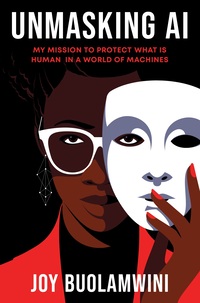

Computer scientist Joy Buolamwini was a graduate student at MIT when she made a startling discovery: The facial recognition software program she was working on couldn’t detect her dark skin; it only registered her presence when she put on a white mask.

It was Buolamwini’s first encounter with what she came to call the “coded gaze.”

“You’ve likely heard of the ‘male gaze’ or the ‘white gaze,'” she explains. “This is a cousin concept really, about who has the power to shape technology and whose preferences and priorities are baked in — as well as also, sometimes, whose prejudices are baked in.”

Buolamwini notes that in a recent test of Stable Diffusion’s text-to-image generative AI system, prompts for high paying jobs overwhelmingly yielded images of men with lighter skin. Meanwhile, prompts for criminal stereotypes, such as drug dealers, terrorists or inmates, typically resulted in images of men with darker skin.

In her new book, Unmasking AI: My Mission to Protect What Is Human in a World of Machines, Buolamwini looks at the social implications of the technology and warns that biases in facial analysis systems could harm millions of people — especially if they reinforce existing stereotypes.

“With the adoption of AI systems, at first I thought we were looking at a mirror, but now I believe we’re looking into a kaleidoscope of distortion,” Buolamwini says. “Because the technologies we believe to be bringing us into the future are actually taking us back from the progress already made.”

Buolamwini says she got into computer science because she wanted to “build cool future tech” — not to be an activist. But as the potential misuses of the technology became clearer, she realized she needed to speak out.

“I truly believe if you have a face, you have a place in the conversation about AI,” she says. “As you encounter AI systems, whether it’s in your workplace, maybe it’s in the hospital, maybe it’s at school, [ask] questions: ‘Why have we adopted this system? Does it actually do what we think it’s going to do?’ “

Interview highlights

On why facial recognition software makes mistakes

How is it that someone can be misidentified by a machine? So we have to look at the ways in which we teach machines to recognize the pattern of a face. And so the approach to this type of pattern recognition is often machine learning. And when we talk about machine learning, we’re talking about training AI systems that learn from a set of data. So you have a dataset that would contain many examples of a human face, and from that dataset, using various techniques, the model would be trained to detect the pattern of a face, and then you can go further and say, “OK, let’s train the model to find a specific face.”

What my research showed and what others have shown as well is many of these datasets were not representative of the world at all. I started calling them “pale male” datasets, because I would look into the data sets and I would go through and count: How many light-skinned people, How many dark-skinned people? How many women, how many men and so forth. And some of the really important data sets in our field. They could be 70% men, over 80% lighter skinned individuals. And these sorts of datasets could be considered gold standards. …

And so it’s not then so surprising that you would have higher misidentification rates for people who are less represented when these types of systems were being developed in the first place. And so when you look at people like Porcha Woodruff, who was falsely arrested due to facial recognition misidentification, when you look at Robert Williams, who was falsely arrested due to facial misidentification in front of his two young daughters, when you look at Nijeer Parks, when you look at Randall Reed, Randall was arrested for a crime that occurred in a state he had never even set foot in. And all of these people I’ve mentioned – they’re all dark-skinned individuals.

On why AI misgenders female faces

I looked at the research on gender classification, I saw with some prior studies, actually older women tended to be misgendered more often than younger women. And I also started looking at the composition of the various gender classification testing datasets, the benchmarks and so forth. And it’s a similar kind of story to the dark skin here. It’s not just the proportion of representation, but what type of woman is represented. So, for example, many of these face datasets are face datasets of celebrities. And if you look at women who tend to be celebrated, [they are] lighter skin women, but also [women who] fit very specific gender norms or gender presentation norms and stereotypes as well. And so if you have systems that are trained on some type of ideal form of woman that doesn’t actually fit many ways of being a woman, this learned gender presentation does not reflect the world.

On being a “poet of code,” and the success of her piece, “AI, Aint I a Woman?”

