suggested my single motherhood of this toddler who I’d raised since he was 6 months old, but whose adoption was not yet completed, might be a choice. I was still in that disoriented, first stage of grief, where nothing was real but my pain and my child, and Brooks was very active at the table with us. You know, toddler stuff.

My dining partner, in his 70s, looked at me politely and slightly annoyed. “So how do you feel about being a single mother?” he asked. It took me a minute to realize what he was actually saying. “Wait,” I said. “Are you asking if I’m going to give him back?” He got real quiet, because I think he was. Some people don’t get adoption or single motherhood, and because he understood grief, maybe he thought my struggle would be eased if I didn’t have a baby to focus on.

Keeping Brooks alive was literally the only reason I wasn’t at that moment having leftover fried rice and bourbon in bed for breakfast. My love for him was not a choice. He was my child. Even though I hadn’t planned parenting this way, I was in.

In 1980, when Hargrove got pregnant, “it was taboo to have a child out of wedlock,” she said. “I was expected to fail.” At the time, she was already challenging expectations in her career in information technology, a field where there was a dearth of Black people and women. She nodded knowingly when I noted that this was only six years after the passing of the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, which gave women the legal right to open bank and credit accounts in their own names.

Although she knew she could handle things financially — to the point where she formally went to court to turn down support — a lot of people couldn’t figure her out, so they made wild assumptions. They speculated that she might be gay, or that she was a thirsty single gal “looking for someone to take care of my child, to take care of me. They absolutely ignored that I was doing OK, that I was living up to my responsibilities,” Hargrove said.

She and her child, local theater actor J. Purnell Hargrove, were fine, even though, as she said, their family didn’t seem ideal. It also affected how other families interacted with her. “They would say things like, ‘I would invite you to this event but you don’t have anyone to bring with you,’” said Hargrove, who suspected that the real reason for the lack of invitations was that married female friends thought she was after their men. She was not. “I’ve had women say to me, as they hold onto their husbands and boyfriends, ‘This one belongs to me,’ and I’m like ‘You’re welcome to him,’” she laughed.

Washington has also had “people make a lot of assumptions” about how she came to be a single parent, many of them loud and wrong. There was the guy who disagreed with some “feminist” point she’d made in a Facebook thread, “trolled my profile, and saw a picture of me and my kids and wrote ‘You just want someone to take care of those kids of yours,’” not knowing she was voluntarily taking care of them just fine.

The circumstances through which she became a parent is called a kinship arrangement, where children are adopted within family or close friends, although Black families have been raising grandkids, nieces, nephews, cousins and neighbors informally for generations. (My own son was adopted from within my family.) “My grandmother fostered, and my mom raised my cousin’s child,” said Washington, who works in human services and once worked in foster care.

The children’s birth mother is someone Washington’s family loved and tried to support through her struggles. But when the children were removed, they “all saw it coming” and stepped in to help. While the two older children went to their grandmother, Washington was asked to take the babies. By that time, they had already lived with her and her family off and on, but she hadn’t considered a more permanent situation.

After all, she had decided she wasn’t going to be a parent. “I had a friend from college who adopted as a single mom, went out to Las Vegas and got the baby. I always said, ‘I can’t imagine doing that,’” she remembered. But now, in a crisis, Washington had tiny people who needed her. “I asked my mom, ‘Are we gonna do this?’ I had to really, deeply think about that, and if this was the best thing for them,” she said. The answer, she thought, was a temporary yes. She did not want to adopt because “I naively hoped their mom would get them back.”

Sadly, the children’s birth mother died before that could happen. As the family grieved, Washington faced a monumental decision. “I certainly could have said I don’t want to keep them permanently, but I was so afraid someone would adopt them separately and gut their relationship,” she said. So, at almost 50, she officially became the mother of these kids she already loved.

Anyone who’s raised children knows that however they come to you, real life is not easy, even when it comes with a Hallmark Christmas movie-worthy plot like that. “People say, ‘You’re doing such a good job,’ and I say ‘Thank you for saying that but I don’t feel that a lot of the time,’” she told me, as my kid joined hers and they giggled from the backyard trampoline. “It’s a lot of laundry, a lot of food. I think ‘What was I doing with my time before I became the mother of two? I could have ruled the world!’”

I am the first person to tell you that single parenthood runs much smoother with help, advice and someone to laugh or cry with. Washington has her parents and sister, while Hargrove had platonic male friends that she calls “my ride or dies.” There’s a lot to admire about what they took on, but neither are patting themselves on the back for doing what they felt needed to be done.

“I knew how she [the kids’ birth mother] felt about me, the love she felt for me,” Washington said, “and I wouldn’t have wanted anyone else to raise them. It just makes sense.”

Hargrove is even more direct. “All I was doing,” she said, “was taking care of my child.”