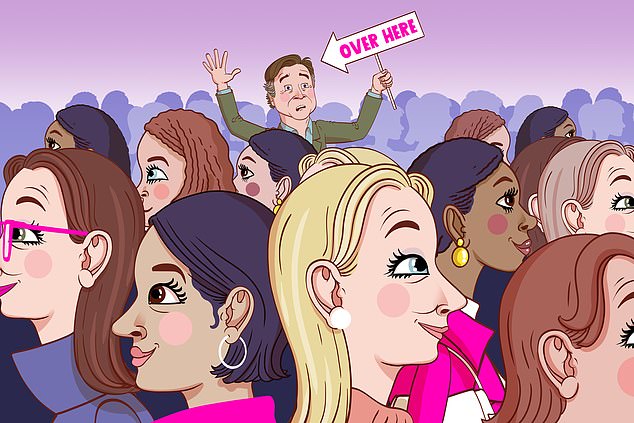

Middle-aged women often complain that they have become invisible, mainly to men of a similar age who only look at younger women. They are right.

Obviously men in their 50s and 60s are not hugely interested in women of the same age, because these men still regard themselves as about 40 on a good day, even if those good days come round less and less frequently.

But what the women of a certain age may not realise is that the younger women are not actually looking back at the older men, because those men, too, have become invisible.

Even if we have kept in reasonable shape — which terrifyingly few of us have done — these younger women are simply no longer interested in us.

At 62, if you’re really lucky they’ll let you buy them dinner. But that’s all you’re getting. We have joined the vast ranks of the unseen.

The invisibility factor applies equally to those of us in long-term relationships as well as those who are not. A quick straw poll of my friends and contemporaries confirms my assumption that none of us are getting any sex at all, either with our wives or with anyone else.

The only ones who are getting any are those previously chucked out by their wives for some poor behaviour, who now find themselves in a new relationship with a younger woman.

Their gratitude is obviously unbounded, as mine would be if something similar ever happened to me. This woman actually wants to sleep with me? Is she entirely sure about that?

The maximum negotiable age-gap appears to be about 20 years, so at 60 we might still be attractive to women in their early 40s, especially those with poor eyesight.

Fifty-year-old women will take a man of 70, and 60-year-olds will go up to 80, although there she might start to think of herself less as a lover than a live-in carer.

I know a woman who started going out with her husband when she was 25 and he was a young buck of no more than 50. She is now in her 60s and he has just turned 90.

She says she still loves him, but I doubt that their house is a hotbed of carnal excess. Unless she is knocking off her personal trainer, and to be honest I wouldn’t blame her if she was.

Remember that it is one thing to fancy the young, free and single; it is entirely another to be fancied back. They may find your money captivating, if you have any, and they may be impressed by your worldly air, your immeasurable experience of life and those distinguished-looking alcoholic red patches on your cheeks.

But no young woman has ever said the words ‘I love all that hair growing out of your ears’ or ‘How do you get your eyebrows so bushy?’ Unfortunately, although our bodies may be 60 and above, our minds are about 17. We are the new incels (involuntary celibates), a term previously applied only to the young men who become radicalised misogynists because girls of the same age won’t give them the time of day.

Don’t blame the girls, who are all eyeing up men of a few years older, or at least the ones who haven’t grown appalling beards. But they are not eyeing up you and me, which is our tragedy, unless we are hugely rich and/or narcissistic alpha males.

When I was young, I used to hate the older men who had their pick of the younger women I knew. I still do, although their equivalents now are years and years younger than me.

(In 2020, the Hollywood actor Dennis Quaid married a woman 39 years younger than him. Someone on Twitter did the sums. ‘His first wife was three years older than he was. His second wife (Meg Ryan) was ten years younger. His third wife was 20 years younger. His fourth wife will be 40 years younger. Dennis Quaid’s fifth wife hasn’t been born yet.’)

Eventually, as my mother has confirmed, everyone is younger than you. Everyone left, that is. And by then, you’re more invisible than you could ever imagine.

Unfortunately, it is in the nature of some men — and I am one of them — to suffer enormous crushes on women who are entirely unattainable: either they are 400 years younger than you, or they have a boyfriend who represents his country at taekwondo.