I spent so much time wanting to have my research be taken seriously. … I was concerned people might also think it’s a gimmick. … And so after I published the Gender Shades paper and it was really well received in the academic world and also industry, in some ways I felt that gave me a little bit of a shield to experiment with more of the poetic side. And so shortly after that research came out, I did a poem called “AI, Ain’t I a Woman?,” which is both a poem and an AI audit from testing different AI systems out. And so the AI audit results are what drive the lyrics of the poems. And as I was working on that, it allowed me to connect with the work in a different way.

This is where the humanizing piece comes in. So it’s one thing to say, “OK, this system is more accurate than that system,” or “this system performs better on darker skin or performs better on lighter skin.” And you can see the numbers. But I wanted to go from the performance metrics to the performance arts so you could feel what it’s like if somebody is misclassified — not just read the various metrics around it.

And so that’s what the whole experimentation around “AI, Ain’t I a Woman?” was. And that work traveled in places I didn’t expect. Probably the most unexpected place was with the EU Global Tech panel. It was shown to defense ministers of every EU country ahead of a conversation on lethal autonomous weapons to humanize the stakes and think about what we’re putting out.

On her urgent message for President Biden about AI

We have an opportunity to lead on preventing AI harms, and the subtitle of the book is protecting What Is Human in a World of Machines. And when I think of what is human, I think about our right to express ourselves, the essence of who we are and our expectations of dignity. I challenge President Biden for the U.S. to lead on what I call biometric rights. …

I’m talking about our essence, our actual likeness. … Someone can take the voice of your loved one, clone it and use it in a hoax. So you might hear someone screaming for your name, saying someone has taken something, and you have fraudsters who are using these voice clones to extort people. Celebrity won’t save you. You had Tom Hanks, his likeness was being used with synthetic media with a deepfake to promote a product he had never even heard of.

So we see these algorithms of exploitation that are taking our actual essence. And then we also see the need for civil rights and human rights continue. It was very encouraging to see in the executive order that the principles from the Blueprint for an AI Bill of Rights — such as protections from algorithmic discrimination, that the AI systems being used are effective, that there are human fallbacks — were actually included, because that’s going to be necessary to safeguard our civil rights and our human rights.

On how catastrophizing about AI killing us in the future neglects the harm it can do now

I’m concerned with the way in which AI systems can kill us slowly already. I’m also concerned with things like lethal autonomous weapons as well. So for me, you don’t need to have super intelligent AI systems or advanced robotics to have a real harm. A self-driving car that doesn’t see you on the road can be fatal and harmful. I think of this notion of structural violence where we think of acute violence: There’s the gun, the bullet, the bomb. We see that type of violence. But what’s the violence of not having access to adequate health care? What’s the violence of not having housing and an environment free of pollution?

And so when I think about the ways in which AI systems are used to determine who has access to health care and insurance, who gets a particular organ, in my mind … there are already many ways in which the integration of AI systems lead to real and immediate harms. We don’t have to have super-intelligent beings for that.

Sam Briger and Thea Chaloner produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Beth Novey adapted it for the web.

9(MDAyMTgwNzc5MDEyMjQ4ODE4MjMyYTExMA001))

Transcript :

TONYA MOSLEY, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I’m Tonya Mosley. You’ve probably heard the male gaze or the white gaze, but what about the coded gaze? Computer scientist Joy Buolamwini coined the term while in grad school at MIT. As a brown-skinned, Black woman, the facial recognition software program she was working on couldn’t detect her face until she put on a white mask. This experience set Buolamwini on a path to look at the social implications of artificial intelligence, including bias in facial analysis technology and the potential harm it could cause millions of people like her – everything from dating app glitches to being mistaken as someone else by police. She’s written a new book about her life and work in this space called “Unmasking AI: My Mission To Protect What Is Human In A World Of Machines.” Last month, after meeting with Buolamwini and other AI experts, President Biden recently issued an executive order aimed at making AI safer and more secure.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN: This landmark executive order is testament to what we stand for – safety, security, trust, openness, American leadership and the undeniable rights endowed by a creator that no creator – no creation can take away, proving once again that America’s strength is not just the power of its example, but the example of its power.

MOSLEY: Joy Buolamwini is the founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, an organization that raises awareness about the implications of AI. She is also a Rhodes Scholar and has a Ph.D. from MIT. Her thesis uncovered large racial and gender bias in AI services from companies like Microsoft, IBM and Amazon. Buolamwini’s research was also featured in the Netflix documentary “Coded Bias.” And Dr. Joy Buolamwini, welcome to FRESH AIR.

