The main hypothesis of this study proposes that exposure to community violence acts as a significant risk factor for a higher prevalence of common mental disorders in adolescents. The main results showed that adolescents living in regions with higher rates of the three types of violence were more likely to have CMDs, with ORs ranging from 2.33 to 2.99. The greatest effect was observed for crimes against properties. Since this type of crime is more common and the proportion of people with CMD is fixed across the analyses for all types of crimes (i.e. the same study population), it is reasonable that the proportion of CMD positive people exposed to higher levels of this crime indicator is slightly higher than for other less common types of crime. Thus yielding a slightly higher effect size estimate.

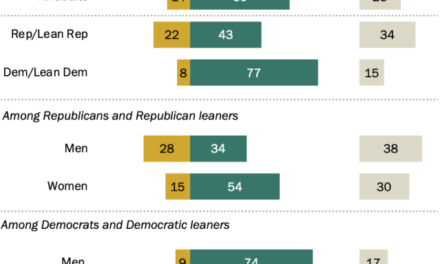

An additional hypothesis was that older, girls, and black adolescents encounter an even greater risk compared to their peers. The results also confirmed this—when stratified by sex, age and race, it becomes clear that the older, the girls, and the black adolescents have higher risks of CMD than their counterparts.

Regarding the first finding – adolescents living in regions with higher rates of violence have higher chances of CMD, no consensus has been established in the literature regarding the association between exposure to CV measured by crime indices and the mental health of adolescents. Two studies conducted in Colombia found positive associations for some outcomes but not for others. The first study, which was performed by Vellez-Gomez, classified regions (communes) based on homicide rates and divided the outcome (depression) into subscales, with a greater likelihood of feelings of ineffectiveness (one of the subscales of the instrument used to measure depression) for adolescents aged 10 to 12 years exposed to high levels of violence; however, the same was not observed for other symptoms of depression [23]. The second study, which was conducted by Cuartas & Roy, evaluated the likelihood of posttraumatic stress disorder and CMDs by comparing adolescents living in high- and low-crime regions through the construction of geospatial indices that considered homicide, and the authors found positive associations between increased exposure to violence and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and CMDs [24].

On the North American continent, Gepty revealed an association between living in more violent regions and depressive symptoms. However, such conclusions pertained only to adolescents who presented rumination, i.e., a pattern of persistent thoughts related to past events and difficulties in life, as a psychological coping strategy. These authors used as exposure variable the rates of violent crimes, such as homicide, rape and armed robbery, and compare with the rates of nonviolent crimes, such as theft and simple robbery [25]. Grinshteyn studied the association of exposure to violence (homicide, armed robbery and rape) with mental disorders in adolescents using two measures of exposure: direct questions presented to adolescents and criminal statistics. The results indicated a positive relationship only for depression, with a lower magnitude when incorporating the criminal statistics than when incorporating direct victimization suffered by the adolescent [26]. Goldman-Mellor used the same crime rates as a previous study and found no association between living in regions with higher crime rates and psychological distress [27].

The lack of standardized community violence rates presents a challenge in the comparison of studies. Consequently, the formulation of crime rates, encompassing not only homicide rates but also broader crime categories, could offer a potential solution to enhance the comparability of future studies.

Regarding the second finding of this investigation, the heightened risk magnitude for girls in developing CMDs subsequent to exposure to the three types of violence when compared to boys, we can conclude that sex operates as an effect modifier in this association. This result is consistent with some results reported in the literature. When studying the associations between CV and anxiety and depression in adolescents, Bacchini analyzed the difference between sexes and observed that girls had a higher likelihood of developing associated symptoms than boys [28]. Boney-McCoy found similar results for symptoms of sadness and posttraumatic stress [29]. Haj-Yahia and Foster also found that girls who were victims of CV were at a higher risk of developing CMDs; however, this finding was not confirmed for adolescents who were witnesses of violence [30, 31]. Other authors found no differences between sexes [32,33,34]. As discussed previously, a possible factor that may explain this finding is the sexist culture during the upbringing of children and adolescents, which encourages boys since early childhood not to expose their feelings, while on the other hand, girls are encouraged to be caretakers of the family and home and to not become involved in conflicts and fights [35, 36]. This is a hypothesis for this finding, we understand that more studies are needed to evaluate sex as an effect modifier, as well as studies of qualitative methodology that can study the hypothesis raised in more depth.

Regarding the third finding, that older adolescents (15 to 17 years old) had a higher risk magnitude of having CMDs than younger adolescents (12 to 14 years old) for the three types of violence studied, we concluded that age was an effect modifier in this study, although the literature is inconsistent about his findings. When performing a meta-analysis evaluating the risk of developing mental disorders related to CV exposure, Fowler found a difference regarding to age; children, adolescents, and young adults were considered, and the risk was higher for adolescents (12 to 25 years) than for children (less than 12 years) [9]. Other reviews have shown few studies that analyzed age as an effect modifier in this association, and the results were limited and conflicting, with some suggesting that younger children are more vulnerable to exposure to environmental risks and others suggesting greater vulnerability for older adolescents [5, 10]. Therefore, studies with large samples that analyze a broader age group of adolescents may strengthen the literature in this topic. One possible explanation for our results is that older adolescents spend more time in the city and experience greater exposure to CV than younger adolescents.

