Decades of effort to increase Black representation in accounting programs and CPA firms have yet to yield results. Rather than trying more of the same, we the authors believe that a dialogue about the fundamental experience of institutional racism in the profession is the only way to bring about meaningful change. This article, looks more closely at the pieces of the puzzle—messaging, the classroom, and institutional practices—to answer the question of the what the profession can do to address racial equity in the profession and solve the pipeline problem.

***

Following the “racial reckoning” of 2020, sparked by the murder of George Floyd, public accounting firms were very vocal about the ways in which racial equity was a priority for them going forward. Now, three years later, it doesn’t seem like much has changed within the profession—or broader society. Rather, it seems as though things have gotten worse, as the profession has seen a minimal decline in Black representation. We the authors believe this lack of progress has to do with the fact that firms are working harder at implementing the same initiatives (i.e., increasing representation), rather than going back to the drawing board for different ideas.

The brutal murder of Tyre Nichols in the first weeks of 2023 makes it clear that white supremacy doesn’t need white bodies; it only needs warm bodies that are willing to uphold its ideologies. This highlights the systemic nature of racism in U.S. society [which Critical Race Theory (CRT) aims to uncover] and reveals why solely working to increase Black representation in public accounting firms has led nowhere. A more effective method is to adhere to the central tenets of CRT, the first of which posits the centralization and salience of race and racism in discussions of accounting practice within U.S. society. Only through proprietary racial dialogue about the fundamental experience of institutional racism in the accounting profession will effective change be fostered in any meaningful way.

Unfortunately, this is seldom enacted by organizations, resulting in the repeated creation of policies without a theoretical underpinning of race that are doomed to eventual failure. A recent 2022 report by the Illinois CPA Society highlights the severity of the problem, as 70% of past under-represented minority (URM) alums of its Mary T. Washington Wylie Internship Preparation Program, designed to promote diverse career success in the profession, reported seeing the profession as not or just somewhat diverse. [URM refers to Black, Hispanic/LatinX, and Native American people, who continue to endure the proliferation of acronyms, including Black, Indigenous, and other people of color (BIPOC), people of color (POC), and historically underrep-resented group (HUG).] A further 36% felt that accounting was not inclusive. As one alum stated:

No one looks like me … it was shocking to realize there’s not one Black female partner in the practice. The lack of representation makes it hard to want to stay. (K. Natale, A CPA Diversity Report: Uncovering the barriers to success, 2022, pp. 12, https://tinyurl.com/5n92ekha)

The report continues to state that the lack of racial difference led many URM alums to ask themselves if they really belonged in the profession. Thus, these racialized Others were unable to contort themselves to the pervasive whiteness of the profession, characterized by the pale and male norms and values that have always dominated ideas of professionalism, forcing them to be isolated and alone. The all-consuming whiteness of accounting, which is a function of the profession’s status quo, produces unassailable systemic barriers that often stall career progression while effectively preventing prospective diverse students from entering the profession. Given its declining numbers, the profession can ill afford to ignore this situation.

Pieces of the Puzzle

To foster consequential change, the authors believe that multiple pieces of the puzzle must be addressed simultaneously, the first of which begins with the messaging that prospective students receive about what an accounting career can be, while making clear the salience of racial practice to the profession. An honest approach—yet to be attempted for fear of brand damage to accounting’s advertised meritocratic stance (A. Lewis, ‘Counting Black and White Beans’: Critical Race Theory in Accounting: Emerald Group Publishing, 2020)—would start with the AICPA’s 2021 data showing a minimal representation of 2% Black CPAs and partners (AICPA, 2021 Trends Report, https://www.nysscpa.org/2021-trends). This transformation must then be carried through to the accounting classroom and into professional practice to racially transform the accounting institution at the structural level. In all, we believe the profession and academy must move away from initiatives that foster inclusion and representation and move towards strategies that foster specific anti-racist transformation (I. X. Kendi, How to be an Antiracist, One world, 2019).