JOY BUOLAMWINI: Thank you so much for having me.

MOSLEY: The coded gaze is this term that you coined a few years ago after an experience you had with a program that you were building called Aspire Mirror. Can you explain what the tech was supposed to do and why it couldn’t detect your face?

BUOLAMWINI: Sure. So at the time, I was a graduate student at the MIT Media Lab, and I took a class called Science Fabrication. The idea was to make something fanciful, so I made a kind of art installation that used face-tracking technology to detect the location of a person’s face in a mirror and then add a digital mask. And so this is what I was working on when things went a little sideways. So in that experience of working on the class project, which was an art installation, I found that the software I was using didn’t detect my face that consistently until I put on a white mask. I was working on the system around Halloween, so I happened to just have a white mask in my office.

So when I was debugging and trying to figure it out, that’s how I came to see that my dark skin wasn’t detected but the white mask was, and that led to all kinds of questions. Is it just my face? Is that the lighting conditions? Is it the angle, or is there something more at play? And so for me, this was really my first encounter with what I now term the coded gaze. And so you’ve likely heard of the male gaze or the white gaze. This is a cousin concept really about who has the power to shape technology and whose preferences and priorities are baked in, as well as also sometimes whose prejudices are baked in.

MOSLEY: Well, when you first started to speak about this, people said stuff to you like, well, I mean, it could be the camera ’cause there wasn’t a lot of light. There is no bias in math algorithms. You break apart this idea through your research on cameras. Can you briefly describe what you found?

BUOLAMWINI: Yes. I, too, wanted to believe that tech was completely neutral. That’s why I got to it, right? I thought…

MOSLEY: Yeah.

BUOLAMWINI: …OK, I can escape the isms and messiness of people, but when it came to the type of tech I was exploring – computer vision technology, detecting a pattern of a face – I really had to ask myself, OK, let’s go back and think not just computer vision right now, but camera technology, in general. And when you look at the ways in which camera technology and particularly film photography was developed, it was optimized for light skin and in particular, the chemical compositions used to expose film used to be calibrated by something called a Shirley Card.

Now, a Shirley Card was an image of a white woman named Shirley. Later on, it – there were others, but it became known as the – a Shirley Card, and that was literally the standard by which the chemical composition would be calibrated. And the issue is that people who didn’t look like Shirley weren’t as well accounted for. And some people might argue, oh, it’s just the limitations of the technology. But actually, when furniture companies complained and chocolate companies complain, I can’t see the difference between the milk chocolate and the dark…

MOSLEY: And the dark chocolate.

BUOLAMWINI: …Chocolate – right? – or the fine grain in my mahogany, they updated the chemical composition. The darker skinned among us got a little bit of a windfall, but it showed that it wasn’t necessarily just the limitation of the technology but a limitation in who was thought worthy of being seen.

MOSLEY: Right. Going back to this mask, I mean, the discovery, Joy, it just floors me because of what the mask represents in our day-to-day lives. I mean, the figurative mask has been used to describe what Black and brown people wear in order to fit the norms or expectations of the dominant culture, and from the very start, this was not lost on you, although you wanted to find a reason that wasn’t social.

BUOLAMWINI: I really did. I was hoping that it was just down to technical issues. And as I was having that experience of coding in the white mask, I really thought about the book “Black Skin, White Masks,” which is talking about the ways in which people change themselves to fit a dominant group, and it – I just didn’t think it would be so literal where I was changing my dark-skinned face to be made visible by a machine, and I thought the last place I would be coding in white face would be MIT.

MOSLEY: You talk quite a bit about the different spaces that you work in and you’ve worked in in technology. Language is very important to you when talking about all of this, especially when we talk about facial recognition technologies. There are two types, right? So there’s facial verification and facial identification. Can you break down the differences?

BUOLAMWINI: Oh, absolutely. So when we’re thinking about the ways in which computers read faces, I’m thinking of a set of questions a computer might be asking. And so first, there’s actually face detection. Is there a face at all? And so the experience I had of coding in a white mask to have my face detected was an example of face detection failure. So that’s one kind of way a computer can analyze a face. Another kind of way a computer might analyze a face is guessing an attribute of the face. So let me guess the age. Let me guess the gender. Some might try to guess ethnicity and others might try to guess your emotion. But like we know you can put on a fake smile, the guess doesn’t mean what is being displayed on the face actually is true to how somebody feels or identifies internally. And then when we get to what’s more technically known as facial recognition, to your point, there are two flavors. So facial verification is also known as 1-to-1 matching. So this is the type of facial recognition you encounter if, say, you’re trying to unlock a phone.

