Larnell Robinson sat at a desk in his cluttered office last September, between a bookshelf full of Bibles and a table stacked with the overdose antidote Narcan. He slid out a list of residents of the West Baltimore high-rise where he was tenant council president — one of dozens of subsidized complexes that house the city’s poor seniors. One by one, he began scratching through names, conducting a grim accounting of the dead.

William, 63, killed by fentanyl and found in his ninth-floor unit in February 2023. Richard, 61, discovered in an apartment with multiple drugs in his system two and a half weeks later. David, 68, three days after that, also dead from fentanyl.

And then 59-year-old Glenn, who had lived on Mr. Robinson’s floor for years. Known for his willingness to run errands for others, he often biked to the store to get Mr. Robinson cigarettes. But after not seeing Glenn for a day, Mr. Robinson stuck a flier in his door. When it was still there the next morning, he summoned security.

This was one death, Mr. Robinson said later, that he couldn’t bear to witness. “I feel like I work at the morgue sometimes,” he said in an interview.

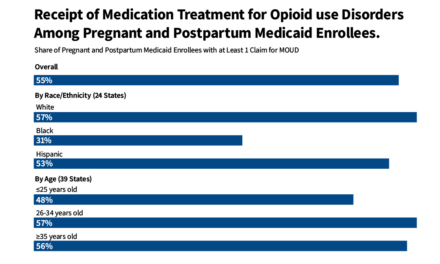

Over the past six years, as Baltimore has endured one of America’s deadliest drug epidemics, overdoses have fallen surprisingly hard on one group: Black men currently in their mid-50s to early 70s. While just 7 percent of the city’s population, they account for nearly 30 percent of drug fatalities — a death rate 20 times that of the rest of the country.

