Growing up in the Deep South,

I was never at a loss for the sound

of a man’s voice talking. Their voices

poured forth fire and brimstone

from the pulpit, showered directives

down at children over the school

intercom, cajoled from the campaign

trail, and coerced and corrected from

the head of the dinner table. But

countering the centered and linear

voices of men were those of the Black

Southern women who reared me.

Their conversations stood decidedly

outside and underneath the frame

of masculine discourse. Their voices

swelled outward in circles on front

porches, gathered around kitchen

tables, and rang like bells in the safety

of hair salons. Although the content of

their conversations was rarely found

advertised on billboards or airwaves,

their messages were embodied and

moved from speaker to listener in an

unbroken chain of wisdom.

To be in conversation with

Black Southern women is to be in

conversation with the Blues herself.

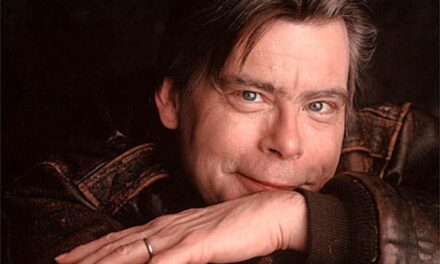

In her art, the musician Rhiannon

Giddens extends an invitation into

the blues to listeners far beyond

the bounds of Dixie. Her music is a

rejection of linear time and bottom-lines. It evades genre even as it

leans into the generations of folk

music crafted by people living at the

margins of society. Her music remains

rooted in tradition while shunning

stagnation. To listen to Giddens’s

banjo is to enter into conversation with

ancestors tracing back to both sides

of the Atlantic. Her blues makes time

travel not only possible, but probable.

Giddens liberates the modern listener

from the confines of a head-centric

culture and renders the otherwise

muted body alive. It centers the flesh

in the now. Like any blues woman

worthy of the title, Rhiannon and

her blues cut through the mind of

dominant culture and require the body

to sing, to think, and to speak.

After roughly two decades of an

acclaimed career as a folk musician,

frequent musical collaborator, opera

and ballet composer, children’s

book author, and podcast host,

Giddens released You’re the One,

her first album of all original songs

this summer. We spoke from our

respective travels in Italy and

Washington, DC, ahead of the album’s

release and her upcoming tour.

Adia Victoria For an artist like

you, there’s a meditative quality to

your music; I sense you embodying

the songs that you’re writing, and

you lean into such traditional sounds

and textures. I’m wondering what it’s

been like to navigate that dissonance

between our fast-paced world—where

technology makes us believe that we

are able to take on so much and be

everywhere at once—and the timelessness of the music and art you create.

Rhiannon GiddensIt’s really

strange. There is such a dissonance

between the art that we make and the

world that we’re forced to peddle it in.

We’re relied on to create this connection to a noncapitalistic world—a world

of human emotion, a world of connection, a world of history—and yet, we

have to do it as soon as possible,

preferably yesterday, please. There’s

a lot of artists out there who are really

trying to make music in an older sense.

We all know there are people out there

who make music to sell, to fit that

box. No shade on it. It’s hard to say

people haven’t always done that, but

technology has changed things so fast

and so furious that there are different

approaches to music that have never

been. All of this to say that it causes

great conflict in me. So far, with the

mission that I’m on and the attention to

what I’m trying to do with my music,

I’ve managed to keep going. But I have

to fit my music around the work that I

do. I fit composing around it. I wrote

the opera Omar at 11:00 PM when

the kids were in bed, or at 2:00 PM, in

between the soundcheck and the show,

or at 6:00 AM, before the kids got up

to go to school. That’s how I do it, but

that’s also just how Black women do it.

I hear people say that they went to

the mountains for two weeks to write

a song, or that they got a grant to go

work for a month by the sea to be

inspired. I’m like, What the hell is that?

I’ve had to fit my creative world into the

world of “keep the lights on.” I’ve been

working since I was fifteen, and I don’t

know how to not work. I support my

nuclear family in various ways, and also

my extended family. When artists say

they’re not on an album cycle, I’m like,

What is that?

