African Americans have made some significant contributions to the history of American sports, achieving many firsts across various disciplines often while breaking various social barriers.

Fritz Pollard became the first African American to play in the NFL in 1920; Joe Louis became the world heavyweight boxing champion in 1937; Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1974; Althea Gibson broke the racial barriers in international tennis in 1950; and in 1957, Darlene Anderson became the first African American woman to play professional Roller Derby.

Born in 1939 in Pasadena, California, Darlene was one of five siblings, with three of those siblings being her older brothers. While we realize that it might sound stereotypical, growing up with three older brothers who probably wrestled, fought, and competed amongst themselves most likely stacked on top of Darlene’s innate athleticism, resulting in her becoming an excellent athlete comfortable with any athletic endeavor, even at a relatively young age. She always played sports.

However, while her mother was against Darlene playing any “rough sports,” her father was more lenient, often taking a “just don’t tell Mom” approach to any of those sports Darlene felt inclined to play. After her mother forbade her from playing baseball, perceiving the sport as “too rough,” Darlene convinced her parents to let her try skating, leading her mother to think she took up ice skating as something more suitable for young ladies. Her parents would even drop her off at a local Roller Derby center, believing it was an ice rink — and Darlene thought it best not to correct them.

In fact, Darlene and her friend Joanne hatched a plan in which Darlene would regularly spend the night at Joanne’s house on Friday so the two could take several buses and trolleys from Pasadena to Los Angeles on Saturday morning to get to practice. After four hours of practice, they would go to the Olympic Auditorium to watch the games. This lasted for about eight months. Nobody thought of questioning Darlene about her whereabouts, as she always returned home on time.

All that came to an end when her coach encouraged her to compete in time trials in one of the professional games at the Olympic Auditorium after just eight months of weekly practices. Darlene had no intention of joining a team; she was simply encouraged by the coach and friends to attend the event. According to her own account, it never dawned on her that she was trying out for a team; all she wanted to do was skate at the Olympic Auditorium. So, she did. She proved to be a great skater, and when the time trials ended, they announced her as the winner.

Her performance was so fantastic that she ended up being the Brooklyn Red Devils’ first pick of two. Taken aback by their decision and thinking only about catching the last bus home, Darlene heard her name being called, but she just got up and left the auditorium. On the way home, coming to terms with what just happened, Darlene also realized that she had to come clean with her parents. It was 1956 and she was still a minor, which meant that she would have to get their permission to travel with the rest of the Roller Derby team. She had to let her parents in on the secret of her training.

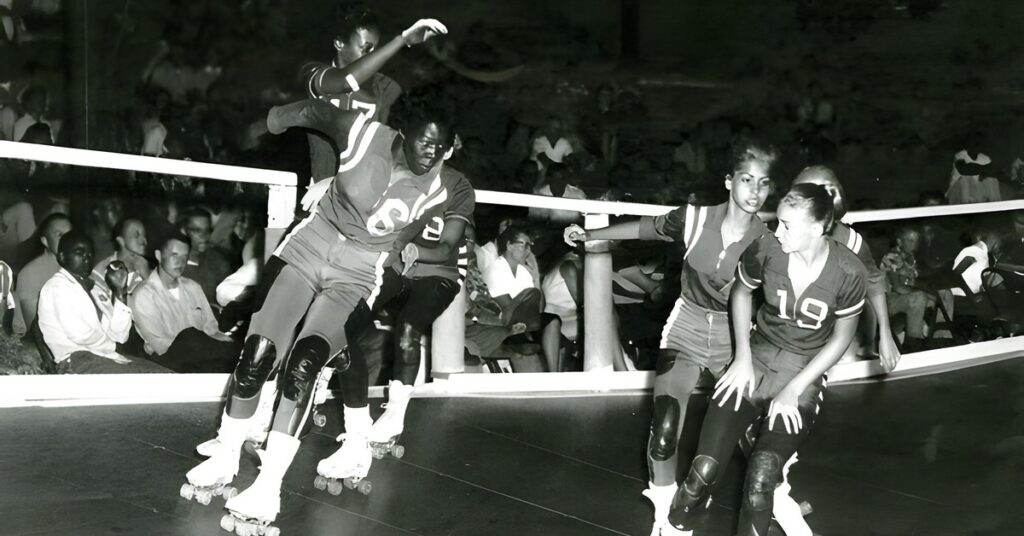

Darlene knew her mother wouldn’t approve, but she relied on her father’s leniency and the fact that he might just side with her — and she was right. In 1957, she officially became a member of the Brooklyn Red Devils, also becoming the first African American woman to play Roller Derby in a professional capacity. Please note that the 1950s were a time when segregation was still deeply entrenched in American society, and Roller Derby, a sport that gained immense popularity during this era, sadly still reflected that.

Darlene’s entry into the predominantly white and segregated Roller Derby scene was met with resistance. She faced numerous challenges, from racial prejudice to skepticism about her abilities. Though her team treated her as their equal in all aspects and she traveled with them everywhere, Darlene could not attend any sports events that took place in the South. So, while she felt safe and comfortable amongst her teammates, both segregation and racism were still a real threat to Darlene. She would be sent home while the team traveled through the South.

At the time, as most young adults do, she thought it was because she wasn’t a good enough player. However, with age comes experience, and she later realized her teammates knew she wouldn’t be able to eat or live with them during any events held in the South and that, even though she didn’t register it at the time, they were looking out for her and trying to keep her safe. However, despite hardships, her remarkable talent and unwavering determination gave birth to a fantastic career, and Darlene became a force to be reckoned with on the tracks.

In 1959, Darlene Anderson was crowned Rookie of the Year. She went on to play for several teams over the years. She eventually retired in her early 30s, but not before leaving a lasting impact on the world of Roller Derby. After she retired, Darlene worked as a clerk, becoming the first African American woman to be a parimutuel clerk with the Southern California Racing Association, breaking yet another barrier.

From training in secrecy to her induction to the Roller Derby Hall of Fame, Darlene Anderson challenged the prevailing stereotypes about Black women and their place in the world of competitive roller derby.