MOSLEY: Right.

BUOLAMWINI: So there’s a face that’s being expected, then there’s a face that’s attempting to have access, and there’s that 1-to-1 match. Now, when we get to facial identification, also known as one-to-many matching, this is when you might think of, you know, “Mission Impossible,” Tom Cruise being detected in a airport among a ton of people. So that’s the surveillance kind of use case. And so one of the things I really tried to do in the book was to walk people through different ways in which AI systems can be integrated into various types of technology, so there’s a deeper understanding when people are hearing about news headlines or new breakthroughs in AI.

MOSLEY: Right.

BUOLAMWINI: So I really appreciate you asking about the nuances between these things.

MOSLEY: Right, because once you started speaking about this – you had a TED talk a few years ago – you started getting a slew of letters from people whose lives were really impacted, in some cases almost ruined. One person wrote you from jail believing that they were locked up because of false facial recognition, there was a false facial recognition match. Can you go into more detail on why something like this could happen?

BUOLAMWINI: Oh, yes. So even after the people who would actually send me letters, there were also new stories. One recent one that sticks with me is the arrest of Porcha Woodruff due to facial recognition misidentification. Porcha was eight months pregnant when she was falsely arrested for committing a carjacking. And I don’t know anyone who’s eight months pregnant jacking cars, you know? So there’s also this question of this overreliance on machines, even when common sense might indicate there could be other alternative suspects.

And to your question, how does it happen? How is it that someone can be misidentified by a machine? So we have to look at the ways in which we teach machines to recognize the pattern of a face. And so the approach to this type of pattern recognition is often machine learning. And when we talk about machine learning, we’re talking about training AI systems that learn from a set of data. So you have a data set that would contain many examples of a human face. And from that data set, using various techniques, the model would be trained to detect the pattern of a face. And then you can go further and say, OK, let’s train the model to find a specific face. What my research showed and what others have shown as well is many of these data sets were not representative of the world at all. I started calling them pale male data sets…

MOSLEY: Right.

BUOLAMWINI: …Because I would look into the data sets, and I would go through and count – right? – how many light-skinned people, how many dark-skinned people, how many women, how many men, and so forth. And some of the really important data sets in our field, they could be 70% men, over 80% lighter-skinned individuals. And these sorts of data sets could be considered gold standards, the ones we look to, to judge progress in our field. So it became clear to me that, oh, the data that we’re training these systems on, and also the data that we’re using to test how well they work, don’t include a lot of people.

And so it’s not then so surprising that you would have higher misidentification rates for people who are less represented when these types of systems were being developed in the first place. And so when you look at people like Porcha Woodruff, who was falsely arrested due to facial recognition misidentification, when you look at Robert Williams, who was falsely arrested due to facial misidentification in front of his two young daughters, when you look at Nijeer Parks, when you look at Randal Reid – Randal was arrested for a crime that occurred in a state he had never even set foot in, right? And all of these people I’ve mentioned, they’re all dark-skinned individuals.

MOSLEY: Let’s take a short break. If you’re just joining us, we’re talking with computer scientist, researcher and poet Joy Buolamwini about her new book, “Unmasking AI: My Mission To Protect What Is Human In A World Of Machines.” We’ll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF JEFF COFFIN AND THE MU’TET’S “LOW HANGING FRUIT”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. And if you’re just joining us, my guest today is computer scientist Joy Buolamwini, founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, an organization that raises awareness about the impacts of AI. She’s written a new book titled “Unmasking AI: My Mission To Protect What Is Human In A World Of Machines.”

There’s something else that your research also found, and I want to get a clear understanding of why this happens, too. Why is it that in some cases, this technology misgenders people with dark skin? This has actually happened to me, I admit, while playing some of those TikTok facial recognition games. It always thinks that I’m a guy.

