When American History X was released in 1998, 25 years ago, it warned of a gathering storm of white supremacist violence. The indie crime thriller garnered both praise and criticism, but also a measure of suspicion. Some critics took exception to what they viewed as its “bombastic” tone and “red-meat melodrama,” as though the film’s racist zealots looked more like caricatures than anything that could have sprouted from the multicultural soil of US democracy.

Warning: This article contains descriptions of extreme violence that some may find upsetting

More like this:

– 12 films to watch in November

– The murders nearly erased from US history

– The film that caused a US moral panic

In the film, a thriving neo-Nazi movement recruits charismatic leaders, scapegoats immigrants, exploits the unprecedented connectivity ushered in by the internet age, and capitalises on long-festering racial grievances in white families – all of which combust into open racial warfare. It opens in Venice Beach, California, where teenager Danny Vinyard (Edward Furlong) alarms his Jewish high school teacher, Murray (Elliott Gould), by writing an encomium to Adolf Hitler that praises him as a civil rights hero. The black headteacher, Dr Sweeney (Avery Brooks), gives Danny an ultimatum: study under his wing in an ad hoc course called “American History X,” or face expulsion. Danny’s assignment is to analyse how his older brother, Derek (Edward Norton), got swept into the neo-Nazi Aryan Brotherhood and ended up in prison.

Edward Furlong stars as teenager Danny Vinyard, who is ordered to take the American History X course to avoid expulsion (Credit: Alamy)

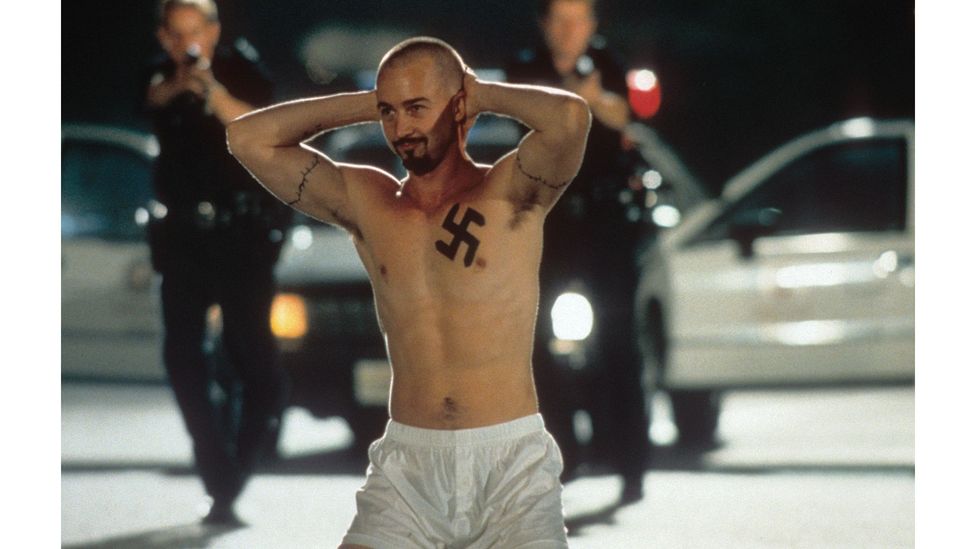

Derek’s crime was an act of intense brutality, portrayed in gut-wrenching detail. In a monochrome flashback, Derek, clad only in white boxers and black military-style boots, his chest emblazoned with a swastika tattoo, shoots two black men in his front garden who’d been trying to steal his car in a turf-war retaliation, killing one instantly. The other, wounded but still conscious, lies sprawled in the grass and Derek proceeds to kill him by stomping his head on the kerb. Soon after, police sirens arrive to bathe Derek in shimmering light, and he raises his hands behind his head in an almost messianic pose of martyrdom. From this pivotal moment, the film traces the circumstances that kindled Derek’s rage and shaped it into racialised grievances, the hollow disillusionment that follows, and his uncertain quest for redemption.

Writer David McKenna drafted the script in six weeks as the 1992 LA Riots, set off by the Rodney King beating, raged outside his apartment. After finishing a second draft, he consulted with Tony Kaye, a British ad director who had been tapped to direct his first feature film. Kaye led McKenna to a skinhead party where the screenwriter took down information from a white nationalist. “For a half hour I talked to a guy with an M-16 tattooed to the side of his head. It was pretty intimidating, if not terrifying,” recalled McKenna. After shooting on the film wrapped, Tony Kaye’s behaviour went from mercurial to outright bizarre. At meetings with New Line Cinema representatives, he brought along a religious retinue of a rabbi, a priest, and a monk in a strange bid to convince executives that his film was not a commercial product but a prophecy.

