Autoplay audio

In the days after the murder, the good people of Massachusetts thought they saw the shooter everywhere.

The Boston police broadcast his description far and wide: Black, male, 5’10”, 150 to 160 pounds, thin build, shaggy facial hair. And the community responded, calling in tip after tip to the dedicated hot line.

There he was, at the mall in blue Nikes; there he was, selling newspapers in Cambridge; there he was, walking through the leafy suburb of Canton with a limp. He looked “hinky,” he smelled like urine, he was almost 7 feet tall, he wore a black tweed coat. It was as if people could conjure him up by looking into a mirror and calling his name three times.

The police chased every single one of these leads. Hundreds of them. They came up empty-handed, again and again.

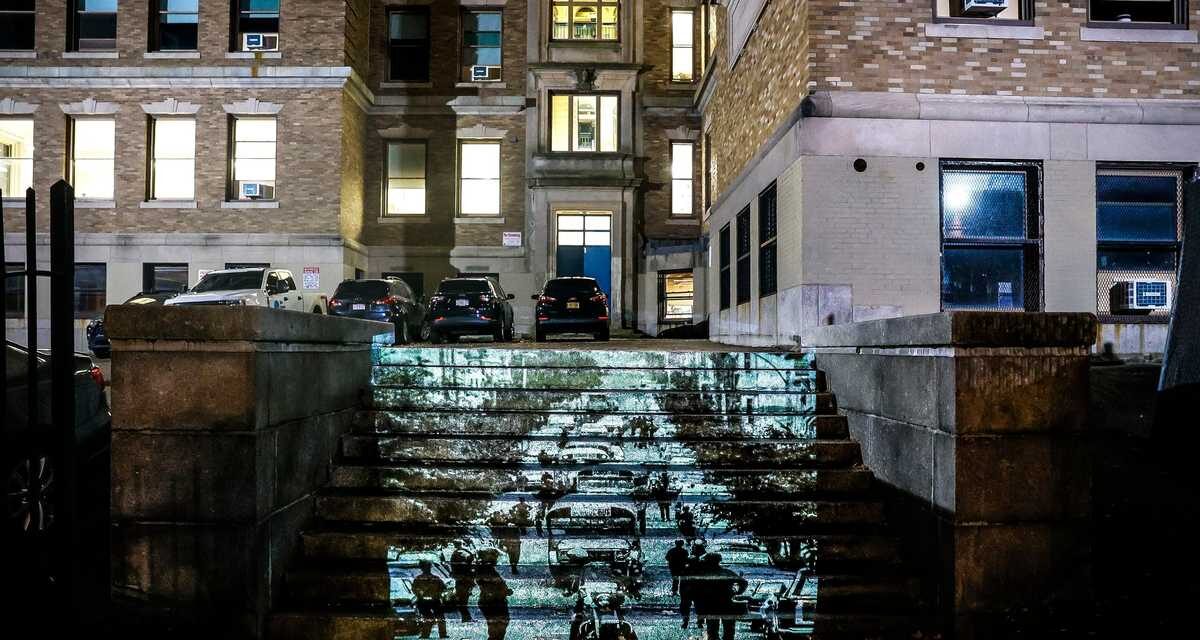

In the days after the shooting, Boston police officers fanned out across Mission Hill, stopping and searching Black men and boys in the neighborhood while looking for a suspect. (Tom Landers, George Rizer/Globe Staff)

Until Oct. 28, 1989 — five days into the biggest manhunt the city of Boston had ever seen, five days of searching for the shooter who murdered Carol Stuart and her baby and grievously wounded her husband, Chuck. Five days of citywide panic. And now, finally, a tip:

Word on the street was, the shooter was a guy named Albie.

This story had been circulating among Mission Hill’s drug users, and finally, somebody had flagged down an officer to pass it along.