Transform the Messaging

Perhaps most troubling messaging is the implicit assumption of the “dullness” of the profession by society as a whole and younger generations in particular. The adage of the dull, green visor–wearing bean counter has seen a precipitous fall in students enrolled in accounting majors compared to previous years (I. Jeacle, “Beyond the Boring Grey: The Construction of the Colourful Accountant,” Critical Perspectives on Accounting, vol. 19, 2008, pp. 1296–1320). This trope is bolstered by social media, which tells prospective students and professionals that a career in public accounting is miserable. For example, a widely known social media account, TheBig4Accountant, currently boasts 665,000 followers who share personal experiences in the profession. The message conveyed is that firms will work you to death with minimal pay increases, there is little long-term career pay-off for the majority of new hires, and the work is mundane and boring. This messaging holds more weight in the minds of younger generations than any firm messaging ever could—messaging that has, in large part in our opinion, led to the current decline in the accounting pipeline.

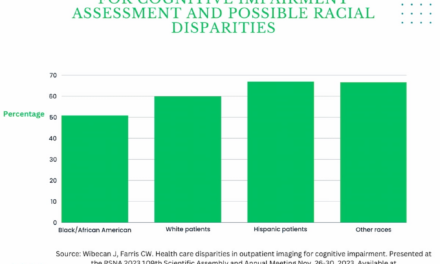

The numbers are startling. The 2019 AICPA Trends Report highlighted that a 4% fall in enrollment in bachelor accounting degree programs had occurred from the 2015/16 to 2017/18 academic years. Worse, some programs reported a precipitous 34% decline in enrollment in intermediate accounting courses between 2015/16 and 2018/19 (https://www.nysscpa.org/2019-trends). When factoring in diversity, matters get worse still: in 2017/18 accounting program enrollees classed as Black or African American were only 10%, compared to 56% white. At the master’s level, the negative trend continued: Black enrollees were only 7%, compared to 53% white (Lewis, 2020). Matters of the environment, anti-racism, and social justice are what this current generation cares most about and should be reflected in the curriculum, as well as overarching societal attitudes that these matters are key to accounting and the work it does. Fostering this passion and interest will then fuel increasing numbers of not just dominant majority white students, but also that of URM students as well (ACCA, Groundbreakers: Gen Z and the Future of Accountancy, 2020a, https://tinyurl.com/y3py7rnv).

Transforming this messaging would also require universities to shift their focus away from traditional public accounting roles. Narrowly focusing on tax and audit roles does not take into account the fact that a growing majority of students want to do work that more directly impacts society in positive ways, and it does not allow URM students to see themselves in the roles presented. Instead, we can strive to introduce a broader perspective of the work accountants can do. For example, with the help of forensic accountants from Grant Thornton, a report uncovering the ties between the Church of England and the transatlantic slave trade was recently released, leading the church to set aside 100 million pounds to right “past wrongs” (Church Commissioners’ Research into Historic Links to Transatlantic Chattel Slavery, https://tinyurl.com/39cn94hu). Work such as this is rarely highlighted—nor is the fact that accounting was a key technology that enabled the subjugation of African bodies through bookkeeping valuations of human assets. Yet it is just this kind of work that could shift the perspective of the large number of URM students who believe that a career in accounting offers them little opportunity to positively impact their community and society (K. James, “Achieving a more diverse profession.” The CPA Journal, vol. 76, no. 11, pp. 62–65, 2006). This would also highlight the power of accounting to establish systems of accountability and raise awareness of how accounting practice can be integral to the creation and perpetuation of human rights atrocities. A far cry from the traditional stereotypes ascribed to accountants.

Transforming this messaging can start long before prospective students enter college. The profession can do a better job of constructing the idea of an accounting career and increasing the financial literacy of high school students through programs that already exist. For example, Junior Achievement defines itself as the world’s largest organization dedicated to educating students in grades K-12 about entrepreneurship, work readiness, and financial literacy through experiential, hands-on programs. Similarly, the Accounting Career Awareness Program (ACAP, https://nabainc.net/acap/), which has been run for a little under half a century by the National Association of Black Accountants (NABA), is designed to enhance the awareness of accounting and business career opportunities among URM high school students. Programs such as these expose high school students to introductory accounting, finance, economics, and management through innovative sessions by college faculty and guest lecturers. Firms and universities are waking up to the benefits of partnering with programs like these to reach high school students that might never consider a career in accounting otherwise. One example is the KPMG foundation’s funding of LaGuardia Community College’s summer bridge program, Career Start 2.0, which offers concentrated math instruction and directed career exploration to prepare students for admission to one of their degree programs (A. Whitehead, “KPMG U.S. Foundation Announces Reaching New Heights Program Grant Recipients,” 2023, https://tinyurl.com/2etp7w2v.). Such initiatives also fill the need of increasing the financial literacy of racially diverse high school students, something that they may not get at home.

