Through several acclaimed collections of essays and poetry, Hanif Abdurraqib has established himself as a tender and incisive voice in contemporary culture. “There’s Always This Year,” his forthcoming book about basketball and his Ohio upbringing, will be published early next year. For CULTURED, the critic time-traveled back to three albums, and three moments in his life, that shaped him forever.

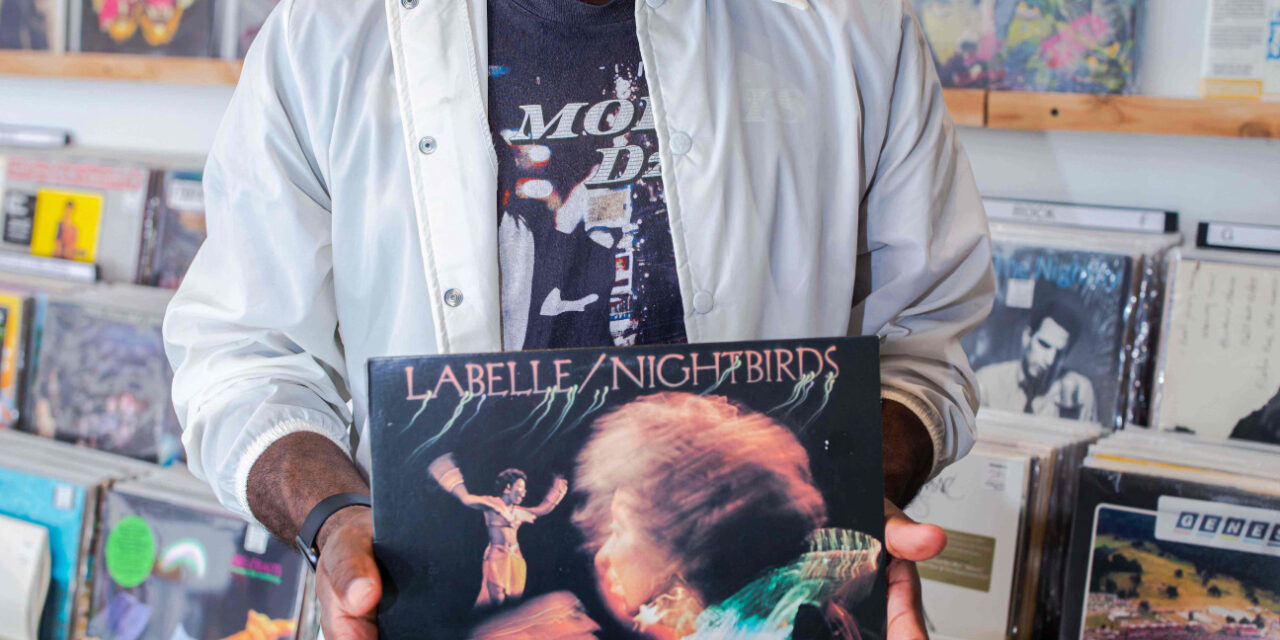

Nightbirds by LaBelle

“I first encountered Nightbirds [1974], not through the sound of it, but through the look of LaBelle. When I was a kid, I saw a photo of LaBelle in their spacesuits on the wall of a friend’s house. Patti is leaning with her face in her palm. I thought, Who are these Black women from outer space? I knew who Patti LaBelle was because my mother loved her.

Nightbirds, for my money—and I think according to critical response, too—is the only good LaBelle album. The other ones are pretty rough, but they’re rough for a reason. LaBelle’s sonic impulses were all over the place. I adore Nightbirds because they found a sound that worked for them. The arrangements were deep in funk and had nice horns, but it’s also an album of sad songs. It’s an album about loneliness. Even ‘Lady Marmalade’ is kind of about loneliness.

Of all the albums on this list, Nightbirds is the one I listen to the most. There are certain albums that I am desperate to show people. One of my greatest pleasures is flipping to side two of Nightbirds—one of the greatest side-twos in music history. It opens with ‘What Can I Do for You?’ It then goes straight into the title track. Then you get ‘Space Children.’