Albie was known as a robber around Mission Hill. He had a silver gun and a drug problem, and ever since the shooting, he’d been acting real nervous, talking about making a plan to get out of the city because things were “too hot.” He was holed up with his girlfriend in a vacant apartment on Cornelia Court, not far from where the Stuarts were found, getting mad anytime anybody brought up the manhunt.

And, perhaps most importantly — Albie was Black, male, 5’10”, 160 pounds, thin build, with shaggy facial hair.

Officer Billy Dunn stood in a hallway on the second floor of 8 Cornelia Court, outside an apartment door that had just been slammed shut in his face. He considered his options. Sweet talk the door back open, or kick it down? One way or the other, he was getting inside.

This was the kind of moment Billy lived for. He was a 6-foot tall, 300-pound Irish Catholic bruiser from Dorchester nicknamed “the Legend.” Billy believed three things: That people were either born good, or born bad; that he was born good; and that his purpose on this earth was to protect the good from the bad.

And of course, it had been Billy who got the tip about Albie.

Out of all the 2,000 cops in the city of Boston, nobody knew Mission Hill better than Billy Dunn. He wasn’t a detective, he was a beat cop, and he spent every night patrolling up and down this quarter-mile stretch of the city. Other officers might shrink from an assignment like this one. Billy loved it.

He and his partner would ping-pong from one catastrophic call to the next, stanching bloody bullet wounds, pulling people out of fires, and dodging the rocks the kids threw at the cops just on principle. He’d lost count of the number of people he’d put away, the number he’d saved, and the awards he’d gotten. He prided himself that he always said a prayer over the bodies of the dead.

00:00

00:00

Boston police officer Billy Dunn in the late 1980s.

Billy was either hated or beloved, depending on whom you asked. He had been all over the news a few years earlier when he faced an accusation that he and other officers had raped a Black teenage girl. But they were cleared following a federal grand jury probe.

But back in the ‘80s — just about everybody in Mission Hill knew him. After Carol Stuart was murdered, the brass had detailed Billy to homicide, because if anybody was going to pry loose the neighborhood’s secrets, by charm or by force, it was the Legend.

And now, standing in this dimly lit hallway, staring at the closed door, Billy chose charm. He leaned forward and spoke through the door. He recalled that in the second or two it had been open, he’d seen a woman’s face, and then someone yanking her backward. Billy figured she might be persuadable.

He was right. After a minute or two, the door eased open, and Billy stepped inside.

And there, so high they were floating, were Albie and his girlfriend — otherwise known as Alan Swanson and Pamela Scott.

But that wasn’t what made Billy’s heart race. No. What made Billy’s heart race was what he saw in the bathroom.

There, in the sink, black fabric floated in pinkish water. He stepped closer, and he knew.

It was the shooter’s uniform: a striped black track suit.

On the back of the toilet seat, Billy saw a stack of newspaper clippings — every last one of them about the Stuart murder.

This was it. This was the guy.

Billy called out the bathroom door to his partner: Call homicide!

Two days later, The Boston Globe ran a story about Alan “Albie” Swanson’s arrest. It appeared alongside a front-page article about the rising tide of support for bringing back the death penalty in the wake of the Stuart slaying.

“My hope is that with the climate of Roxbury and Dorchester seeming like downtown Beirut, we can move this along,” a state senator said in the article as he tried to rally votes for his bill to reinstate capital punishment.

Capital punishment had been ruled unconstitutional in Massachusetts in 1984, but if there was ever a case calling for the return of the electric chair, Boston seemed dead set: This was it.

Police photo of Alan Swanson, the first man to be wrongly linked to the Stuart murder. Prosecutors arraigned Swanson on a charge of breaking and entering while police sought to make their murder case. (Boston Police)

Prosecutors arraigned Swanson on a charge of breaking and entering in an effort to buy police time to make their murder case. A judge ordered Swanson held on bail and sent him to the city jail, where guards and prisoners alike called him a baby killer and spat in his food.

For a few days, as the headlines turned to the arrest of a suspect, the fear that had gripped the city seemed to ebb.

