Douglas Melville’s book, Invisible Generals: Rediscovering Family Legacy, and a Quest to Honor America’s First Black Generals, is, in part, defining in its title. Four generations ago in his family leads Melville to America’s first Black general, Benjamin Oliver Davis, Sr. Three generations back? His great-uncle Benjamin Oliver Davis, Jr.—American second Black general. The inspiration for Melville, beyond the trailblazing progenitors who “utilized systems designed to hold them back” was he went and saw the film Red Tails. The dramatization about the Tuskegee Airmen left Melville shocked—his great-uncle had been scrubbed from the narrative. This essentially is the inciting incident for Melville to begin his journey in restorative history work regarding his military family members. Kirkus writes of Invisible Generals, “Melville traces the travails his ancestors faced while building records of excellence in a military that, it often appeared, only grudgingly accepted them. Moreover, he recounts his own efforts to be sure they are properly recognized and honored. ‘I can see how the quest never ends,’ Melville writes, and one aspect of that quest is for his military ancestors to be thought of as they wished: Americans, period.”

It just so happens I have found myself encountering several texts and installations on this subject. I recently read Chad L. Williams’ The Wounded World: W.E.B. Du Bois and the First World War, and, some months ago, Steven Dunn’s excellent water & power based in part on Dunn’s experiences in the Navy. This fall I paid a visit the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which has an extensive exhibit on the long legacy of Black people fighting for the U.S. military. (It goes back further than you think.) While all, along with Melville’s book, were powerful examples of the complicated and often downright fraught history of Black military service for a racist country, one letter from Williams’ text stuck with me most. It was penned by William Hewlett to Du Bois during World War I, just before the soldier’s return home. Hewlett writes:

If democracy in the United States means—disfranchisement; jimcrowism; lynch-law; biased judges; and juries; segregation; taxation without representation; and no representatives in any of the law making bodies of the United States; if that is the White American of true democracy—Then why did we fight Germany; why did we frown [on] her autocracy; why did black men die here in France 3300 miles from their homes—Was it to make democracy safe for white people in America—with the black race left out.

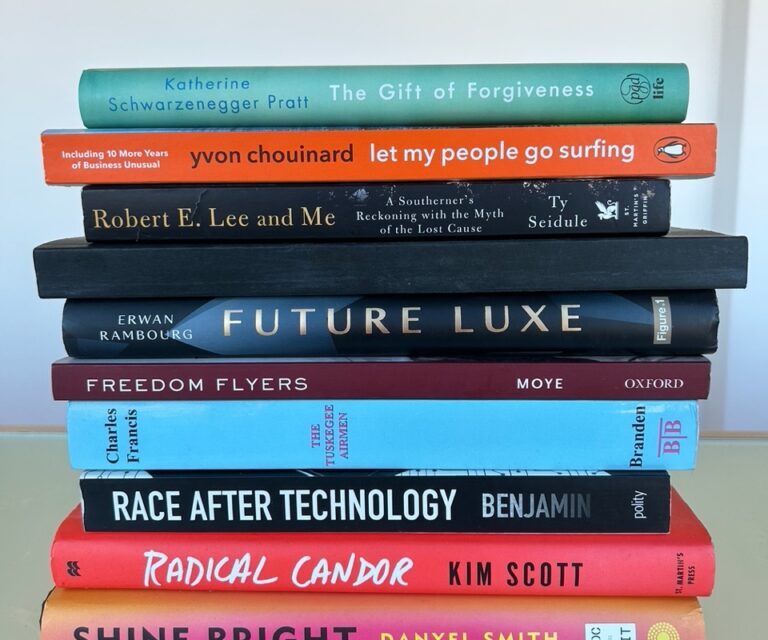

Melville tells us about his to-read pile, “My nightstand pile is an intersection between inspiration, personal growth, the past, the future and business. I have a habit that I call ‘checklisting’ where I let my mind wander and write down the words, thoughts and subjects that come up. This practice inspires the subjects for my reading habits. Being a diverse author, I like to read, and re-read a wide range of perspectives and hear a variety of voices to ensure I’m open minded and fine-tuned personally and professionally. For me, it’s important to either wake up or go to bed—with daily thoughts that help set my dreams and my reality.”