I’m getting there, but it’s not

something that we are taught to do—to

take the time that we need to take for

ourselves, for our art. We can’t a lot

of the time because we got to, you

know—

AV You got to feed the baby. (laughter)

You’re talking about this system that

encourages, in the algorithms, quantity

over quality. For me, it’s not a question

of whether I can write songs quickly.

People have been writing songs quickly

since they’ve been releasing music.

If you look back on Printers Alley in

Nashville, people would just go and

bust them out. But now there’s instantaneous feedback and algorithms are

setting you aside in certain categories

and playlists. You’re able to objectify

your music and see it as numbers,

streams, lists, likes, and comments. I

started releasing music when social

media was blowing up in 2016, and that

was almost soul-crushing. I’ve never

known a relationship to my fans, my

community, and the public, outside

of this highly data-itemized, scientific

way of viewing my music and getting

feedback on it. I’ve had to take some

time away from that to remember why

I picked up a guitar and started writing

poetry in the first place. Yes, it is to

receive feedback, but it wasn’t to be in

a feedback loop with people.

What you’re saying about time and

your relationship with labor made me

think about how difficult it is for us as

Black women to accept rest. I thought

about Toni Morrison when she wrote

Beloved (1987)—she had two young

boys and always carried around a legal

pad. She was always writing. She

would wake up early in the morning

just to have those few hours when

her mind was still clean and clear.

Our relationship with rest and labor is

completely different than that of white

women and white women who are

artists. This is how I eat, this is how I

sustain myself, this is how I stay some-

what sane.

I also want to talk to you about time

traveling, which is something that I was

thinking about while listening to your

new record with my mom on the drive

up to Washington, DC, yesterday. My

mom said, “Rhiannon sounds like she’s

singing from a distant past, but it’s also

clearly of this moment.” What is your

relationship with linear time? How does

time figure into the work that you do?

RG I want people to feel both of those

things—the past and the present. I

feel like I inhabit two worlds at once.

I have this deep-seatedness in past

ways of relating to the world, past ways

of singing, and past ways of making

music, but in the present. The thing

is, I do that because it’s the DNA of

where we are now. It’s an excavation

in order to understand more about

now. It’s always been—and always is—

that Sankofa: the idea of going back,

fetching it, and bringing it forward. It’s

not enough to stay in the past. I never

want to be an actor doing a retro thing.

I’ve always known that I was born in

the right era to do what I do. I’m really

appreciative that I have the opportunities and the allies that I have. But in

terms of where popular music is in

America, I was born forty years too

late. The idea of the artist as an interpreter of music who gets up on stage

and performs all these different styles

that used to be mixed up together

doesn’t exist in the same way as it used

to. When you look at Nina Simone’s

records, Odetta’s records, they had

everything on them. They had folk next

to the blues and jazz. That collection

of styles in one record—like in my new

album—is not new. But that was a more

accepted thing back in the 1960s.

Even the way that I make music

is not very compatible to this current

world. It took me fourteen years to

write You’re the One. Granted, I was

doing other things during those fourteen years. It’s not like I was sitting

around, writing a song a year. But in

terms of this kind of songwriting, I’m

not prolific. It’s like you said, some

people can write a song a minute, and

that’s cool. I’m not that kind of songwriter. I edit in my head, and when I sit

down, the music just comes—the poem

becomes the song. There’s no, I’m

gonna write ten songs until I get to the

good one. It’s just the one.

The songs on my new album represent a period of time when I was actively

thinking about what it felt like to write

something that Aretha Franklin would

have sung in an alternate universe. What

does it feel like to climb inside a Dolly

Parton song when she was writing those

first few albums in the ’60s? I would ask

myself questions about the past and the

future mingling in the now and then be

inspired to write something.

Still, I am glad that I live in the

present because I have all of that

behind me to pull from, and also the

opportunity to do something like Omar,

because the “Here, write an opera,

Black female banjo player!” wouldn’t

have happened back then. I accept

the strides that have been made while

recognizing that some of them are now

being taken back.

In the following conversation, Rhiannon Giddens and Adia Victoria discuss the rise of fascism and international solidarity, what it means to connect with music from different cultures and lineages, and the importance of stewarding the sounds and traditions of Black resistance.

Subscribe to BOMB or purchase our fall 2023 issue to read the complete interview now.