The study population consisted of 13,779 ICs who provided care over the previous 30 days and completed the BRFSS survey in 2019 or 2020. Out of those 13,779 ICs, 3,638 were excluded from the analysis because they provided care both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic or because it was unclear whether their care provision status overlapped between the period before and during COVID-19 pandemic. The final sample consisted of a total of 9,240 ICs, who provided complete data on their sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race-ethnicity, educational attainment, and relationship to the care recipient). A weighted 90.03% (N = 8,379) of the ICs in the sample provided care before the COVID-19 NED, and 9.97% (N = 861) provided care after the COVID-19 NED went into effect.

Table 1 presents the weighted demographic characteristics of the sample, both total and by the COVID-19 NED status. The 861 ICs who provided care during the COVID-19 pandemic were successfully matched with 1,722 controls (selected among those who provided care before the COVID-19 NED). An adequate covariate balance (i.e., all SMD < 0.20) was achieved using 2:1 propensity score matching (Supplementary Figs. 1–2), with a caliper of 0.11.

Table 2 presents a summary of weighted descriptive statistics across baseline characteristics for each outcome of interest in the matched data. Descriptively, the average number of days of poor physical health was observed to be higher among those who provided care before the COVID-19 NED (4.62 days) compared to those who provided care after the COVID-19 NED (3.41 days). However, the mean number of days of poor mental health observed was only slightly higher among those who provided care after the COVID-19 NED (5.68 days) compared to those who provided care before the COVID-19 NED (5.35 days).

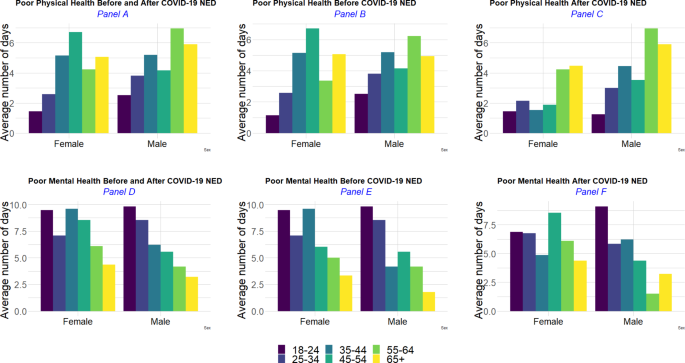

The reported mean number of days of poor physical and mental health differed across age groups: younger age ICs (i.e., < 25 years) reported a higher average number of days of poor mental health (8.66 days in this age group) compared to older ICs (3.19 days among those 65+). However, the average number of days of poor physical health was observed to be lower among those < 25 years (1.51 days) compared to those 65+ (5.04 days).

Male ICs were observed to have a slightly higher average number of days of poor physical health compared to female ICs (e.g., 4.52 versus 3.82 days); whereas female ICs reported a higher mean number of days of poor mental health compared to male ICs (e.g., 5.90 versus 4.89 days). Across all age groups, male ICs reported higher averages of poor physical health days compared to female ICs within the same age groups, except for female ICs aged 45–54 years, who reported a higher observed average number of days of poor physical health compared to male ICs of the same age group. However, female ICs consistently reported a higher observed average number of days of poor mental health compared to male ICs of similar age groups, and this trend held across all age groups, except for 25–34 years old group (Fig. 1). Compared to the period before the COVID-19 NED, the observed average number of days of poor physical health after the COVID-19 NED decreased in both sexes across most age groups; except for the youngest female ICs (18–24 years old); female ICs aged 55–64; and older male ICs (55 + years old). The observed average number of days of poor mental health decreased from its levels prior to the COVID-19 NED among younger female ICs (< 45 years old); whereas older female ICs (45 + years old) reported on average higher numbers of days of poor mental health, compared to before the COVID-19 NED. Among young male ICs (< 35 years old), the period following the COVID-19 NED saw a lower observed average number of days of poor mental health compared to its levels prior to the COVID-19 NED. However, among male ICs aged 35–44 and 65 years and older, the period following the COVID-19 NED recorded a higher observed average number of days of poor mental health compared to its levels prior to the COVID-19 NED (Fig. 1).

