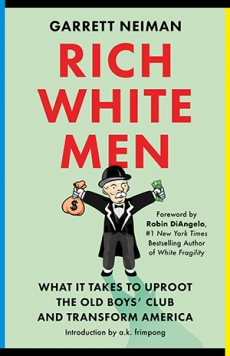

Rich White Men: What It Takes to Uproot the Old Boys’ Club and Transform America

Garrett Neiman

384 pages, Legacy Lit, 2023

Since 1980, annual charitable giving in the United States has tripled in inflation-adjusted dollars. It will soon eclipse $500 billion. Yet during the same period—a period in which America’s wealthiest 1 percent became $28 trillion richer—the bottom half didn’t get any wealthier.

Through my experiences as a nonprofit entrepreneur and social justice activist, I’ve come to see how part of what explains this conundrum is a collection of myths that justify inequality. Many of the rich white men I know believe in and traffic these myths as conventional wisdom. I feel a responsibility to name and challenge these myths because, earlier in my life, I believed every one of them. That is among the main reasons why I wrote Rich White Men, which shines a light on how elite bias and behavior perpetuates inequality, on why we are all better off in an equitable America, and on the brave few who are charting a different path forward.

The excerpt below challenges one of these foundational myths: The notion that wealthy and elite-educated white men like me have earned all of our power. I confront this myth by introducing a new term, “compounding unearned advantage.” The excerpt concludes with some action steps that the advantaged can take to help construct an equitable America.

I hope Rich White Men helps to make visible what is available to wealthy white men who aspire to engage equitably. I also hope it is a useful resource for less wealthy white men, white women, and people of color who are working to influence the rich white men whose power seeps into our daily lives and news cycles.

There is perhaps no sector where those capabilities are more needed than in philanthropy, which aspires to reduce inequality but so often has the opposite effect.—Garrett Neiman

I’ve come to think of the life-changing impact that occurs when unearned advantages intervene at key moments in our lives as “compounding unearned advantage.” Similar to compound interest, the unearned advantages people inherit gild their paths and shut other people out. When those with advantaged identity markers receive better treatment from teachers, police officers, doctors, professors, hiring managers, bosses, sponsors, politicians, and others who have power to bend their trajectories, even small unearned advantages can swell into great advantages.

Compounding unearned advantage says nothing about how hard any individual works or the quality of their choices. Rather, it simply acknowledges that those who benefit from unearned advantages receive a premium on their positive efforts and a discount on their missteps. And the basics of compound interest dictate that even a slightly higher return compounds into great advantages over time. The compounding nature of unearned advantage is the reason even the most subtle negative stereotypes and unconscious biases have massive pernicious effects.

If there’s one thing that rich white men know like the back of their hand, it’s compound interest. When I was a kid, my dad taught me the rule of seventy-two, which is a way to estimate the number of years it takes for an investment to double in value. The way the rule of seventy-two works is that you divide seventy-two by the rate of return you’re getting on your investment. For example, an investment with a 5 percent annual return will double every fourteen years (seventy-two divided by five is about fourteen). By contrast, an investment with a 10 percent annual return will double twice as fast—every seven years. Over time, the differences compound. For example, a $10,000 investment with a 5 percent rate of return will be worth about $100,000 in fifty years. How much would that same investment be worth with a 10 percent rate of return? $1.2 million. Each incremental increase in annual return fuels an exponentially different outcome.

Unearned advantages have compound effects, too. When someone benefits from ongoing unearned advantage—because of their gender, race, socioeconomic status, or other identity characteristic—the unearned advantages compound and cause trajectories to diverge.

One of the ways that compounding unearned advantage manifests is that it impacts career trajectories within institutions. In most companies and organizations, those who have advantaged identity markers are promoted at higher rates. When the “promotion game” is repeated sequentially, those who have advantaged identity markers increasingly benefit from compound effects. Say, for example, that the odds of a white man being promoted in a company at each level are one in two and that the odds of a Black woman being promoted in a company are one in three (many companies aren’t so equitable). When these different rates compound, the person benefiting from unearned advantage becomes more and more likely to climb the ladder. If the promotion game is played ten times over a career, the white man is fifty-seven times more likely to reach the top post than the Black woman. That result reflects our present reality: just forty-four Fortune 500 CEOs are women, and just three are Black.

