Uncovering new narratives

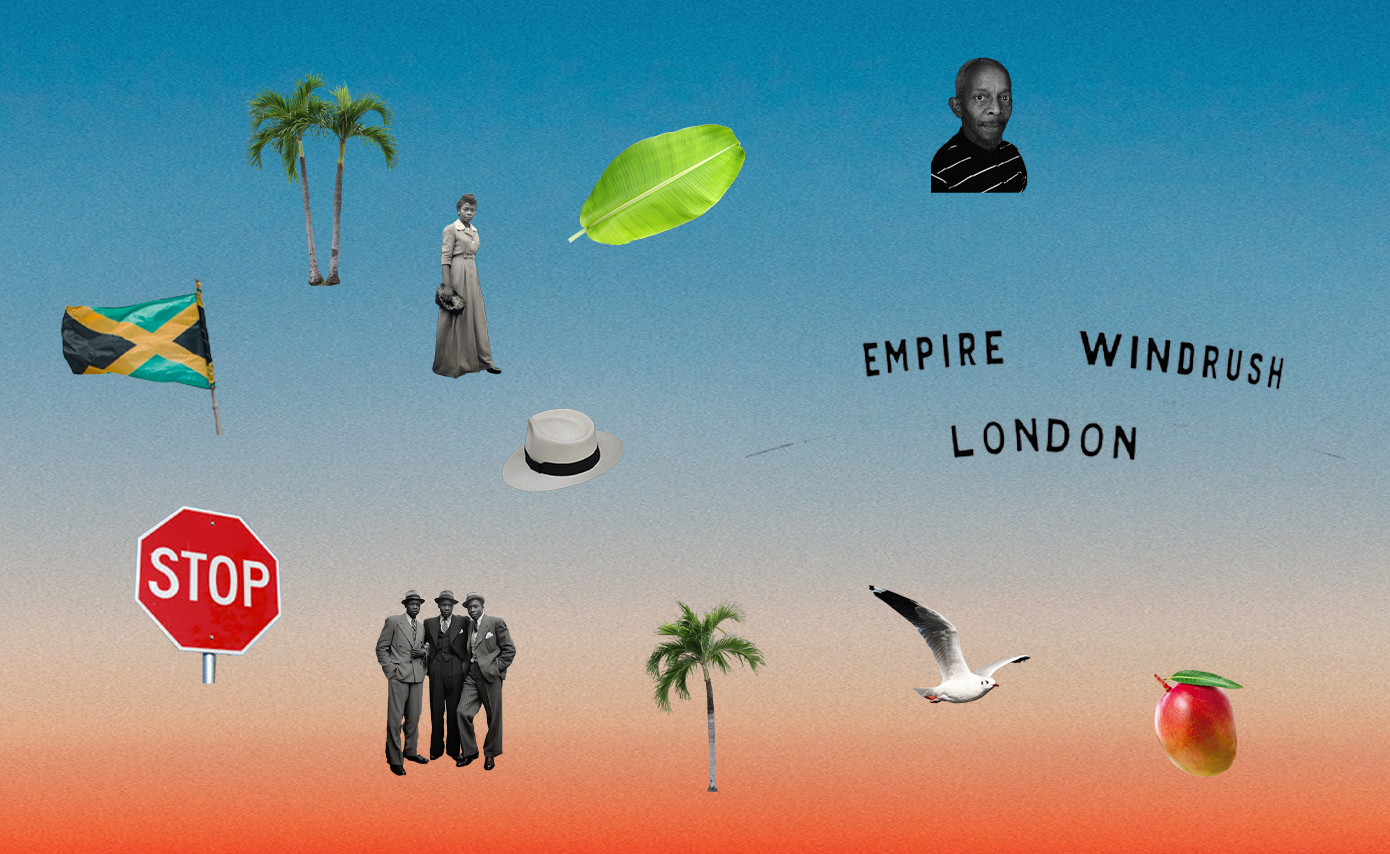

But if we move away from traditional ways of documenting history, and instead look at oral history and ordinary people, Black queer stories can be found. For example, I recently discovered the incredible story of a safe haven for Black gay men in Brixton. Pearl Alcock was a bisexual Jamaican artist who ran an underground bar (or shebeen) in Brixton in the basement of her women’s clothing shop.

The shebeen, which later became a cafe, was a queer safe spot for many Black gay men who travelled from across London to have a drink and a dance, free from racism and homophobia. Alcock’s story has been preserved by the people who knew her and although some might not deem Alcock’s shebeen and cafe as activism, it’s an important part of London’s Black history which is being kept alive by ordinary people.

Similarly, both Akpan and Thompson acknowledge individuals who impacted the Black queer community in the day-to-day. “There were everyday actors who poured into that community,” says Akpan. “We don’t necessarily know their names, but we have their insight and we can build upon that.” As Thompson puts it, “people that just go about living their daily lives,” are “a part of history.”

In order to document perspectives like these, Thompson and writer Jason Okundaye created Black and Gay, Back in the Day: a digital archive and a podcast which documents the lives of Black queer people in Britain through photos submitted by the community. The project is focussed on counteracting the ways in which Black, queer experiences have been erased from celebrations of LGBTQIA+ History Month in the UK

“During LGBTQIA+ History Month in this country, the narratives, experiences and contributions of the Black, queer community are sorely missing and completely absent, apart from a few really well-known people.” Thompson explains. “We set up [the account] because we believe that Black, queer people are not recognised and seen in Black History Month and we weren’t seeing them in LGBTQIA+ History Month either. We wanted to fill that gap.”

Projects like Black and Gay, Back in the Day, mark a tide change: one where the role Black, queer people have played in history is finally being acknowledged. “I think the younger generation who are coming up are curious about the past,” Thompson explains. “What runs alongside that is an older generation who are ready to tell our stories.”

This intergenerational sharing of stories and experiences is how we can redress the absences, silences and gaps around the queer, Black community – people who have always been here, shaping history, but who have been overlooked for just as long. ‘‘We, as a community, are responsible for preserving our history,’ Thompson concludes. “To interpret, analyse, and share it.”’

Thompson’s right. Telling these stories is essential because they broaden the scope of the Black British history we think we know. Pearl Alcock’s life tells the story of Black queer nightlife, the work of Ivor Cummings goes behind the scenes of one of the most recognisable moments of Black British history and the legacy of Ted Brown’s activism shines a new light on the fight for LGBTQIA+ rights in the UK.

Black British queer history is Black history, it’s my history. I’m owed it, and we should know it.