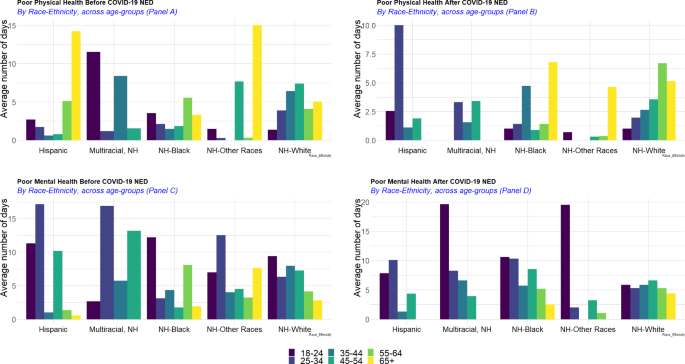

On average, non-Hispanic White ICs reported the highest number of days of poor physical health (4.58 days) and ICs who identified as non-Hispanic other races had the lowest observed average number of days of poor physical health (1.99 days) in the combined period. By contrast, non-Hispanic Black and White ICs had the lowest observed average number of days of poor mental health (5.29 and 5.31, respectively) compared to individuals with another racial/ethnic group identity. People who identified as non-Hispanic multiracial reported the highest number of days of poor mental health (8.16 days on average) (Fig. 2). Across race-ethnicity stratification, middle-age [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] ICs self-identified as non-Hispanic other races and older (55 + years of age), non-Hispanic multiracial ICs had the lowest observed average numbers of days of poor physical and physical health. Older non-Hispanic other races ICs (65+) had the highest observed average number of days of poor physical health (on average 9.7 days of poor physical health), compared to other race-ethnicity groups. The highest average number of days of poor mental health was reported among younger ICs (18–24 years old group) self-identifying as non-Hispanic other races, as well as Hispanic ICs aged 25–34; whereas the lowest average number of days of poor mental health was recorded among older Hispanic (65 + years) and non-Hispanic multiracial ICs (55 + years of age).

Prior to the COVID-19 NED, older ICs (65 + years of age) of Hispanic origins and non-Hispanic other races had the highest observed average number of days of poor physical health (on average more than 13 days of poor physical health), however after the COVID-19 NED older (55 + years) Hispanic ICs and middle age [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] ICs of non-Hispanic other race origins had the lowest average number of days of poor physical health (Fig. 3, panels A and B), though the numbers of respondents are smaller for some of these subpopulations. Hispanic ICs aged 25–34 experienced the biggest increase in the average number of days of poor physical health (from 1.71 days to 10.00 days); also, non-Hispanic Black ICs aged 35–44 and 65 + years and older non-Hispanic White (55 + years of age) reported higher numbers of days of poor physical health after the COVID-19 NED compared to the period before the COVID-19 NED.

In terms of mental health (Fig. 3, panels C and D), Hispanic and multiracial non-Hispanic ICs aged 25–34 reported the highest average number of days of poor mental health before the COVID-19 NED. After the COVID-19 NED, young (< 25 years) non-Hispanic multiracial and non-Hispanic ICs of other races experienced the highest average number of days of poor mental health. Across the other racial-ethnic groups, the average number of days of poor mental health increased among non-Hispanic Black (e.g., 25–54; and 65 + years of age) and older non-Hispanic White (55 + years of age).