I wasn’t always aware of the ways unearned advantages have helped me get ahead. Initially, they felt invisible to me. But over time, I’ve listened to enough stories from people whose lived experience is different from my own to see how compounding unearned advantages have shaped my trajectory as a wealthy white man.

I was struck one day when Julie Lythcott-Haims, an American educator and author, described to me her experience with her elementary school’s gifted and talented program.

Julie is a Black woman from a mixed-race family. When Julie asked to be tested for the gifted program, her school refused. Julie’s continued persistence only led her white male principal to dig his heels in further. Only when Julie’s enraged white mother came to the school did he ultimately acquiesce. When Julie finally was tested for the program, she scored in the 99th percentile. Students had already been slotted into classes by the time Julie received her results, so Julie joined late. On her first day in the gifted program, the principal introduced Julie to her classmates in a way she will never forget: “Looks like anyone can be in ‘gifted’ if you have a parent who complains,” he loudly told the entire class.

My experience with my school’s gifted program was entirely different—but it, too, is seared into my memory. To be sorted as gifted and make it into the Gifted and Talented Education (GATE) track, I needed to surpass the 90th percentile on the second-grade gifted exam. GATE students received extra attention from the best teachers, and that advantage compounds. GATE was the gateway to a top university—and a better life.

The test’s math and reading questions came easily to me, but I felt lost during the spatial portion. A few weeks later, my mom and I opened the results. I scored in the 87th percentile. It was close, but I didn’t make the cut. I was devastated.

I was just starting to process the experience when I learned that my teacher had approached my mom with a proposition. There was a possible workaround: according to school district policy, teachers can submit a portfolio to the district on behalf of a student and request that student to be admitted into the gifted program. Even though I hadn’t passed the exam, she felt I was a high-potential student who deserved to be in the gifted program, so she told my mom that she wanted to recommend me via the alternative process. It required significant time and paperwork, but ultimately, I was labeled “gifted.” And I’ve been on the “gifted” track ever since.

That credential put me on the accelerated track and then the Advanced Placement (AP) track, prerequisites for my admission to Stanford. Stanford provided the credentials and network that got me to Harvard for two graduate degrees and empowered me to start three nonprofits.

At the time, I felt my teacher’s advocacy had righted a wrong. I felt I was gifted—my test scores just didn’t reflect my potential (heard that one before?). Today, I acknowledge that it’s more complex than that. How was I different from an equally intelligent student in a high-poverty neighborhood whose teachers may have been too overwhelmed to offer such advocacy? How could I account for the fact that—as Johns Hopkins researchers found—white teachers like mine believe white students have more potential? Or the analysis of former Google data scientist Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, who found that in their Google searches parents are two and a half times more likely to ask “Is my son gifted?” than “Is my daughter gifted?” which suggests that many parents see their sons as more intelligent or are more invested in their sons’ being intelligent because intelligence typically offers more status and financial rewards for men than it does for women.

It is true that if the GATE test had included just the math and verbal sections—without the spatial component—I would have passed with flying colors. So the issue is not necessarily whether I had gifts—I believe every child has gifts—but rather that an assessment was made to label me “gifted” even though I didn’t meet the criteria that other children were asked to meet.

Since the advantaged can sometimes game the system, gifted programs have perpetuated an educational caste system within public schools. Similar to how white flight in the 1960s whitened suburban schools and effectively reinstituted segregation, gifted programs whitened classrooms within schools. And as elite university admissions have become more competitive, many wealthy parents now spend thousands of dollars not only to help their teenagers succeed on the SATs but to ensure their elementary school–age children meet eligibility requirements for gifted programs.

Unequal access to gifted and talented programs is among the many ways that the playing field favors rich white men. Any of the unearned advantages that worked in my favor—growing up in a wealthy community with well-resourced public schools, having white teachers who believed in my potential, having a gender many parents associate with intelligence—could have been enough to shift my trajectory. But with all three in play, that outcome was exponentially more likely.