But soon, reports began to leak out that police were wobbly on whether the 29-year-old petty criminal they had behind bars really made sense as their prime suspect. Even in his mug shot, Swanson looked small-time, with his eyes more than half closed and his head drooping sideways.

Detectives had hoped to find blood in the pinkish water where Billy Dunn found the track suit. But it turned out it was just dirty. And they never found his rumored silver gun.

“The fact is, that at any given point in time, we’re looking at three or four people,” an unnamed officer told a reporter. “We look at three or four every day.”

Meanwhile, Mayor Ray Flynn set out to do damage control, making the rounds at Black churches and neighborhood events to try to quell the growing outrage that — after a six-week stretch that saw 100 shootings with mostly Black victims — it was only the murder of a white woman that inspired the city to act.

“I’m out telling people, it’s a time to come together, not divide,” Flynn said after leaving a service at Morning Star Baptist Church, where he’d pleaded with 250 Black congregants to tamp down their feelings of hurt and anger for the greater good of the city.

This refrain — come together, not divide — was classic Ray Flynn. He had been elected twice as mayor on the promise that he could bring racial healing to a deeply wounded city.

In these early days of the Stuart investigation, Flynn still had faith that he could navigate the crisis by appealing to the better angels of his constituents. But many Black people heard his call for unity for what, perhaps, it really was: a call for Black people to forgive, again, the things that white people did to them.

As Flynn raced around the city stepping into pulpits and talking about the path to the future, the past nipped at his heels.

Boston, like anywhere else, is selective about which parts of its history it celebrates. People prefer to remember the good. It was here that the American Revolution began with a volley of gunfire; where abolitionists conspired and Harriet Tubman raised money for the Underground Railroad. Enslaved people found freedom in Boston, whose early prosperity had been rooted in the Colonial-era slave trade; Frederick Douglass gave landmark speeches; and Martin Luther King Jr. led marches on the Common.

00:00

00:00

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaking out against segregation at a joint session of the Massachusetts Legislature on April 22, 1965. King said he came to the Bay State not to condemn but to encourage, and warned “that from these halls liberty must be preserved.” (Paul Connell/Globe Staff)

But there is a darker history here, too. It centers on the busing of Boston’s schoolchildren in the 1970s.

This was the history that forged Flynn as a politician — and threatened now to undo him, and the city he led.

In 1974, when Flynn was still just an ambitious state representative, a federal judge named W. Arthur Garrity Jr. determined that Boston was running two separate school systems: one for white children, and one for Black children.

This was a clear violation of the Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which declared “separate but equal” unconstitutional. Judge Garrity ordered Boston to fix it, by busing Black kids to white schools, and white kids to Black schools.

A photograph of a bus with broken windows, carrying students as it returned to Columbia Point on Sept. 12, 1974, is projected on the former South Boston High School. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

Black parents worried. White parents revolted.

The fall of ‘74 kicked off with fury, as mobs of white residents waited for the buses carrying Black kids to hurl rocks, brawl with the cops, and shout racial slurs.

The frenzy was the fiercest in South Boston, or Southie, as everybody called it. Southie was working class and poor, with all-white public housing. Black people did not go there.

00:00

00:00

And who was the state rep that represented Southie? None other than Ray Flynn.

As the residents of Southie rose up against busing, Ray rose with them. These were his people.

A newscaster once said that if Norman Rockwell wanted to paint a portrait of the quintessential South Boston child, he should have Ray sit for him, and he was right. Flynn was white, Irish Catholic, and blue collar; his father was a union longshoreman and his mother a cleaning lady. He grew up on East Sixth Street, where now the buses carrying the Black kids lined up.

So Flynn greeted those buses from the steps of Southie High — where he had graduated — and watched white parents throw bricks. He put in 16-hour days going to meetings and motorcades, raising money for alternative schools, and briefing himself on constitutional law in hopes of fighting the desegregation order in the courts. He vowed to go “as far as necessary and take any and all steps to oppose busing.”