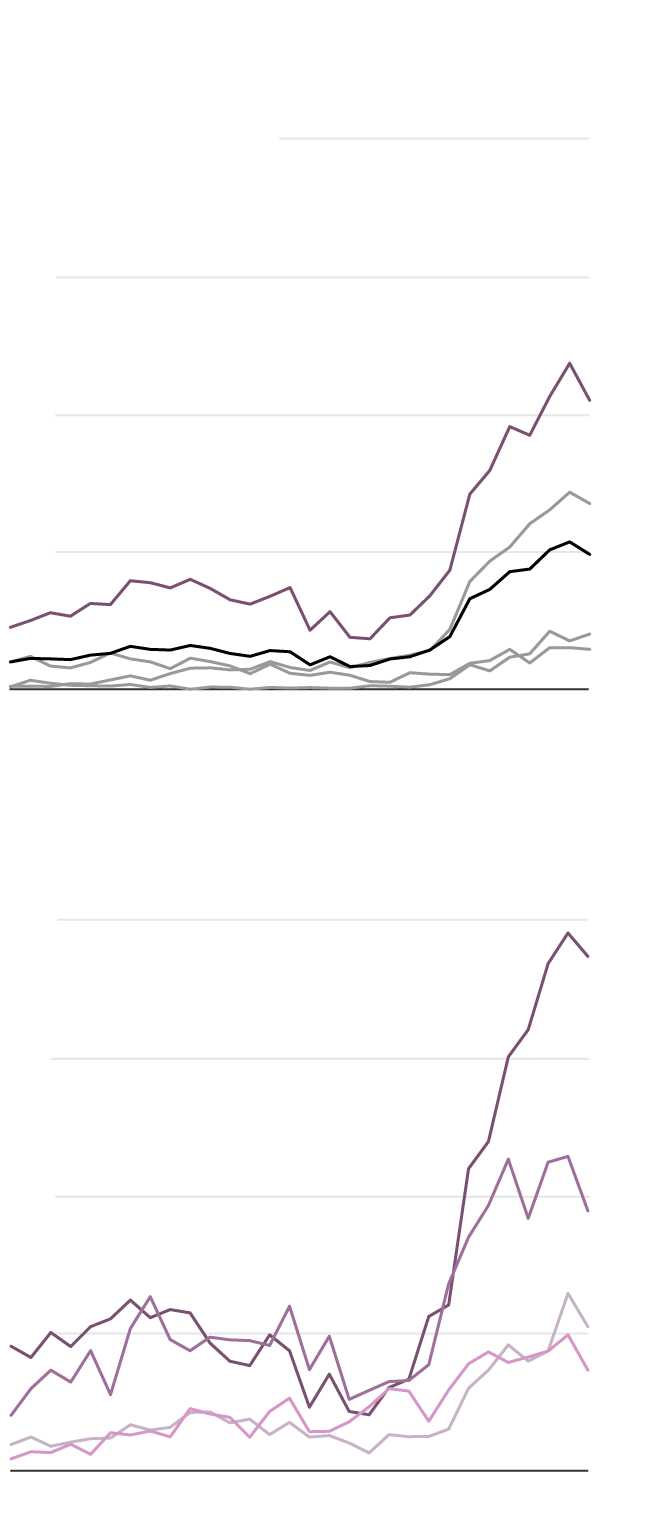

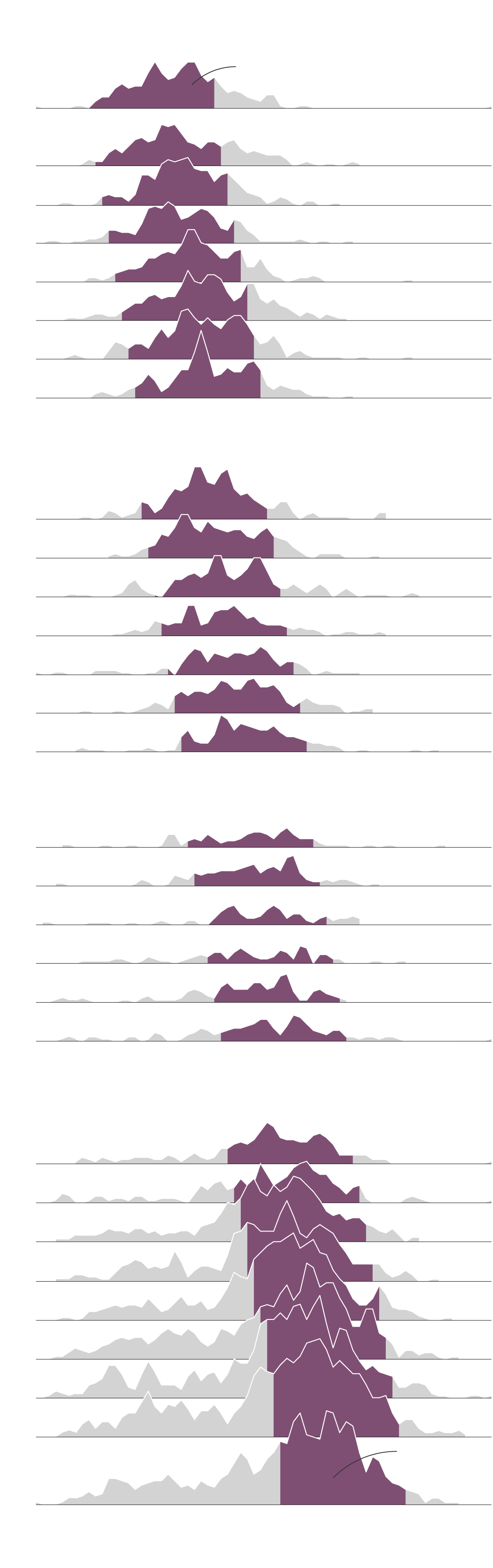

A generation devastated by drugs

People born between 1951 and

1970 have fatally overdosed at

the highest rates in Baltimore.

800 deaths per 100,000

600

BORN

BETWEEN:

1951-

1970

400

1971-

1990

200

All

1991-

2010

1931-

1950

1993

2022

Within that generation, Black men have

far exceeded other demographic groups.

800

Black

men

600

400

White

men

Black

women

200

White

women

1993

2022

800 deaths per 100,000

Black

men

People born between 1951 and

1970 have fatally overdosed at

the highest rates in Baltimore.

Within that generation,

Black men have far exceeded

other demographic groups.