I was talking to a friend, another critic, about a Drake album—I think it was Scorpion—a few years ago. I was like, ‘There are 25 songs here, and I like maybe 10. That doesn’t feel like an album to me.’ He said, ‘So you can just make a playlist of the 10 songs you like, and that’s your Drake album.’ I thought, My job isn’t to make the Drake album. Drake’s job is to make the Drake album.

I guess I’m old school—I always love the physicality of a record. Now, I’m fine to let that go, I can acknowledge that the era of the album as physical object has waned. But that doesn’t mean artists should lose their responsibility for narrative-building, for crafting a sequenced arc of songs, not just a compilation with the occasional hit thrown in.”

Astral Weeks by Van Morrison

“I remember when a new branch of the Columbus Metropolitan Library was built at the end of my street. That meant I could go to the library, sit in a little booth, and listen to CDs all day. I was at the mercy of the library workers who preloaded the CD changers, and I would sit there with a pair of headphones on. One day, when I was 16, I went and Astral Weeks [1968] was on.

I had no idea who Van Morrison was, no idea what I was getting into. Astral Weeks opens, and you’re drifting. It’s that space I really like where you’re almost asleep, but not quite. The phase where you’re awake enough to realize that you’ll soon be in a dream state. You’re still tethered enough to the waking world to relish the anticipation. That’s what the beginning of Astral Weeks feels like to me.

The listening pods were set up along the back of the library, which looked out into deep forest and overgrown grass. I remember listening to the album and staring out at what seemed like endless green. ‘Sweet Thing’ is such an atrociously, offensively beautiful love song. I can’t believe that a person wrote that about another person.

And Van Morrison was like 21 when he recorded it! There’s one line that I love: ‘And I shall drive my chariot down your streets and cry / Hey, it’s me, I’m dynamite and I don’t know why.’ What a beautiful lyric. There’s a certain ridiculousness to it—a love song that lays bare the absurdity of being in love.

I was at a hardcore show like five years ago in Cincinnati. It was one of the old-school hardcore shows I used to go to, where 30 or so very enthusiastic people thrash into each other. There was a point where the guitarist was tuning his guitar, and he started playing the opening notes of ‘Sweet Thing.’ It wasn’t a hardcore version, just a very tender, soft cover. I remember thinking, What an incredible, unlikely place for this song to pop up, what an amazing place for it to live.“

Hounds of Love by Kate Bush

“When I was 18, I had a girlfriend with far more developed music taste than mine. She introduced me to Kate Bush’s sonic leap from her album The Dreaming [1982] to Hounds of Love [1985], which completely blew my mind. I grew up in a household where pop, world music, and jazz were played relentlessly, so I got heavy into the punk scene when I was 17.

Everything I listened to had to be punk, industrial, hardcore, goth, or dark wave. I had repressed my affection for pop, and when I heard Hounds of Love for the first time, it unlocked that. I wish I could relive that moment. I remember it vividly—it was the summer of 2002, and we were at my girlfriend’s house. Her parents were on vacation, so we essentially moved in together for two weeks. It was one of those homes on the east side of Columbus where older Black folks lived, and everything was in its perfect place.

Because everything was pristine, we were confined to the record room, which had this horrendous, thick, lime-green carpet. Her parents had an incredible record collection; it covered the walls from floor to ceiling. Summer was ending, and she was going back to college in Boston. It’s strange when you’re young and the end of something precious is near. It’s not a malicious feeling, more kind of mournful.

I remember listening to “Watching You Without Me” and looking across the room at this person I’d known since I was 11 years old, thinking, Man, we had a good run. It was my first healthy break-up. She’s doing very well. I saw her last month when I did a reading in Boston, where she still lives, and she came with her partner and her kid.

Hounds of Love and The Dreaming create an arc of companionship, feeding into each other. The Dreaming is a very good album, but you can see that it was a stepping stone for Bush. It felt like an experiment that had gone extremely well—daring but playful. I like lush, electric sounds, large extended notes pushed to the edge of breathlessness, and big, swelling crescendos. She had to make something very good in order to learn how to make something perfect.”