It seems to be getting worse as I get older, not better, and as it gets worse the chance you can do something about it recedes into the distance, like your health and your hair.

I occasionally get looks from older women, often in their 60s or 70s, whose husbands may have died, or walled themselves up in their sheds, but who still have some snap in their celery.

These looks often have an undercurrent of visits to National Trust properties and their attendant tea-rooms, where knees could possibly be fondled.

As you can see, I may not have an actual sex life, but I have an unusually rich imaginative sex life, as do many of my male friends. It’s a consolation, if a very, very small one.

Several female friends have reported fallings-off of their libidos, with one or two expressing deep satisfaction that they are ‘past all that now’. God, if only.

Actually, I would miss it if it were gone, as it dominates my life to an unhealthy extent. I am someone who can fall in love three times walking to the off-licence, and three more times walking home again. It’s exhausting but not unenjoyable.

I have often wondered about libido: how much is in the mind and how much is in the sweaty groin area? How much is a relationship about sex anyway?

Given how many couples I know stopped doing it years ago, I would say very little. Few couples seem to stay together for the sex, and those who do (and seem to talk about it endlessly) are just annoying.

Instead, people talk self-importantly about ‘companionship’. Maybe the companionship of someone you have known intimately for years and who wishes you dead only from time to time, but you know would never have the energy to kill you, is better than nothing, which is the only viable alternative.

The main priority for the late-middle-aged man is not to be a perv, or a predator. Which I really am not, so it’s no effort at all, although it’s probably just as important not to be seen as a perv or a predator.

I have known a few men who were genuine predators, and some who were actually proud of it. Such men often think they need women, and they certainly want women, but do they actually like women?

Each one was profoundly misogynist in his core, and all have generated chaos and destruction in the lives of the women they pursued and caught.

So if that’s the choice — be an alpha-male predator or become invisible — I shall happily take invisibility. Of course you could always chase one of those invisible middle-aged women. There are enough of them around. But would they notice? Would anyone?

In middle age, which seems to go on for ever, we get the first presentiments that the body does not come with an instruction manual. (Or, in the modern way, the manual is somewhere online, and you might get round to downloading it but you will never get round to reading it.)

Bodies start doing strange things we weren’t expecting. Noses and ears start sprouting hair where there was none before. Where once we could get away with only shaving every few days, some of us now have to shave almost hourly.

You have lost the gloss of youth, to be replaced by the dull emulsion of middle age. Was that it? you ask your body. Yes, says your body, and you’ve blown it.

So once you reach 60, you really have been through it. Your body is no longer the high-performance twin-camshaft speedster of your youth. It’s now a sputtering Ford Escort with chronic rust.

It’s different for everyone, of course.

Some of us have serious health problems, and one or two of us won’t recover from them. But most of us are knocking along all right, negotiating the gradual transfer from the middle lane of life to the slow lane, behind all the lorries and the cars towing caravans.

There’s only one consolation in all this: when you look in the mirror first thing in the morning and see a half-mad 75-year-old looking out at you, at least you know you probably have 15 years before you look like that all day.

Just as women above a certain age cannot hide their scraggy necks or liver spots on their hands, because life is cruel like that, so men can do nothing about their ears. They just keep growing. If you had small ears to start, then by 60 you will have normal-size ears.

If you had medium to large ears, the sky’s the limit — literally, if you’re in a high wind and you suddenly become airborne.

As we approach 60, all the blood that previously ran to our sexual organs now goes to our ears. This is why they go an unpleasant shade of purple whenever you see an attractive woman.

It is of course a vicious irony that as your ears grow ever larger, their ability to perform their primary function declines ever more swiftly. My own problem is tinnitus.

And why is there suddenly a small copse of hairs in each lughole? In this house they are referred to as ‘Daddy’s ear shrubbery’.

Occasionally you see a very old man with the usual huge ears and, inside them, a thicket so dense you would need a team of tiny gardeners wielding minuscule scythes to keep it under control. I used to see such men and think, ‘Poor guy’. Now I see them and think, ‘My future’.