600

BORN

BETWEEN:

1951-

1970

400

White

men

1971-

1990

Black

women

200

All

White

women

1991-

2010

1931-

1950

1993

2022

1993

2022

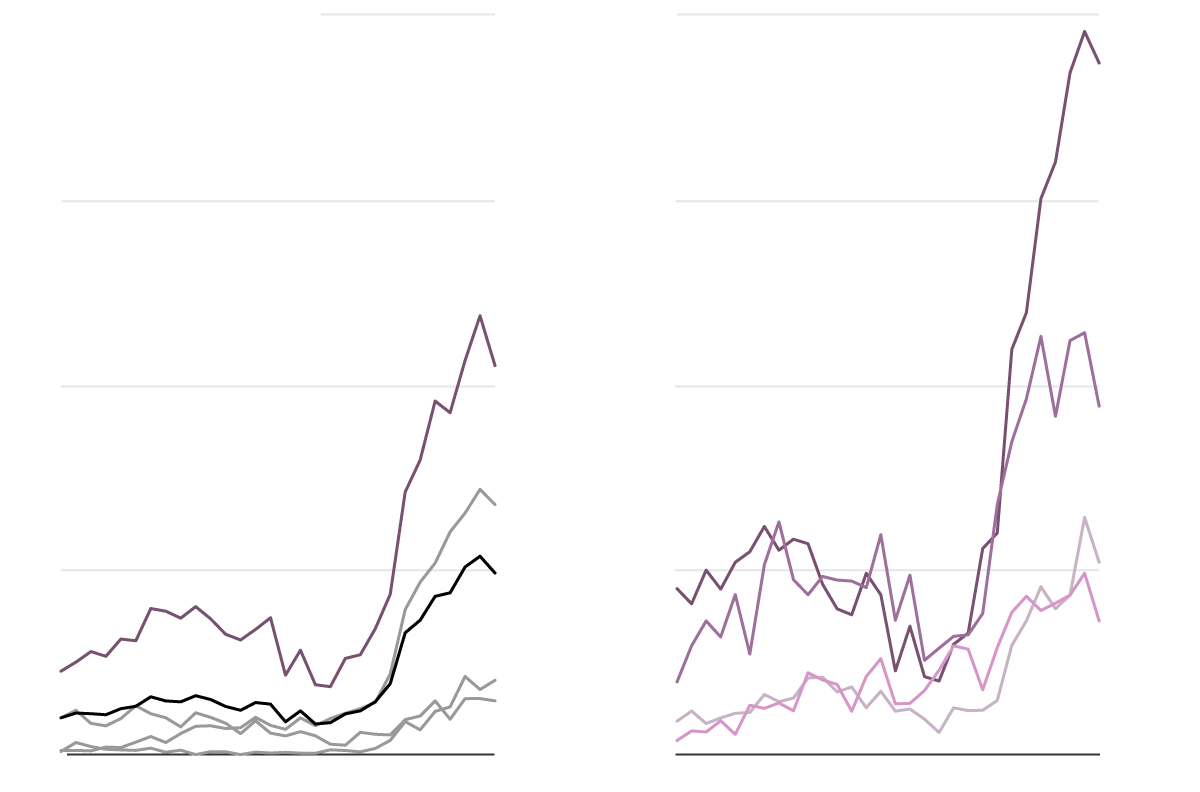

Drug deaths among Baltimore’s Black men

This chart shows decades of fatal overdoses

among Black men in Baltimore, with those

born between 1951 and 1970 highlighted

in dark purple.

118 out of

155 total deaths

1993

23

42

Ages

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

30

49

Ages

As they got older, the bulk of the city’s

overdose victims aged with them.

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

37

56

Ages

In the mid-2000s, fatal drug overdoses

dropped to an all-time low. But men of

this age still died the most.

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

43

62

Ages

In 2013, as these men entered middle age,

fentanyl began making Baltimore’s drug

supply more addictive and extremely deadly.

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

277 out of

465 total deaths

2022

52

71

Ages

By 2022, as these men were in their

early 50s to early 70s, they were dying

in tremendous numbers.

This chart shows decades of fatal overdoses among Black men in Baltimore,

with those born between 1951 and 1970 highlighted in dark

purple.

118 out of

155 total deaths

1993

42

23

Ages

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

30

49

Ages

As they got older, the bulk of the city’s overdose victims aged with them.

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

56

37

Ages

In the mid-2000s, fatal drug overdoses dropped to an

all-time low. But men of this age still died the most.

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

43

62

Ages

In 2013, as these men entered middle age, fentanyl began making

Baltimore’s drug supply more addictive and extremely deadly.

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

277 out of

465 total deaths

2022

52

71

Ages

By 2022, as these men were in their early 50s to early 70s,

they were dying in tremendous numbers.

Got a confidential news tip?

The New York Times would like to hear from readers who want to share messages and materials with our journalists.