Another program, designed for first- or second-year college students who have not quite decided if accounting is for them, is the annual Mary T. Washington Wylie internship preparation program, sponsored by the Illinois Certified Public Accountants Society (ICPAS). This award-winning program was designed to propel racial and ethnic minority college students into the accounting profession. (Mary T. Washington Wylie was the first Black woman CPA in the United States; she began her own accounting practice in the basement of her Chicago home.) The program introduces students to various resources such as training and mentorship. Participants then have the opportunity to interview with different accounting firms and learn about other educational prospects; several participants credit the program with transforming their future.

Lastly, universities and public accounting firms can push publishers to ensure textbooks are representative of a more diverse population (A. Duff, “Big Four Accounting Firms’ Annual Reviews: A Photo Analysis of gender and Race Portrayals,” Critical Perspectives on Accounting, vol. 22, pp. 20–38, 2011; O. Kyriacou, “Accounting for images of ‘equality’ in digital space: Towards an exploration of the Greek Accounting Professional Institute,” Critical Perspectives on Accounting, vol. 35, pp. 35–57, 2016). A quick glance at any introductory accounting textbook implies that only a narrow, “pale and male” demographic belongs in the profession. This imagery does not align well with the AICPA’s push for greater diversity, nor the efforts being made by larger firms in this regard (“AICPA is Committed to Equity: Our Statement,” 2020, https://tinyurl.com/yb3t9jkm; KPMG, The Future is Inclusive,” 2018, https://tinyurl.com/53cxrb5c). Current textbooks often display images of notable white business leaders (e.g., Warren Buffett, Elon Musk), while the notable Black/African American business leaders are conspicuous by their absence, instead represented by Black leaders in athletics and music (e.g., LeBron James, Drake), denoting the hidden but powerful stereotypical message that these are the only arenas of authentic Black success. This is partially due to the narrow demographics of textbook authors (C. Alston, L. Flint, and S. Manley, “A Content Analysis of the Portrayal of Under-Represented Minorities in Introductory Accounting Textbooks,” Forthcoming, 2023).

Transform the Classroom

Providing an alternative vision of what it means to be an accountant and who belongs in the profession can only go so far. A concurrent transformation of pedagogy and curriculum would also be necessary to maintain students’ interest, ensuring a larger percentage of URMs matriculate through the accounting program and join the profession. For example, a lot of students lose interest in accounting when they enter their introductory accounting class and are immediately confronted with the technical intricacies of accounting. Rather than jumping straight into debits/credits, there could be a true introductory class that focuses on accounting theory and introduces students to the role accountants play within society. Introducing students to the multitude of ways in which accountants aid in the construction of reality could provide a stronger foundational interest in the profession than technical jargon does (R. D. Hines, “Financial Accounting Knowledge, Conceptual Framework Projects and the Social Construction of the Accounting Profession,” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, vol. 2, no. 2, 1989). This would be a key area of interest convergence, a concept conceived by legal scholar Derrick Bell, which suggests that minority Black success is only supported when it converges with majority white self-interest (Silent Covenants. Brown v. Board of Education and the Unfulfilled Hopes for Racial Reform, Oxford University Press, 2004). In short, a radical rethinking of how and what counts as authentic accounting knowledge might reverse the anti-accounting trend prevalent amongst both white and URM students.

Antiracist transformation can also be accomplished through the way professors approach the classroom and pedagogical practices. A central component of maintaining our current system of racial oppression within the accounting academy and profession lies in a collective unwillingness to critique power; Who holds it, who wields it, who is harmed by it, and how the practice of accounting can be complicit in all of it. Fortunately, accounting is a social science that lends itself to critical dialogue between teacher and student, so that all parties involved can raise collective consciousness regarding racial structural oppression (among others) and work together to envision a new way forward. This requires, however, that educators have honest conversations about racism, sexism, and the like. This would lay the foundation to move towards what is referred to as accountability-based accounting (J. Dillard and E. Vinnari, “Critical dialogical accountability: From Accounting-Based Accountability to Accountability-Based Accounting,” Critical Perspectives on Accounting, vol. 62, pp. 16–38, 2019).