By the age of 60 you’re lucky to have any hair left at all, and what there is has probably gone grey, or even white. For some reason it is perfectly acceptable for women to dye their hair all sorts of unusual colours, but when a man dyes his hair any colour at all, it looks ridiculous.

Paul McCartney has had more hits than anyone and has more money than the King, but the distressing shade of bright purple he used for so many years on his hair made him a figure of fun, the Ted Rogers de nos jours.

There’s something about hair dye that accentuates the ageing, saggy face beneath, but only on men. That this is unfair is apparent, but at 60 you should have stopped saying life is unfair at least half a century before.

The truth is that women are better at looking after themselves, because they have had a lifetime of being judged almost solely on appearances. So when they reach the nursery slopes of old age, they know what they are doing in a way that most straight men simply don’t. (The gay men of my acquaintance tend to be better preserved.)

A year or two ago I went to a college reunion of my contemporaries: my year, the year above and the year below. The women had all taken good care of themselves, and one or two were actually more attractive than they had been at 20. (Genuinely so: it was a pleasant surprise.)

Whereas the men, with a handful of exceptions, looked terrible. Huge bellies, disastrous combovers, great white beards, skin like overcooked gammon and, in one or two cases, an air of palpable defeat.

One, I had last seen when we graduated, when he was a rather chipper fellow with a decent line in dirty jokes and a Zapata-like black moustache. Now he was unimaginably small and frail with a huge white beard which looked as though it was growing him, rather than the other way round.

We had a brief chat, at the end of which he passed out, collapsed to the floor and had to be carried from the hall. I think he may have been quite seriously ill, although we didn’t talk about it, because men never discuss such things, especially after not seeing each other for 40 years.

But what did stick in the mind is that he was at most 18 months older than me.

This will sound like boasting — and even if it is, I don’t much care — but I am one of the better-preserved specimens of my generation, with (very nearly) a full head of hair of which only the temples have gone grey.

But I have always looked years younger than my age, and when I was 25, looking 15 was by no means an advantage. (The last time I was asked for ID when trying to buy alcohol, I was 37.)

Although I aged rather disconcertingly during the Covid menace, and now really struggle to get out of the bath without hydraulic equipment, I feel this is payback time.

We should never underestimate the sheer and lifelong trauma of losing your hair, because otherwise why would so many men invest in wigs and hair transplants? Wigs are a testament to man’s vanity — which is fine, as we are allowed to be vain — but also to man’s ineluctable foolishness.

Every man wearing a wig walks down the street thinking, with great pleasure, ‘I have a full head of hair.’ Everyone who passes him thinks, ‘That man is wearing a catastrophic wig.’

Only a very few rugs manage to pull off the impossible, which is to be so like real hair it never even occurs to you to try to pull it off. (I feel certain the desire to pull off another man’s wig is one of those human universals, like the need to jump into a pile of autumn leaves on the pavement, or when you are waving around a pretend lightsabre, the need to go ‘Zhummm! Zhummm!’ under your breath.)

I have more sympathy with people who get hair transplants, because although, like donning a rug, it’s almost always a mistake, it’s not one you can easily correct. Once installed, it’s there for good. And while wigs are inexpensive, hair transplants cost upwards of £10,000, which is probably about a pound a hair.

It’s also supposed to be quite painful, when you are having it done. I can’t imagine the level of psychological pain (horror at being bald) you must have to endure to go through the physical pain and the financial pain of having one put in, only to feel the pain of disappointment when it sits on your head like a stuffed ferret.

If men actually talked about such stuff, their friends would always advise them against. But obviously men do not.

When a friend of mine turned up to a get-together with a new hair transplant (to be fair, a very expensive and not bad-looking one), we all noticed, and no one said a word. There was an omertà of embarrassment. No one brought it up for a month or two.

But I think the shock was not that he had done it at all, but that we had all thought of our friend as a supremely confident and assured character, and his hair transplant demonstrated that he was far more vulnerable than he had appeared.

In that respect a hair transplant can say more about its owner than mere words ever can. Most of us had only known him 35 years or so.

Still A Bit Of Snap In The Celery by Marcus Berkmann (Abacus £16.99) to be published November 16. © Marcus Berkmann. To order a copy for £15.29 (offer valid to 27/11/23; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to www.mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.