(LAUGHTER)

BUOLAMWINI: So this was what I ran into after my TED Talk. So I did my TED Talk, you mentioned a bit earlier, and I had my TED profile image. And I was showing the example of coding in a white mask, face detection failure. And so I decided to use my TED profile image and just upload it to the online demos of a number of companies, some well-known companies. And I noticed that some didn’t detect my face, but the ones that did detect my face were labeling me male. And that’s when I started actually looking at gender classification. And as I went and I looked at the research on gender classification, I saw with some prior studies, actually, older women tended to be misgendered more often than…

MOSLEY: Well, there you go.

BUOLAMWINI: …Younger women.

MOSLEY: Yeah.

BUOLAMWINI: And I also started looking at the composition of the various gender classification testing data sets, the benchmarks and so forth. And it’s a similar kind of story to the dark skin. Here, it’s not just the proportion of representation but what type of woman is represented. So, for example, many of these face data sets are face data sets of celebrities. And if you look at women who tend to be celebrated…

MOSLEY: Like…

BUOLAMWINI: …Women who tend to be…

MOSLEY: Yeah. They’re lighter-skinned women.

BUOLAMWINI: Lighter-skinned women, but also fit very specific gender presentation norms and stereotypes, as well. And so if you have systems that are trained on some type of ideal form of woman that doesn’t actually fit many ways of being a woman, this learned gender presentation does not reflect the world.

MOSLEY: Well, in 2019, you spoke before the House on facial recognition technology, and I want to play a clip of House Rep Michael Cloud, a Republican of Texas, asking you about the implications of private companies having access and using facial recognition technology. Let’s listen.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED RECORDING)

MICHAEL CLOUD: You mentioned Facebook in your remarks, and I find that interesting ’cause I’m extremely concerned about the government having this kind of unchecked ability. I would be curious to get your thoughts of corporations having the same sort of ability. And also, Ms. Buolamwini, you want to speak to that?

BUOLAMWINI: Absolutely. So you’re looking at a platform that has over 2.6 billion users. And over time, Facebook has been able to amass enormous facial recognition capabilities using all of those photos that we tagged without our permission. What we’re seeing is that we don’t necessarily have to accept this as the default. So in the EU, where GDPR was passed because there’s a provision for biometric data consent, they actually have an option where you have to opt in. Right now, we don’t have that in the U.S., and that’s something we could immediately require today.

MOSLEY: That was our guest, Joy Buolamwini, answering a question from House member Michael Cloud about private company access to facial recognition technology.

You’ve brought this up time and time again about permissions and opting in, opting out. We’ve seen lots of talk from the White House and really from Congress more broadly about taking steps, but there hasn’t been steps yet to regulate or at the very least, push for an option for people to opt whether they want their images to be used in these larger data sets. What are some of the biggest challenges for you as you talk about this with lawmakers?

BUOLAMWINI: One of the challenges is awareness. Oftentimes, so many of the ways in which AI systems are adopted or deployed are not known until there are issues. I remember the Algorithmic Justice League, we actually did an op-ed about the IRS adopting facial recognition technology for access to basic tax services, and one of the biggest challenges is the narrative of consent versus the reality of coercive consent. And this is what I mean by that. So you go to the IRS website and you’re told that, oh, OK, this is optional unless if you’re creating a new account. OK. So then when you’re creating the new account, they’re saying, OK, your option is to use this third party to sign up. And then if you sign up for the third party and you actually go to their website and you read their conditions, they’ll say, you don’t have to use us, but if you use us, you’re going to waive away your right to a class-action lawsuit. We can’t guarantee you that this technology is going to work.

And so, like, technically, on paper, you don’t actually have to use this, but the reality is a different scenario. And then we get the flip when we’re looking at facial recognition use within airports. On their websites for the TSA, it will say this is an opt-in program. That’s what it says. TSA officers are here to treat you with dignity and respect. That’s what it says on the website. So I go to airports, I travel often, and what I see are agents just telling people to step up and look at the camera.

MOSLEY: But you can actually say – you have to opt into it. You can say no?

BUOLAMWINI: Well, opting in – if we are saying this is opt in, you should be asked if you want to do it. Instead, what you’re being told is to step up to the camera. So what’s meant to be an opt-in process in the way that their policy is written, is actually executed in an opt-out fashion, and many people don’t even know that they can opt out. And in fact, it was supposed to be opt in.