But a real fight began when Norton inserted himself into the stalled editing process to cut a version of the film that added 18 minutes to its runtime – and played to rave responses from test audiences. In a jealous fury, Kaye dumped $100,000 into paid advertisements in the Hollywood press savaging what he saw as duplicitous meddling by his lead actor. When the studio moved forward with Norton’s cut, Kaye fought to strip his name from the credits, and finally filed a $200m lawsuit against New Line, which was ultimately dismissed. A decade on, Kaye admitted his ego got the best of him: “Whenever I can, I take the opportunity to apologise to all the people that I aggravated. I was doing my best, it was my passion, but I was still completely in the wrong.”

Challenging a persistent myth

A brilliant film emerged from these skirmishes – but its core insight still takes work to unpack. For generations, a persistent myth that black families were irreparably broken by sloth and hedonism had been perpetuated by US culture. Congress’s landmark 1965 Moynihan Report, for example, blamed persistent racial inequality not on stymied economic opportunity but on the “tangle of pathologies” within the black family. Later, politicians circulated stereotypes of checked-out “crackheads” and lazy “welfare queens” to tar black women as incubators of thugs, delinquents, and “superpredators“. American History X made the bold move of shifting the spotlight away from the maligned black family and on to the sphere of the white family, where it illuminated a domestic scene that was a fertile ground for incubating racist ideas.

Edward Norton plays Danny’s brother Derek; the film traces the origins of Derek’s rage and his quest for redemption (Credit: Alamy)

In flashbacks to the Vinyard dinner table, Derek’s firefighter father, Dennis (William Russ), rails against affirmative action – government policies designed to remediate historical inequities – as an affront to meritocracy and rages against the erosion of the white-authored literary canon. Later, after his father is killed putting out a fire at a crack house, Derek steps into his dad’s shoes to lambast immigrants as parasites and cast Rodney King as a drug-addled thug.

When his own family disintegrates, Derek attaches himself to a surrogate family in the Aryan Brotherhood, where he’s drawn to father figure Cameron Alexander (Stacy Keach), who preys on his insecurities and grooms him to become a lightning rod for disaffected youth, even as Derek’s girlfriend Stacey (Fairuza Balk) eggs him on to violence with racial slurs.

Derek’s fate as a paranoid loner seeking kinship from extremists closely paralleled disturbing trends in the 90s. “Lone wolf” terrorists, far-right paramilitary groups and religious extremists were involved in an escalating series of violent events – a deadly standoff in Ruby Ridge, Idaho, between federal agents and right-wing fundamentalists in 1992, the Waco Massacre the following year, and the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 that killed 168 people – that involved perpetrators who were estranged from their families or from mainstream society. American History X accurately predicted how white power extremists would in the years ahead prey on alienated white men from broken families searching for camaraderie and purpose.

When his own family disintegrates, Derek attaches himself to a surrogate one in the Aryan Brotherhood (Credit: Alamy)

Elliott Gould, who portrayed schoolteacher Murray and the would-be boyfriend of Derek and Danny’s mother, Doris (Beverly D’Angelo), tells BBC Culture he initially thought he was reading the script for a comedy, akin to Charlie Chaplin satirising Adolf Hitler in The Great Dictator. Then he got to the kerb-stomping scene. “I realised, this ain’t no comedy, it’s a horror story, and my role, sitting at that dinner table, was to help the audience feel that bone-chilling recognition of hate. Murray knows what Nazis are capable of – the dehumanising contempt that paved the way for pogroms and worse in Europe – and he sees that Doris has buried her head in the sand. He’s the only one who’s not afraid of Derek because he knows the stakes of this conflict.”

‘Holding a magnifying glass up to racism’

For Heidi Beirch, an expert at the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism, American History X is personal. She grew up down the road from Tom Metzger, notorious Klansman and founder of the White Aryan Resistance – and the model for Cameron, the film’s toothpick-chomping, white power patriarch – and she watched childhood friends be pulled into Metzger’s orbit.

“This movie got so much right at a time when leaders were out to lunch about this threat,” Beirich tells BBC Culture. “The way it digs into sentencing disparities, racialised police violence, the impotence of educators in the face of gangs, the powerful siren call of a charismatic demagogue to disaffected youth, even the ways the Vinyard’s family economic decline gets warped into a racial grievance – it was like looking into a crystal ball and seeing the future of white supremacy.”

The striking thing, in Beirich’s view, is that once on-the-fringes views have now entered mainstream politics. “You now have millions of people who subscribe to the QAnon and the Great Replacement conspiracy theories… it’s astounding, on one level, but it’s also strangely unremarkable because of how deeply far-right ideas have filtered into acceptable politics.”

Dorothy Roberts, a sociologist who has devoted decades studying anti-black tropes, tells BBC Culture that American History X was revelatory in how it held a magnifying glass up to racism within white households – but that the film was also guilty of reproducing damaging myths about black people.