It is also important to note that the lack of representation and belonging starts in the accounting classroom. The paucity of Black accounting professors in U.S. business schools is environmentally microaggressive in nature, implicitly conveying to accounting students of color that they do not really belong in the program or industry they wish to join, because they do not see fellow students of color nor URM professors to challenge this perception (H. Brown-Liburd and J. R. Joe, “Research Initiatives In Accounting Education: Toward a More Inclusive Accounting Academy,” Issues in Accounting Education, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 87–110, 2020). As of 2020, there were only 211 Black accounting professors in the whole of the United States. This level of representation is largely due to the PhD project that was founded in 1994 and funded by KPMG, “with the goal of diversifying corporate America by diversifying the role models in front of the classrooms” (The PhD Project, “Success by the Numbers,” 2018, https://phdproject.org/about-us/). Programs such as this should be protected and replicated by other firms.

In short, critically educating the future minds of business can transform the future world of business. Approaching the classroom with a posture of business as usual will only reproduce institutionally racist structures and maintain the profit-over-people mentality that serves only a few while harming the majority, especially those that sit at the intersection of multiple compounding systems of oppression. Employing new pedagogical techniques, as well as shifting paradigms in the classroom to be more human-centered rather than profit-centered, is a necessary step in the progress towards racial equity.

Transform Institutional Practices

The last and, in this author’s opinion, most important piece of the puzzle is transforming the institutional practices within public accounting firms. Increasing the representation of URMs in the classroom and profession only goes so far. Without structurally transforming the professional practices that maintain the dominance of whiteness in the profession, as documented by several studies over recent years, minimal or declining retention will continue, leaving the profession worse off than it is now (P. L. Davis, D. Dickins, J. L. Higgs, and J. Reid, “Auditing While Black: Revealing Microaggressions Faced by Black Professionals in Public Accounting,” Current Issues in Auditing, 2021; L. Rukasuwan, “Examining the career progression of Black public accountants: A social identity approach and redesigned system of exclusion in the U.S.,” doctoral dissertation, Texas Tech University, 2022; Lewis, 2020).

Professional standards and norms are a product of historical construction, so it should be no surprise then that the accounting profession is defined by whiteness. In this sense, professional standards are largely representative of ideas of respectability that have served to keep certain populations down and out and required assimilation of any racially or ethnically diverse individuals who gain entrance. These standards highlight acceptable ways to speak and dress, and even informs what food is acceptable to eat in the employee break room. The fact that whiteness is the acceptable default places the responsibility squarely on the shoulders of URMs to assimilate to what Nneka Logan termed the white leader prototype (“The White Leader Prototype: A Critical Analysis of race in Public Relations,” Journal of Public Relations Research, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 442–457, 2011). More specifically, Rukasuwan (2022) found that Black public accountants feel constant pressure to alter their speech and physical appearance, a kind of self-censoring that exacts a heavy psychological toll. It is the essence of having to engage in “Working Identity,” which is to mold what a raced and gendered professional is into a recognized white professional norm, so as to be accepted by the profession as genuine and therefore able to succeed (D. Carbado and M. Gulati, “Acting White. Rethinking Race In “Post-Racial” America,” Oxford University Press, 2013). This pressure, along with having to deal with racial microaggressions on a daily basis and a lack of career sponsorship, has been a key factor in Black accountants deciding to leave their firm or practice altogether.

It is important to note, however, that deconstructing these norms and standards is not work that only white accountants and academics need to undertake. As noted above, white supremacy doesn’t need white bodies to survive, just warm bodies who are willing to uphold and enforce its values. Therefore, everyone must do the work to deconstruct the values of whiteness that have been conditioned since childhood to be seen as the default. For example, at the associate level of the largest firms, the second most represented racial group behind whites is Asians. This group has faced a peculiar kind of socialization in the form of the “model minority” stereotype that has been used as a hegemonic device “that serves as a wedge between Asian Americans and other groups of people of color” (S.J. Lee, “Unraveling the ‘Model Minority’ Stereotype: Listening to Asian American Youth,” Teachers College Press, p. 120, 2015). Deconstructing and redefining what it means to be professional, what it means to be an accountant, is work that is personal and unique for each individual and racial group.

Outside of the day-to-day institutional practices that shape the experiences of URM accountants there is also minimal and inconsistent reporting on firm demographics, which suggests a lack of commitment to racial equity. In their transparency reports published following the racial reckoning of 2020, all of the Big Four stated that they would benchmark their performance—but in the opinion of the authors, this to our mind hasn’t been done in any sustained and explicit manner. Specific regular diversity metrics are still needed so that the profession can have targets and measures for outcomes, along with a commitment to meet those goals.

