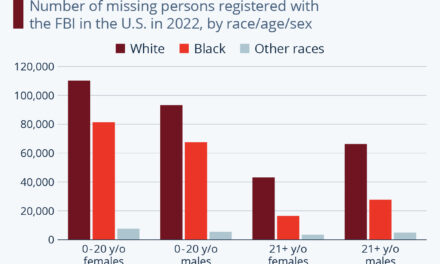

Breast cancer health disparities disproportionately impact Black/African American women in the United States. Black women have a 40 percent higher death rate compared to white women. Strikingly, breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths for Black women, underscoring the need to address this public health challenge.

Mammography screening is considered a critical tool in mitigating disparities. However, Black women experience barriers to screening and are more likely to be diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer at younger ages, and with advanced stage breast cancer.

To address these barriers, researchers from Florida Atlantic University’s Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing conducted a study in a sample of Black women receiving care at its nurse-led FAU/Northwest Community Health Alliance Community Health Center (CHC) in West Palm Beach, which provides services to vulnerable underserved populations. They looked at mammography screening frequency, beliefs about breast cancer including perceived susceptibility, perceived benefits and perceived barriers to screening.

Researchers also conducted a retrospective chart review of mammography screening in the electronic health record (EHR) system of all racial and ethnic minority patients in the CHC, the majority of whom are Black and Hispanic women.

Findings, published in the European Society of Medicine’s journal Medical Research Archives , show suboptimal utilization of annual screening mammograms among low-income Black women and several reported barriers. Almost half reported having annual mammograms; the remainder reported having mammograms every two to three years, and some women never had a mammogram in their lifetime, despite being age 40 or older.

Most Black women had a low breast cancer risk perception; 67 percent reported that it is ‘very unlikely’ that they will get breast cancer in the next five years and 60 percent believed that it is ‘very unlikely’ that they will get breast cancer in their lifetime.

From the medical record review, a total of 392 underserved women between the ages of 40 to 74 were eligible for an annual screening mammogram, with 62.5 percent identified as Black/African American. Only 31 percent had a documented mammogram in the EHR within the past two years.

Interestingly, researchers found that the participants perceived mammograms as very beneficial. Eighty percent believed that ‘if breast cancer is found early, it’s likely that the cancer can be successfully treated’ and 90 percent indicated that ‘having a mammogram could help find breast cancer when it is first getting started.’

“Our findings suggest that Black women actually see the benefits of having an annual mammogram; however, some perceived and actual barriers may be preventing these women from obtaining screening mammograms at the appropriate age,” said Tarsha Jones, Ph.D., senior author and an assistant professor in FAU’s College of Nursing.

Among the top cited barriers reported in the study include: ‘getting a mammogram would be inconvenient for me;’ ‘getting a mammogram could cause breast cancer;’ ‘the treatment I would get for breast cancer would be worse than the cancer itself;’ ‘other health problems would keep me from having a mammogram;’ and ‘not being able to afford a mammogram would keep me from having one.’ However, this underserved population also experience real barriers related to social determinants of health.

“Living in poverty is a substantial risk factor for poor health outcomes because women who are poor do not have discretionary incomes to use as co-pays for health care services. This demonstrates the importance of providing these women with free life-saving mammograms,” said Jones.

About 47 percent of the population in West Palm Beach live below 200 percent of the poverty-level; more than 20 percent are uninsured. Nearly 27 percent of the women in the study were uninsured at the time of the survey, 16.7 percent were unemployed and 13.3 percent were disabled, indicating the vulnerability of this population.

“People in poverty often lack health literacy and access to resources needed to develop sustained care partnerships essential for their long-term health and well-being,” said Karethy Edwards, Dr.PH, APRN, co-author, the John Wymer Endowed Professor in Nursing and executive director of the CHC. “Our Community Health Centers are strategically located in medically underserved areas to provide comprehensive care services to any individual who walks through the doors regardless of their ability to pay.”

Black women are more likely to be screened for mammography at non-accredited facilities located at safety-net hospitals in minority serving communities.

“Perceived barriers to and beliefs about mammography screening should be taken into consideration when designing interventions to increase breast cancer screening in Black women,” said Karen Wisdom-Chambers, DNP, APRN, co-author and an assistant professor in FAU’s College of Nursing.

To respond to the breast health needs of underserved women and to mitigate access to care barriers, a patient navigator, supported by the Promise Fund of Florida, has been added to the health care team at CHC to identify, guide and support eligible women through the breast cancer screening process in a timely manner. Additionally, women with abnormal mammograms or those who are diagnosed with breast cancer will receive timely follow-up services and referrals for treatments. The patient navigator also participates in community outreach to increase awareness about the optimal age to start breast cancer screening and to emphasize the lifesaving benefits of early detection. Patient navigation is an evidence-based intervention approach that has been shown to improve breast cancer outcomes by reducing barriers to health care.

“Our team is now working to evaluate the outcomes and effectiveness of patient navigation in reducing the barriers uncovered in this study; our ultimate goal is to save lives and to reduce cancer health disparities,” said Jones.

Study co-author is Katherine Freeman, Dr.PH, leader of the Biostatistics Collaborative Core in FAU’s Division of Research and a professor of biomedical science in FAU’s Schmidt College of Medicine.