“Changing hearts is important, but that alone doesn’t dissolve the legal and institutional barriers that maintain racial inequities,” says Roberts, who argues the narrative is crafted to invite forgiveness of Derek because he ultimately decides to challenge his younger brother’s racist ideas. “The resolution becomes all about white redemption and loses track of the fact that racism is deeply entrenched in American society in ways that can’t be undone by just tearing down some white-power posters from a bedroom wall.”

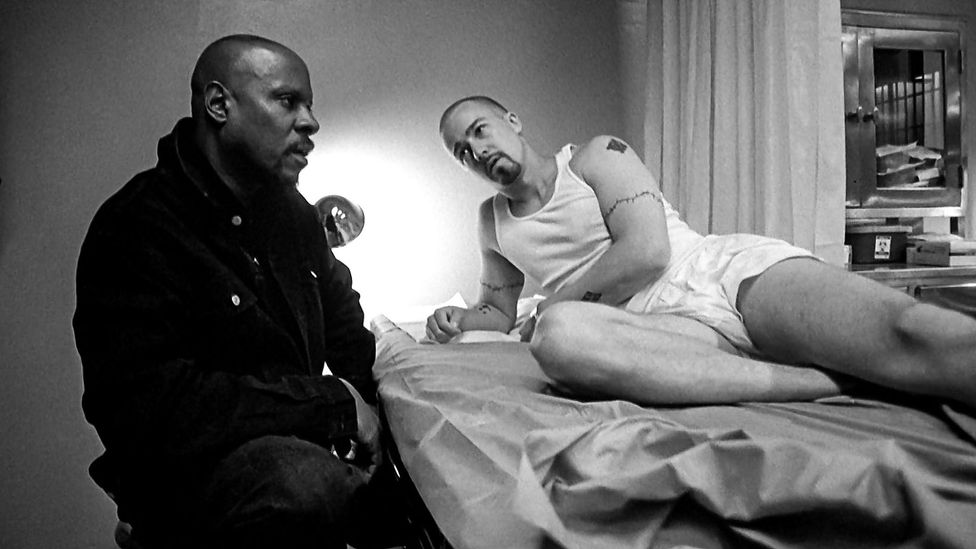

But the more insidious message, in Roberts’s view, is that the burden is on black people to tame their rage as a pre-condition of addressing white supremacy. She points to the character of Principal Sweeney, the educator and outreach worker who guides Derek out of white supremacist ideology after he’s brutally gang-raped in prison, as a stock figure, what Spike Lee termed the “magical negro,” whose mystical wisdom and unstinting sympathy usher white protagonists to redemption. “Sweeney – patient, conciliatory, civilised – becomes the foil against which to demean gun-toting black hoodlums, who are portrayed as the malignant equivalents to white supremacists,” says Roberts. “It’s as though black people must clear an impossible bar of respectability before they earn the right to be free of hatred and violence.”

The film hinges on a brutally violent, pivotal moment that results in Edward Norton’s character’s imprisonment (Credit: Alamy)

If American History X fell into the trap of distorting the realities of black lives, it was not alone. While it’s true that the 1990s saw a surge in films from black producers and directors – including Spike Lee, Julie Dash, and Carl Franklin – they were largely overshadowed by blockbuster films with embedded racial stereotypes, such as Frank Darabont’s The Green Mile or Disney’s Aladdin, and, as Nafkote Tamirat has observed, movies that stripped history of racial exploitation from their conflicts so “audiences could enjoy the tragedy without the guilt”. Viewed against this backdrop, American History X was that rare 90s film that confronted a threat to US society that the mainstream culture was by and large unable – or unwilling – to face.

So in what ways did American History X predict the resurgence of white nationalism in the present-day US? Alexandra Stern, author of Proud Boys and the White Ethnostate, and Andy Campbell, author of We Are Proud Boys, agree that the internet’s chat rooms, message boards, and tweet storms acted as a potent accelerant for the alt-right – fulfilling what American History X explicitly described as the future of radical organising. They also note that zero-sum racial thinking – the very same rhetoric Derek uses to pit racial groups against each other in an imagined battle against white degeneration and demise – drove the birth of the alt-right around the time the US’s first black president was elected in 2008. Then it launched the Proud Boys in 2016, when Donald Trump galvanised large swathes of the country by characterising Mexican immigrants as “criminals” and “rapists”. The Proud Boys went on to become central players in organising the deadly Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017 and to be among the first to breach the Capitol on 6 January, 2021.

What American History X failed to anticipate, in Campbell’s view, is that “snowballing [right-wing] extremism in America” would flow into mainstream politics. Some commentators would argue the opposite is true – that it is extremism on the political left that has exacerbated racial division with critical race theory and “woke” policies. But as far as Beirich is concerned, American History X did presage the story of the US in the 21st Century – it just didn’t go far enough. “Many of the same views that made neo-Nazis pariahs in the 90s are now held by sitting members of Congress in the Republican Party, and that’s something not even American History X saw coming.”

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.