*

Todd Moye, Freedom Flyers: The Tuskegee Airmen of World War II

In its review, Publishers Weekly writes of Moye’s book, “Despite official skepticism and occasional hostility, the Tuskegee Airmen successfully demonstrated ‘that racial segregation of troops was inefficient and… hindered national defense.’ Their record helped persuade the air force—largely for ‘reasons of operational self-interest’—and President Harry Truman to seek the immediate desegregation of the military after the war. The author directed the National Park Service’s Tuskegee Airmen Oral History Project and mined some 800 interviews for his exhaustive research. Moye’s lively prose and the intimate details of the personal narratives yield an accessible scholarly history that also succeeds as vivid social history.”

Charles Francis, The Tuskegee Airmen: The Men Who Changed a Nation

As Melville’s book attends to the Tuskegee Airmen, it’s not a surprise we see a few books on the historical group. In World War I, Black men hoped to act as aerial observers (no ammunition), but were denied because of their race. One went as so far to serve for France air force during that time as his own country rejected him. It wasn’t until World War II that Black men were able to fly, albeit in segregated units. The Army Air Corps (now US Army Air Force) created remarkable restrictions for what allowed them to select potential Black pilots, believing there would hardly be enough to scratch together a squadron. Unbeknownst to them, many went through the government-sponsored Civilian Pilot Training Program (specifically made in order to help bolster military numbers in the war). By 1941, the 99th Pursuit Squadron was the first all-Black flying unit in the United States.

Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code

Rachel Boccio, in her review of Benjamin’s book in Configurations, writes, “That digital code—the interminable combination of binary numbers underwriting our high-tech age—can be apolitical, unbiased, and colorblind is a techno-utopic fantasy undercut by decades of data-driven and encrypted inequities. In Race After Technology, Ruha Benjamin analyzes the mechanisms behind a digital caste system that she calls the ‘New Jim Code’: the reproduction of historical forms of discrimination by modern technologies that are perceived and promoted as objective or progressive. Benjamin considers the ambitions and methods of a wide range of programmers and initiatives, including some with democratic aims. And yet, as she argues, even ‘technical fixes’ to systemic inequalities in housing, education, healthcare, and policing lead, very often, to more insidious forms of racism, insidious in that the perpetrated wrongs become harder to recognize.”

Kim Scott, Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity

Erin Vanderhoof, in her Vice review of Scott’s book, writes, “With little hierarchy, institutional memory, or bureaucracy beyond ideas, start-ups begin their lives in disarray. Anybody who has seen The Social Network can tell you that, and Scott affirms this stereotype when she mentions that she was generally older than her managers at Google and Apple. She seemed to be the person you called when you needed an adult in the room.” Vanderhoof goes on to say, “[Scott] assumes that everyone who isn’t good at overseeing a schedule, working with others, setting priorities, and managing workflows never becomes a boss. Anyone who works in the real, mediocre world knows that is not the case. In Silicon Valley, your ability to be a founder is based entirely on your ability to have an idea, convince investors to give you money, and attract media attention. None of these qualities ensures that you will be even a passable manager.”

Danyel Smith, Shine Bright: A Very Personal History of Black Women in Pop

In her book, Smith attends to the known and not-so-known great singers such as Cissy Houston, Sister Rosetta Sharpe, Janet Jackson, and many others. Smith’s book received a starred review in Library Journal, where Lisa Henry writes, “This book is the culmination of years of interviews, research, and personal appreciation for the music that shaped the author’s own life. Smith explores famous musicians as well as those who may have been forgotten… Smith interweaves heartfelt stories of her own life as she provides evidence of the continual erasure of Black women’s contributions to the evolving music industry, even as they upended all cultural norms and created unprecedented sounds.”