The Larger Pipeline and Retention Issue

As mentioned earlier, addressing the issue of racial equity in the profession speaks to the larger pipeline and retention crisis the profession is currently facing. Across the country, universities are experiencing decreasing enrollment and state CPA societies cite declining CPA exam candidates (Natale, 2022). In September 2020, the Illinois CPA Society launched a survey targeting accounting students, graduates, and professionals under age 35, both CPAs and non-CPAs. It’s notable that 51% of respondents did not plan to obtain the credential, the top reasons being “not seeing the value relevance to their careers, not seeing the return on investment, employers do not require or support it, and other credentials or specialties are more valuable to their careers.”

In 2019, Howard University’s Center for Accounting Education (CAE) collaborated with members of public accounting firms, professional accounting associations, state CPA societies, and accounting academics to advance the discussion of career conditions for Black accounting professionals (R.M. Dey, L. Lim, F. Ross, T. Walker, and K. Bouyer, “Greater Than the Sum of its Parts: Collaborating for Diversity,” Current Issues in Auditing, vol. 16, no. 1, A9–A17, 2022). CAE began by comparing a survey of Black accounting professionals in 2006 to 2017, noting that while public accounting firms have introduced several diversity and inclusion initiatives in response to disparities, “Black accountants’ recruitment, career advancement, and retention significantly lags their non-Black peers in public accounting firms” (AICPA, 2019 Trends, https://www.nysscpa.org/2019-trends). The collaborative body presented recommendations shared with the CEOs of the largest accounting firms; while these appear to be well intentioned goals, they lack clearly identified quantitative metrics that can be periodically measured going forward.

KPMG, at least, seems to have heard this call for more transparency and has responded to the pipeline and diversity issue by increasing scholarship awards to URM students and introducing their Accelerate 2025 initiative (https://tinyurl.com/2hb6dvth). Of important note is their goal of doubling the representation of Black accounts in partner and managing director roles; this points to the issue with previous goals of increasing representation of underrepresented groups in general, as most of those gains were accrued to white women. Continuing to include this group in measures of diversity, without specifically defining goals for other racial and ethnic groups, can stifle the transparency that firms are attempting to create.

These efforts also don’t acknowledge the fact that the “Great Resignation” affected a wide range of industries, revealing a larger issue with how society values work and working people. As labor movements have raised collective consciousness, accounting graduates and junior associates are paying attention and becoming critical of the exploitative labor practices of large public accounting firms, sparking discussions of unionization. Add to that the fact that cost of living has consistently outpaced wages, and a public accounting career no longer represents a clear path to class mobility like it once did.

More and more, it is becoming necessary to have a side hustle in order to experience the economic “freedom” that older generations could gain from joining the accounting profession. A fact that is made clear in online forums such as Reddit where public accountants from the staff level all the way to partner share stories and salaries openly. To address this issue, the profession must critically reflect on how human capital and work is valued.

Making this shift would challenge the traditional hourly based billing that firms employ in favor of a system of value-based billing similar to what law firms have begun adopting in recent years. Work is priced according to the outcome rather than the input, creating more space for work-life balance (Deloitte, “Value-Based Pricing: Aligning Cost and Value of Legal Services,” https://tinyurl.com/47hcmrzr; 2021). What an accounting job pays matters to URMs, who often begin from a lower socio-economic base. If becoming a CPA is expensive, if doing the work is all consuming, then by definition promising accountants of color will not enter the profession, or stay if already here. Neither will their white counterparts, because both will judge the profession as unable to value them—even when it purports to do so.

Doing the Work

It is our belief that the profession and academy have a lot of work to do—one, to change the minds of younger generations when it comes to a career in accounting; two, to change the everyday practices that shape the lived experiences of racially and ethnically diverse accountants. Without addressing each piece of the puzzle outlined here, the profession will inevitably struggle to find individuals willing to do the work, white and Black alike. Prospective students and junior accountants of all backgrounds are demanding structural change to address the ever-increasing inequality and injustices throughout our society. The profession cannot afford to sit by and not practice what it preaches. Continuing to talk about increasing diverse representation while maintaining professional standards informed by whiteness is no longer good enough. Anti-racist transformation—in the classroom and in practice—is the only way forward.