Flynn viewed the fight as an issue of class, not race. Poor families, he said, were sacrificing their kids for a social experiment, and being labeled racist for objecting. He opposed the violence, but he understood why people were enraged.

Mass. State Police and Metropolitan District Commission Police officers guarded a school bus outside of South Boston High School on Oct. 10, 1974. The initiative to desegregate Boston Public Schools was met with strong resistance from many residents of Boston’s neighborhoods. (Ted Dully/Globe Staff)

In early December, a fed-up Black student stabbed a white student in Southie High, and thousands of white people left work to descend on the school. The police had to bring in decoy buses, and the mob shattered the windows as the Black kids ran out the back door.

Meanwhile, Flynn mulled a run for mayor on an antibusing platform, and bumper stickers reading “We want Flynn in ‘75” multiplied on cars parked at Southie curbs.

But the crusade against busing was a losing political proposition. The clashes spread across the city, to Charlestown and Hyde Park and the plaza of City Hall. The Ku Klux Klan jumped into the fray. And this went on for years. A lot of parents, white and Black, just stopped sending their kids to school.

The footage of all the ugliness broadcast nightly on the TV news turned Boston — and Ray Flynn’s Southie in particular — into a national symbol of America’s deep racial bigotry.

There was one photograph that came to define the entire busing era — and, to many people, Boston itself.

It was taken at City Hall Plaza by a news photographer in 1976 during a rally against busing, when a group of white teenagers carrying a flag attacked a Black lawyer named Ted Landsmark.

At a Boston rally against forced school busing, white teenager Joseph Rakes brandished an American flag at Ted Landsmark on April 5, 1976. The photo, which would come to be known as “The Soiling of Old Glory,” rocketed around the world. (Stanley Forman)

On one side of the frame, Landsmark is frozen in motion, mid-attack. He’s stumbling backward, his nose broken and his perfectly pressed three-piece-suit crumpling. On the other side, a white teenager lunges, wielding the flagpole like a spear. The pointed tip appears aimed right at Ted’s gut. The American flag flutters between them.

The furor over busing died down as the 1970s drew to a close. Flynn never did launch his antibusing run for mayor.

Instead, in the early 1980s, he reinvented himself as a scrappy liberal champion of the underdog, white or Black.

Now, when he talked about his childhood, he told stories of walking across a bridge that led out of Southie to play basketball with the Black kids. When he reflected on busing, he talked about class, not race, and how much poor white people and poor Black people had in common.

And it was this Flynn — the bridge-crossing white kid who believed in coming together — that the people of Boston finally elected mayor in 1983. Flynn bested Mel King, the first Black candidate to ever make it to the general election.

“We have a united city where the voice of every neighborhood in this city has been heard,” Flynn declared on the night he won. “We have proven that the hopes that unite us are stronger than the fears that separate us.”

To today’s ear, that may sound like generic kumbaya political-speak, but to Bostonians in 1983, Flynn’s meaning was clear: The wounds of busing were closing.

00:00

00:00

Boston mayoral candidate Ray Flynn (left) reviewed notes before a televised debate with opponent Mel King (right) on Oct. 26, 1983. Mayor Ray Flynn walked with Dan Richardson of the Trotter Neighborhood Association during a press conference about a local development on Aug. 31, 1985. (John Tlumacki, John Blanding/Globe Staff)

They weren’t, of course, but Flynn really was trying. He started showing up personally at the scene of every act of racial violence. He fought racist redlining practices by banks, created jobs for people of color, and in the late 1980s, desegregated the city’s public housing complexes. He appointed a new police commissioner — Mickey Roache — who had made a name for himself running the Police Department’s civil rights office.

Flynn staffed his administration with a cadre of progressive activists — including Landsmark, the Black lawyer attacked with the flag in the famous photograph.

And so, as the hot summer of 1989 wound down and the leaves started turning orange and yellow and Carol Stuart walked out the doors of Brigham and Women’s Hospital into the last night of her life, Flynn was feeling pretty good about the direction things were heading.