MOSLEY: Our guest today is Joy Buolamwini. Her new book is titled “Unmasking AI: My Mission To Protect What Is Human In A World Of Machines.” We’ll continue our conversation after a short break. I’m Tonya Mosley, and this is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF THE ADAM DEITCH QUARTET’S “ROLL THE TAPE”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. I’m Tonya Mosley, and today my guest is computer scientist Joy Buolamwini, founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, an organization that raises awareness about the impacts of AI. She’s written a new book titled “Unmasking AI: My Mission To Protect What Is Human In A World Of Machines.” Her TEDx talk on algorithmic bias has over a million views, and her MIT thesis mythology uncovered large racial and gender biases in AI services from companies like Microsoft, IBM and Amazon. She serves on the Global Tech Panel, convened by the vice president of the European Commission, to advise world leaders and technology executives on the ways to reduce the harms of AI.

You know, Dr. Joy, I was really struck by how honest in the book you were about – at first, you were hesitant about this idea of being an activist and taking on issues of race within AI and computer science more generally because you were at MIT to create groundbreaking technology. You did not want to be labeled as someone who was taking on issues of race and racism.

BUOLAMWINI: That or sexism or any of the isms, as the work is intersectional. And so when I got into computer science, I wanted to build cool future tech, and that’s what took me to the media lab. I was not trying to deal with various types of isms, and I also understood it would make my life harder, you know, if I needed to speak up about these types of issues. And so my thought was, graduate school is hard enough, you know? Why had the added burden of being that person pointing out the flaws, critiquing everything when we’re out here, just trying to have fun? And…

MOSLEY: Yeah.

BUOLAMWINI: So that was my initial viewpoint until I just saw how harmful these systems could be and who would be harmed, particularly people like me – people from communities of color, women of marginalized identities of many forms. And I realized that I had a platform, I had the skills and technical know-how to do deep investigations of these systems and that maybe, in fact, I did have some kind of duty. And certainly I had the opportunity to say something and have it be heard.

MOSLEY: Even in saying something, though, you were very aware of the perception of you as a Black woman. I was struck by a story you tell in the book. When you started to speak about the coded gaze, you would practice before speaking to an audience. That’s – all people do that. But not exactly what to say – of course, that was very important. But also just as important is how to say it. You didn’t want to come off like an angry, Black woman.

BUOLAMWINI: Oh, yes. I actually remember when I was recording this video for an art installation called Hi Camera, and in that video, I’m having a playful conversation with a computer vision system. And so I’m saying, hi, camera. Can you see my face? You can see my friend’s face. What about my face? That’s not how I initially said it. I said – I was like, hi. Can you see my – what about my friends? But you can’t see my face. And so – because I certainly felt a certain kind of way about the situation.

And so I was wearing my own mask to be heard because I understood that if I were perceived as being angry or bitter, that might block certain people from understanding what I was saying. And understanding what I was saying actually had implications for everybody because no one is immune from being harmed by AI systems. Also, by that time, I had quite a bit of experience navigating as a Black face in very white places. So I also had an understanding from those experiences at how easily concerns can be dismissed because of tone policing and so many other factors. And so part of the strategy was to speak in a way that would allow people to hear me.

MOSLEY: I’ve mentioned a few times that you’re a poet. You call yourself, actually, a poet of code. When did it become clear to you that you could use your poetry to bring meaning to this larger body of work?

BUOLAMWINI: It wasn’t clear. I took – at first, I took a little bit of a risk for me because I spent so much time wanting to have my research be taken seriously.

MOSLEY: You were concerned your poetry wouldn’t seem objective.

BUOLAMWINI: I was concerned people might also think it’s a gimmick. It’s, like, all manner of concerns, yet alone if the poetry is any good, right? So there’s that part, too. And so after I published the “Gender Shades” paper and it was really well-received in the academic world and also industry, in some ways, I felt that gave me a little bit of a shield to experiment with more of the poetic side. And so shortly after that research came out, I did a poem called “AI, Ain’t I A Woman?,” which is both a poem and an AI audit where I’m testing different AI systems out. And so the AI audit results are what drive the lyrics of the poem. And as I was working on that, it allowed me to connect with the work in a different way. This is where the humanising piece comes in.