Incidence rate ratios of reported days of poor physical health

Table 3 includes adjusted incidence rate ratios and corresponding p-values from the weighted negative binomial regressions using the 2:1 matched sample. The adjusted incidence rate of poor physical health days was 26% lower (p = 0.001) among ICs who provided care after versus before the COVID-19 NED. The incidence rate of reporting days of poor physical health was 69% lower (p < 0.001) among ICs aged 18–24 compared to those aged 65+. The incidence rate for reporting days of poor physical health was 44% lower (p = 0.001) among ICs aged 25–34 compared to those aged 65+. The incidence rates of reporting days of poor physical health were higher for ICs with lower educational attainment (e.g., 2.03; and 1.68 times higher, respectively, for those with no high school diploma, those with high school diploma only, and those who attended college or technical school without obtaining a degree, respectively) compared to those who graduated from college or technical school). The incidence rate of reporting days of poor physical health was 30% lower (p = 0.005) among non-Hispanic Black ICs compared to non-Hispanic White ICs. The incidence rate of reporting days of poor physical health was 46% (p = 0.042) among those identifying as non-Hispanic of other races compared to non-Hispanic White. The relationship with the care recipient was non-significant (p ≥ 0.844).

Incidence rate ratios of reported days of poor mental health

The adjusted incidence rate of reported days of poor mental health was not statistically different (p = 0.730) between informal caregiving before versus after the COVID-19 NED, nor across racial/ethnic identities (p > 0.591) when compared to non-Hispanic White individuals. The incidence rate of reported days of poor mental health stood higher at younger ages compared to older ages. For example, ICs aged 18–24 had 3.32 times higher incidence rates than those aged 65 years and older (p < 0.001). Similar results were found across age groups, with smaller differences as age gaps narrowed.

The incidence rate of reported days of poor mental health was 29% lower (p < 0.001) among male ICs compared to female ICs. Those with generally lower education had higher incidence rates of reporting days of poor mental health compared to graduates from college or technical school (p ≤ 0.012), although the comparison with those who did not graduate from high school was non-significant (p = 0.095). Furthermore, the incidence rate of poor mental health days was 37% higher for IC for a sibling, spouse, or brothers- and sisters-in-law (p = 0.004) compared to that of intergenerational relatives (including father, mother, child, grandparents, parents-in-law, and grandchild); whereas no significant difference was found for IC to other relatives or friends.

Supplementary Figs. 3–4 portray the residual plots for both models.

Sensitivity analysis

Results from the hot-deck imputed data were comparable to those in the complete case analysis. There were 448 missing observations imputed from the original sample of ICs, who provided care before or during the COVID-19 pandemic but had missing sociodemographic characteristics. Overall, a weighted 10.72% of the ICs provided care after the COVID-19 NED upon imputation, compared to 9.97% in the main analysis (Supplementary Table 1). Covariate balance was achieved using propensity score matching, with all standardized mean differences below 0.20 (Supplementary Fig. 5).

In the imputed, 2:1 matched sample, 1,003 ICs who provided care after the COVID-19 NED were successfully matched to 2,006 controls (ICs who provided care before the COVID-19 NED). Like in the primary analysis, the average number of days of poor physical health was observed to be higher (5.16 days) among ICs who provided care before the COVID-19 NED compared to those who provided care after the COVID-19 NED (3.72 days) (Supplementary Table 2). Days of poor mental health were higher (6.28 days) among those who provided care after the COVID-19 NED compared to those who provided care before the COVID-19 NED (5.40 days). At younger age ranges, ICs reported fewer days of poor physical health, but more days of poor mental health, whereas at older ages this was reversed. Likewise, ICs with low educational attainment reported on average a higher number of days of poor physical and mental health.

Results from the negative binomial regression models (Supplementary Table 3) showed similar results to that of the primary analysis – i.e., that although informal caregiving during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with decreased incidence rates of days of poor physical health (p < 0.001), there was no significant difference in the incidence of poor mental health days (p = 0.075) among ICs before versus after the COVID-19 NED. In comparison, at younger ages (all age groups less than 65 years old; all p < 0.001), the incidence rate of reported poor mental health days was higher than for those aged 65+. Lower educational attainment was similarly associated with a higher incidence rate of reported poor mental and physical health days (all p-values < 0.001 across all education levels compared to those with a college or technical school degree).