And then, those two words, uttered from the back of an ambulance by a gasping Charles Stuart:

“Black… Man.”

A totally generic description. And that was its power. Chuck had tapped into an old American myth: the story of the Black boogeyman. White people have been seeing him since the founding of the country.

He was there in the Mississippi Delta, where a gang of white men lynched a 14-year-old Black boy named Emmett Till for offending a white woman in 1955. He showed up in Tulsa, Okla., where in 1921 a furious white mob burned down the Black side of town after a Black man interacted with a white woman in an elevator. America’s deep dark soil holds the ghosts of thousands of such Black lives.

On the night of the shooting, Flynn the racial healer walked up to the microphones inside the police station and promised that every available detective would work the case. The police would find this cold-blooded killer.

Flynn gave the people the thing he knew they wanted:

A crackdown.

But Boston Police Detectives Robert Ahearn and Robert Tinlin weren’t so sure about the path the city seemed to have settled on.

A week into their investigation, their doubts about Chuck were growing.

When they had interviewed him, he reminded them both of another case they worked: a white guy by the name of John Jenks, who shot a Black man then shot himself to make it look like he was the victim. They’d interviewed Jenks in his hospital bed, and just like Chuck, he had seemed too calm.

There was one big difference, though — Jenks had suffered a superficial wound. Chuck had very nearly died. His surgeon — Boston City Hospital’s chief of trauma, who had seen thousands of bullet wounds as a surgeon in Vietnam — said it was impossible that Chuck had shot himself due to the location of the entry wound, in Chuck’s lower back, and the upward angle of the bullet’s path.

If Chuck was lying, it was a brilliant cover.

A photograph from 1984 is projected in Brigham Circle on Wait Street in Mission Hill, with Brigham and Women’s Hospital seen in the distance. (Erin Clark/Globe Staff)

At about 8:45 p.m. on Monday, Oct. 30 — the same day and time as the shooting, but one week later — the Bobbies borrowed a car with a tape deck and popped a recording of Chuck’s 911 call in. Then, they drove from the Brigham, to the spot where Chuck said the Black man jumped into their car, and hit “play.”

They wanted to see if the route Chuck described — which deposited him a half mile from the hospital, pointing the wrong direction — made any sense.

They crossed Huntington, drove down Tremont, and hooked a left onto Gurney. They rolled up to a half-demolished bar where a yellow Schlitz sign still beckoned. It was in front of this bar, the Station Cafe, that they were pretty sure the shooting happened. They rumbled past, and took a left, then a left, then a right out onto Tremont, headed back toward the Brigham.

So far, the route held up. But one thing struck them both: The streets were busy at that hour. There were people everywhere. Why hadn’t Chuck been able to find help?

Then came the final turn. They could practically see the hospital lights ahead. But just before he passed out, Chuck had gone right — away from the hospital, back into the public housing complex. It didn’t make sense.

Later, in the confines of their second-floor office in homicide, Ahearn and Tinlin mulled over their concerns.

They were starting to feel like they were losing control of their case. There was Billy Dunn’s arrest of Alan Swanson, which no one had even bothered to tell them about. That had pissed them off. Swanson was still in jail, and every second that ticked by gave the real killer a better defense.

In early November, Ahearn told the head of the homicide unit that he and Tinlin thought Chuck was their shooter.

All right, see what you can do on it, the head of homicide replied. We’re also going in another direction.

Not long afterwards, the Bobbies took a few days off. When they came back to work, they discovered that the Stuart murder files had been taken out of their office. It wasn’t their case anymore.

Now, the Stuart case belonged to a new set of detectives, and they had themselves a new suspect.

He was a notorious figure in Mission Hill, a dangerous tough guy who had started two separate shootouts with police, who didn’t care if he lived or died so long as he went down firing. He was erratic and drugged out and capable of anything.

His nickname was “Wild Bill.”

Advertisement