So it’s one thing to say, OK, the system is more accurate than that system, or, the system performs better on darker skin or performs better on lighter skin. And you can see the numbers. But I wanted to go from the performance metrics to the performance arts so you could feel what it’s like if somebody is misclassified, not just read the various metrics around it. And so that’s what the whole experimentation around “AI, Ain’t I A Woman?” was, and that work traveled in places I didn’t expect. Probably the most unexpected place was with the EU global tech panel. It was shown to defence ministers of every EU country ahead of a conversation on lethal autonomous weapons…

MOSLEY: Wow.

BUOLAMWINI: …To, again, humanize the stakes.

MOSLEY: This is very powerful. And I was pretty moved when I watched a video of you reciting the poem along with those images, which – you say they work in conjunction with each other because this “AI, Ain’t I A Woman?” is a modern-day version of Sojourner Truth’s 1851 speech at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. What has been the reaction in these tech spaces when you read these poems? What’s some of the feedback that you receive?

BUOLAMWINI: The mood shifts. I mean, sometimes I’ll hear a gasp. It goes beyond what a research paper could do, or even just what I could do simply by describing it, because what the evocative audit allows you to do and invites you to do is to be a witness to what AI harm can look like. And so companies have changed even the ways in which they develop their AI systems. And some have pointed to that poem and other work from the Algorithmic Justice League as influencing their choices. So again, for me, it was dipping my toe into the creative space a bit, not quite knowing how far it would travel.

MOSLEY: If you’re just joining us, we’re talking with computer scientist, researcher and poet Joy Buolamwini about her new book, “Unmasking AI: My Mission To Protect What Is Human In A World Of Machines.” We’ll continue our conversation after a short break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF THE BAD PLUS’ “THE BEAUTIFUL ONES”)

MOSLEY: This is FRESH AIR. And if you’re just joining us, my guest today is computer scientist Joy Buolamwini, founder of the Algorithmic Justice League, an organization that raises awareness about the impacts of AI. She’s written a new book titled “Unmasking AI: My Mission To Protect What Is Human In A World Of Machines.”

I want to talk a little bit about solutions because I want to know where you think we are in this push for regulation. I’m thinking about back when cars first made their way on the roads, and there was, essentially, you didn’t need a license, you didn’t wear seatbelts, there were no rules of the road. And it sounds crazy right now, but it was this new technology that was out there, and we didn’t have any of that. And so sometimes I think about that when we’re talking about AI and talking about technical advances, because where are we in this stage of getting to the point of regulation?

BUOLAMWINI: No, I love that car analogy. And I actually heard Professor Victoria Dignum (ph) say it this way at a U.N. convening around AI – right? – saying that AI is at a stage where it’s a car with no safety checks, a driver with no license, roads that haven’t even been paved.

MOSLEY: Right.

BUOLAMWINI: So I don’t think we even have the roads yet, let alone traffic signs, so we are in the very early days when it comes to legislation and regulation around AI. But I will say we are in a very different atmosphere when it comes to the conversation compared to when I started this work in – 2015 is when I started building the Aspire Mirror and 2016 is when I really started doing more of the deeper dive research. And as I write in the book, I would mention AI bias, algorithmic discrimination, and I was sometimes just flat-out dismissed, sometimes met with ridicule.

And so to have the White House release an executive order on AI, to have a EU AI act in its final stages, to have some of the world’s leading companies also acknowledging AI bias, AI discrimination, and AI harm, this seems like the norm now. But it wasn’t so long ago when that was not even mentioned when people were talking about AI, and if it was, it was definitely done in a way that was marginalized. So I think there has been significant progress in terms of prioritizing the need to do something, now there’s that something part.

MOSLEY: What is the something, right? As I mentioned earlier, you met with President Biden this past summer as part of this roundtable with several other experts in this space. What was the most urgent message you were able to impart to him?

BUOLAMWINI: For me it was that we have an opportunity to lead on preventing AI harms. And the subtitle of the book is “Protecting What Is Human In A World Of Machines.” And when I think of what is human, I think about our right to express ourselves, the essence of who we are and our expectations of dignity. So I challenge President Biden for the U.S. to lead on what I call biometric rights. So when I’m talking about our essence, our actual likeness – so right now – and I do various examples throughout the book, as you know. Someone can take the voice of your loved one, clone it, and use it in a hoax. So you might hear someone screaming for your name, saying someone has taken something…

MOSLEY: Right.