Katherine Schwarzenegger Pratt, The Gift of Forgiveness: Inspiring Stories from Those Who Have Overcome the Unforgivable

Schwarzenegger Pratt interviews a series of famously wronged people including Elizabeth Smart, who Margaret Talbot describes as “a member of a tiny sorority of women who have escaped from modern-day Bluebeards and shared their stories.” There is also Sarah Klein, who on her law firm’s page is profiled as “an advocate for victims of sexual abuse, and a former competitive gymnast. Sarah is also one of the first known victims of former Olympic Women’s Gymnastics Larry Nassar, and in July 2018, at the ESPYs, Sarah accepted the Arthur Ashe Courage Award on behalf of herself and the hundreds of other survivors of Nassar’s sexual abuse.” And, also, Sebastián Marroquín who, Paul Imson explains, “At just 17, Mr. Marroquin, who changed his name from Juan Pablo Escobar, was effectively heir to the largest drug trafficking empire in history.” In short, all the people interviewed have had remarkably horrible things done to them by specific people and who, as survivors, have written about it and/or do lectures. Some, it seems, are more successful than others.

Yvon Chouinard, Let My People Go Surfing: The Education of a Reluctant Businessman

Chouinard reentered more American minds recently when he announced in 2022 that his family’s company Patagonia, worth $3 billion at the time, was put into a trust so that the entirety of its $100 million annual profits go toward fighting climate change. This isn’t the first time Chouinard or Patagonia engaged in serious activism, but it certainly raised its fair share of money-havers’ eyebrows. Chouinard was famously a climber who ended up wildly wealthy—and apparently uneasily so—as the subtitle of this memoir tells us—because of the success of his business. What got Chouinard into rock climbing was actually his love falconry as a youngster and his desire to find falcon nests. He eventually started to make his own climbing equipment, teaching himself how to so, then starting a company specializing in climbing gear. Check out this amazing photo of him on Mt. Hood in 1975. It’s clear from the start Chouinard’s activism was part of his approach from the start. In 1970, he discovered the pitons he sold—and comprised 70% of his income!—was harming Yosemite. He and his business partner created new tools and advocated for “clean climbing” to avoid further destruction in Yosemite and elsewhere.

Ty Seidule, Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause

In John Reeves’ review of this book in the Washington Post, he writes, “Seidule tells the story of his transformation from a believer in the Lost Cause to a critic. Growing up in Virginia and Georgia, he worshiped Lee. It was only later, as the head of the history department at the U.S. Military Academy, that he discovered the truth about Confederate myths. Seidule writes: ‘I grew up with a lie, a series of lies. Now, as a historian and a retired U.S. Army officer, I must do my best to tell the truth about the Civil War, and the best way to do that is to show my own dangerous history.’ Seidule has written a vital account of the destructiveness of the Lost Cause ideology throughout American history. He shows how films, textbooks and memorials promoted white supremacy by glorifying traitors and enslavers like Lee and other Confederate leaders.”

Rob Schwartz, 52 Fridays

Melville explains this one: “One of the books—the all-black spine fourth from the top—is titled 52 Fridays. It’s an independent book written by Rob Schwartz, 2016. Upon becoming CEO of Madison Ave Agency TBWAChiatDay NY in January 2015…each week he wrote a sometimes funny, sometimes inspirational, often quirky creative email to keep the week, advertising and our culture in perspective.”

Erwan Rambourg, Future Luxe: What’s Ahead for the Business of Luxury

“Luxury” is a word we have in English, like so many, from French because of the Norman Invasion. In Old French, luxurie meant “debauchery, dissoluteness, lust.” So, in the 13th century, in Middle English, luxure or luxurye specifically described sex. By the mid-14th century, it became “lasciviousness, sinful self-indulgence.” It is derived from the Latin lūxus, or excess—this derives from luctari (“to struggle”). In the OED, it states “In Lat. and in the Rom. langs. the word connotes vicious indulgence.” It didn’t become the word we think of today until the 1700s.