Compounding unearned advantage is about more than opportunity; it’s about surviving in a violent America that prioritizes individualism over collective safety. I suspect that’s why many of those who lack a single advantaged identity marker—such as wealthy white women, wealthy Black men, and low-wealth white men—have told me that they feel oppressed. Nothing protects wealthy white women from sexual assault in a society that allows rape kits to collect dust and leaves rapists unaccountable. Nothing protects wealthy Black men from police officers and rogue vigilantes who can murder without consequence. Nothing protects low-wealth white men from the violence of poverty, which kills 874,000 Americans annually, more than cancer.

Yet still, unearned advantage can be a shield in a violent world. It’s not easy being a wealthy white woman in a male-dominated society, but the compounding unearned advantages of race and class offer some protection. It’s not easy being a wealthy Black man in a white-dominated society, but the compounding unearned advantages of gender and class offer some protection. It’s not easy being a low-wealth white man in a wealthy-dominated society, but the compounding unearned advantages of gender and race offer some protection.

When I heard about the white woman who threatened to send police after a Black bird-watcher in Central Park in 2020, I was angry. And I was angry at the white male Lyft driver I met in Cincinnati who spent the entire drive spewing racist and xenophobic views about people of color in his community. But I also wondered: If I were underneath the weight of patriarchy or poverty—or both—would I try to hang on to my unearned advantages for dear life, too?

And if I’m honest, there are still instances when I leverage my unearned advantages to make my life easier or advance my own agenda—like when I asked a wealthy white couple if I could borrow their lake house for a month rent-free so I could write under ideal conditions.

I imagine that people from marginalized backgrounds are sick and tired of rich white men claiming that they have earned everything they have when it is far more complicated than that. In those moments when we succeed, we can feel proud to have risen above the crowd. But we can still acknowledge the inconvenient truth that most people have been shut out of the game we’ve been playing.

We don’t need to feel guilty or fragile about that. I can feel secure about who I am as a person my contributions without feeling like I fully earned every accolade and success.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed,” writer and activist James Baldwin once said. “But nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Acknowledging the truth about compounding unearned advantages will do more to set us free than any lie we tell ourselves ever could.

Five Actions the Advantaged Can Take to Help Construct an Equitable America

1. Learn more about your ancestral roots, both the hardships they endured so you could have a better life and how they may have been complicit in or directly involved in upholding an unjust system. If your ancestors enslaved people, reach out to Lotte Dula for guidance about processing that experience and making amends. If they had a connection to spirituality, learn more about why that connection was important to them and consider restoring any aspects of that connection that you’ve previously lost.

2. Conduct a family equity audit. Add up the hours that everyone spends on household responsibilities (e.g., childcare, animal care, chores, finances, planning, etc.); then discuss as a family whether responsibilities are allocated equitably and what changes might be made. Make a list of service providers (e.g., nanny, house cleaner, grocery delivery, Uber, etc.); pay them all significantly more, to try to account for the fact that the “market wage” is unlikely to be the wage such workers would accept if America’s systems were not oppressive.

3. Join an organization that equips advantaged people to work in collaborative solidarity toward social justice (e.g., Liberated Capital, Liberation Ventures Men for Equity and Reproductive Justice, Movement Voter Project, Patriotic Millionaires, Resource Generation, Showing Up for Racial Justice, Solidaire Network). If you’re a white man, also join an organization that supports that demographic (e.g., Breaking the Mold, Organizing White Men for Collective Liberation, Support Genius, White Men for Racial Justice).

4. Join your institution’s diversity, equity, and inclusion committee. Build trusting relationships across differences, practice both the “listen and support” and “leverage your advantages” approaches, and periodically ask colleagues from marginalized backgrounds whether you’re striking that balance effectively. Encourage your institution to compensate individuals from marginalized backgrounds who are leading that work.

5. Divest from concentrated wealth and wealth accumulation. Think critically about the level of assets that your family truly needs; then, explore what it’d take to halve that figure. If you already have more than you need, make a plan to give the rest away. If you are involved with any grantmaking foundations, encourage those institutions to spend down their resources over a fixed period of time, instead of existing in perpetuity.