Wren, along with the Alameda Health System, which operates Highland Hospital and other community health centers, and the Alameda County Public Health Department, launched the program in 2020 to address the alarming rate of pregnancy-related deaths and complications affecting Black women. So far, the $3.5 million public-private initiative has served more than 200 patients who qualify for Medi-Cal because of their low income.

American women are dying during pregnancy or in the year after at a far higher rate than in other wealthy nations, and Black women are three times as likely to die from giving birth as white mothers.

While California’s maternal mortality rate has been lower than the rest of the country in the last decade, a landmark study of babies born in the state (PDF) between 2007 and 2016 found that childbirth is riskier for Black women, regardless of their socioeconomic status. The study, which examines birth, death and hospitalization records with income tax and demographic data, found that high-income Black mothers have the same risk of dying in the first year after giving birth as the poorest white mothers.

“There are many factors that may be driving this, but the primary factor behind all of that is racism in all of its forms, whether that’s structural or institutional or interpersonal racism,” said Kim Harley, a researcher at UC Berkeley’s School of Public Health. “We see that impacting the whole life course of Black birthing people, and it’s shown in the outcomes that they have during pregnancy.”

More recently, a survey of 2,400 mothers by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that one in five women said they had been mistreated while receiving maternity care. Mistreatment was reported most often by Black, Hispanic and multiracial moms and those with public or no insurance. What’s more, almost half of the women surveyed said they held back in asking questions or sharing concerns with their providers because they didn’t want to “make a big deal” or not feeling confident that they knew what they were talking about.

A unique model of care

BElovedBIRTH combines several strategies, such as having a doula provide nonmedical support during a birth, that has been shown to improve outcomes for Black mothers and their babies.

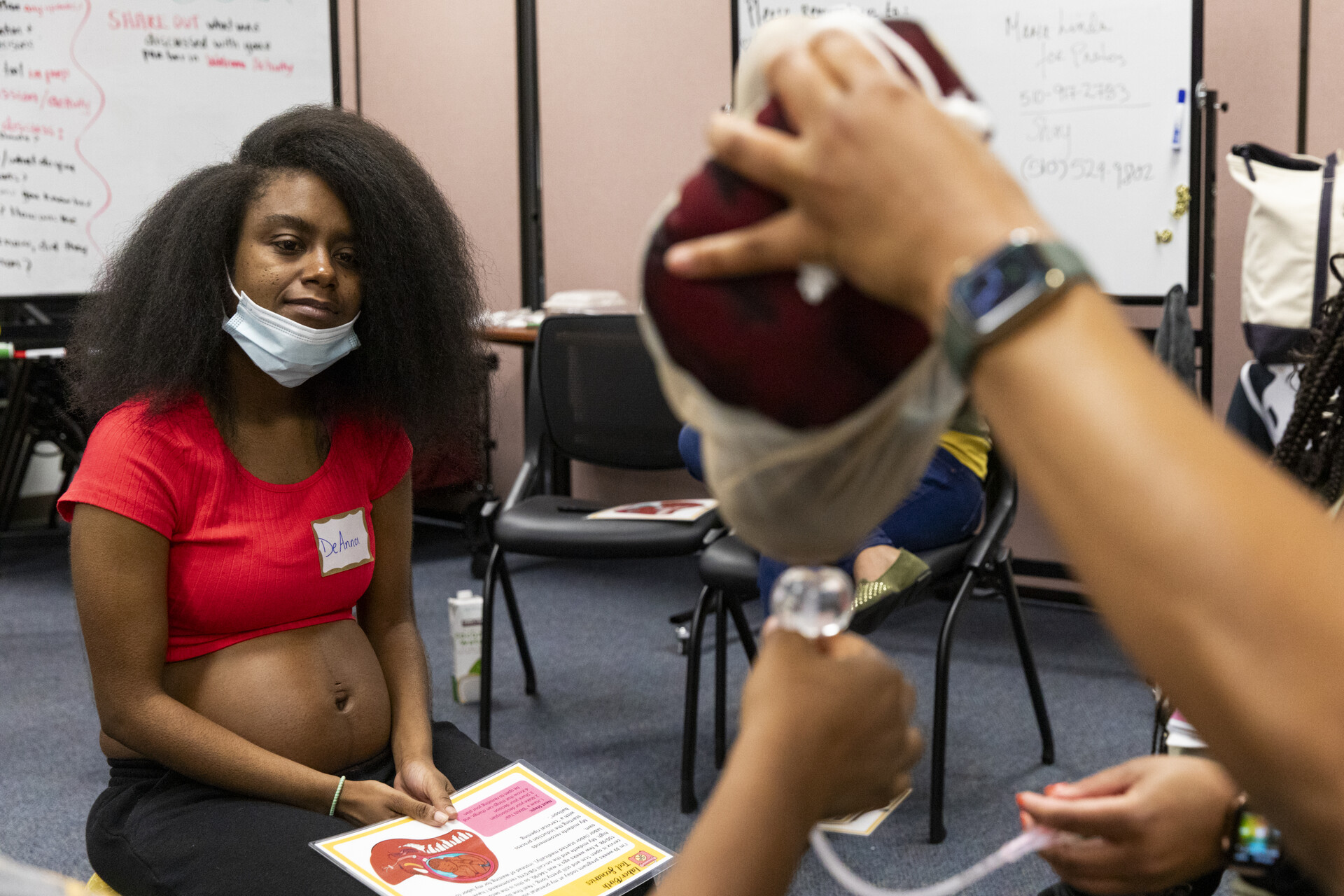

While typical prenatal checkups last about 15 minutes and can leave parents feeling rushed and overwhelmed, BElovedBIRTH takes a different approach. Participants partake in group prenatal care, also known as centering, where they get two hours to learn about what’s happening to their bodies and ask questions.

BElovedBIRTH participants meet twice a month at a clinic located in a former shopping mall in East Oakland, but the setting feels nothing like a medical office. Portraits of pregnant Black people hang on the wall and mellow Afrobeat music plays in the background. There’s a lounge filled with books where women sip tea and chat with each other.