BUOLAMWINI: And you have fraudsters who are using these voice clones to extort people. Celebrity won’t save you; you had Tom Hanks. His likeness was being used with synthetic media with a deepfake to promote…

MOSLEY: That’s right.

BUOLAMWINI: …A product, you know, he had never even heard of. And so we see these algorithms of exploitation that are taking our actual essence. And then we also see the need for civil rights and human rights continue. And so it was very encouraging to see in the executive order that the principles from the blueprint for an AI bill of rights such as protections from algorithmic discrimination, that the AI systems being used are effective, that there are human fallbacks, were actually included, because that’s going to be necessary to safeguard our civil rights and our human rights.

MOSLEY: You know, with everything that you talk about, I just keep going back to thinking about this most salient point. You use the term – these are sociotechnical problems. What we are really seeing in AI is a reflection of who we are. So your book is really also asking us to look at ourselves, too.

BUOLAMWINI: Absolutely. And lately, with the adoption of AI systems, at first, I thought we were looking at a mirror, but now I believe we’re looking into a kaleidoscope of distortion. And this is what I mean by that. I was looking at a recent test done by Bloomberg News. They decided to test out text-to-image generation system – generative AI system. And so they put in prompts for high-paying jobs, low-paying job. So CEO, judge, architect. They didn’t look like me, I’ll put it that way, right?

MOSLEY: Yeah.

BUOLAMWINI: And then when you had low-paying jobs – social worker, fast-food worker – then we had some diversity. Some women, too. And then when you put in prompts for criminal stereotypes – drug dealer, terrorist, inmate – that’s where you saw an overrepresentation of men of color. And I was particularly struck by the example of the prompt for judges. And so in the U.S., women make up around 30% of judges. And this particular text-to-image model depicted women as judges no more than 3% of the time. And so this is when I started thinking of this notion of a kaleidoscope of distortion, because the technologies we believe to be bringing us into the future are actually taking us back from the progress already made that in and of itself isn’t yet enough.

MOSLEY: There is this real fear that robots are going to take over the world at some point, that AI is going to essentially be the destruction of humanity. Is that a concern that you have?

BUOLAMWINI: I’m concerned with the way in which AI systems can kill us slowly already. I’m also concerned with things like lethal, autonomous weapons, as well. So for me, you don’t need to have superintelligent AI systems or advanced robotics to have a real harm. A self-driving car that doesn’t see you on the road can be fatal and harmful. I think of this notion of structural violence where we think of acute violence – there’s the gun, the bullet, the bomb, we see that type of violence. But what’s the violence of not having access to adequate health care? What’s the violence of not having housing in an environment free of pollution? And so when I think about the ways in which AI systems are used to determine who has access to health care and insurance, who gets a particular organ, you know, in my mind, there are already – and in, also, the world, we see there are already many ways in which the integration of AI systems lead to real and immediate harms. We don’t have to have superintelligent beings for that.

MOSLEY: What power do everyday citizens have in all of this? – ’cause it feels like, OK, the power is in these big companies and in the government taking steps to push for regulation.

BUOLAMWINI: I truly believe if you have a face, you have a place in the conversation about AI. My own story started with sharing an experience. An experience that felt a bit uncomfortable and was definitely embarrassing, and I wasn’t even sure if I wanted to share it. But in sharing that experience, I realized I was not alone, and it encouraged others to share their stories of being excoded, experiencing AI harm. So I would never doubt the power of your lived experience and sharing your personal story. So as you encounter AI systems, whether it’s in your workplace, maybe it’s in the hospital, maybe it’s at school, you know, asking questions, right? Does this system – why have we adopted this system? Does it actually do what we think it’s going to do?

MOSLEY: Dr. Joy Buolamwini, I really appreciate this conversation. I appreciate your knowledge, and I appreciate this book. Thank you so much.

BUOLAMWINI: Thank you so much for having me.

MOSLEY: Joy Buolamwini talking about her new book, “Unmasking AI: My Mission To Protect What Is Human In A World Of Machines.” Coming up, we listen back to Terry’s interview with former first lady Rosalynn Carter, who will be laid to rest this week. She died last week at the age of 96. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MALACHI THOMPSON AND THE AFRICA BRASS’ “BLUES FOR A SAINT CALLED LOUIS”) Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.