Regarding the fourth finding, that black individuals had a higher risk magnitude of having CMDs than non-black individuals after exposure to high levels of CV for the three types of violence studied herein, we concluded that race was an effect modifier in this study. These results are of fundamental importance because despite the large difference between black individuals and white individuals among victims of CV, with young black individuals being predominantly affected [18], few studies have analyzed whether race has a health-modifying effect on the relationship between violence and adolescents’ mental health. A systematic review, carried out by Miliauskas and collaborators, evaluated studies that addressed the association between community violence and internalizing symptoms in adolescents and found that of the 42 analyzed studies, only 2 tested race as a modifier of the effect of the association, and one of them found that black adolescents were more likely to have internalizing symptoms than their white peers [37]. Another study, conducted for Chen and collaborators, found higher levels of depression and delinquency among black adolescents than among white individuals exposed to moderate levels of CV; notably, this effect was not observed with exposure to high levels of violence [38]. The authors attribute this finding to the desensitization hypothesis, where repeated and continuous exposure to CV leads to a decrease in emotional response to it [39]. The same effect occurs for young Latino individuals compared to white individuals, suggesting that desensitization is present in other ethnic minorities. In a meta-analysis performed by Fowler [9], race could not be tested as an effect modifier due to an insufficient number of studies with ethnically diverse samples; most of the samples were composed of young black individuals, which complicated such an evaluation, which reinforces the need for studies that encompass heterogeneous samples in terms of race, aiming to examine the extent which this characteristic impacts various health-related aspects. Therefore, the present study included a heterogeneous sample, with national representativeness and a composition of 56.4% black individuals and 43.6% non-black individuals.

Some studies emphasize the experience of black individuals with regard to CV. Borowsky studied a sample of approximately 20,000 adolescents who answered a question about fearing an early death (before age 35), with 25.7% of black individuals answering yes but only 10.2% of white individuals answering yes [40]. When analyzing forms of protection for the black population, Henry studied the effect of maternal support through positive reinforcement of the black culture on protecting the mental health of black adolescents exposed to CV. The results showed that such support was a protective factor for depressive symptoms in the studied sample [41].

An important consideration that can influence our results is the hidden figures not included in crime indices. These hidden figures are understood as the number of crimes not reported to the government. Caetano et al. conducted a study using data from the National Household Sample Survey (PNAD) of 2009, collecting information directly from the interviewed individuals regarding being victims of theft, robbery or physical aggression in the last year and whether the incidents were reported to the police. The results indicated a hidden number rate in Brazil of 62.55%; in the state of Rio de Janeiro, the average rate was 63.19% for three types of crime (57.12% for robbery, 69.37% for theft and 65.61% for physical assault). Through probit regression, sociodemographic factors were associated with hidden figures for robberies and thefts; the rates were found to be higher for females, people with lower education levels and younger age groups. Therefore, the crime indicators constructed in this study are likely to be significantly higher than those measured through criminal records [42], which means that our indicators are possibly underestimated, as well as the results of the associations, and the reality could be much worse. And as pointed out in this paragraph and the next ones, underreporting is greater in some territories and populations, such as for black residents of favelas and women.

As pointed out by Casseres, favelas are territories where the state is almost always unable to guarantee its sovereignty and enforce constitutional order, and this absence is often filled by individuals involved in the illicit drug trade and militias. The author indicates that racism arising from the continuing legacy of the colonial-slave model established in Brazil is currently perpetuated in institutional mechanisms through which the state acts on black people [43]. Therefore, hidden figures can be inferred to be even higher in neighborhoods with favelas. This situation is extremely common given that for this population, police records are even less thorough, which is consistent with the results presented in the study by Caetano et al. [44]. The facts presented do not invalidate the results but reinforce the need to evaluate them from the perspective of unequal underreporting, which may represent an even greater effect of CV among black adolescents and favela residents.

Finally, we address the issue of homicides perpetrated by the police. Brazil has a high rate of homicide caused by the state, which is concealed under the guise of acts of resistance, a specific procedure for recording the deaths of civilians resulting from police actions [45]. Thus, homicides committed by police in 2014 were not recorded in the form of intentional homicides and were therefore not included in the crime count for the construction of the lethal crime indicator. Zaccone analyzed archived lawsuits related to records of resistance in the period from 2003 to 2009 in the city of Rio de Janeiro and observed that 75.6% of the records of resistance occurred within favelas; additionally, among the 368 victims, 78% were brown and black, with a mean age of 22 years [46]. Since 2017, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights has ruled that the term “auto de resistance” should no longer be used and should be replaced by personal injury or homicide resulting from police intervention [47]. In 2020, in the state of Rio de Janeiro, 1,245 deaths were attributed to this cause [17]. Therefore, the lethal crime indicator may not reflect the actual total number of deaths in neighborhoods, especially in neighborhoods composed of favelas; these deaths are underestimated, again supporting the hypothesis that the damage to mental health is greater for adolescent black individuals living in favelas, who are the predominant victims of these crimes.

The main strength of this study is the measurement of exposure to CV. Measuring this variable through the creation of crime indices has some advantages, such as the elimination of respondent bias. This bias could have occurred when an adolescent provided information about his or her exposure to violence and mental health because the former can change how he or she perceives the environment and how he or she reacts from an emotional point of view [47]. The classification of these indicators based on the types of crime, which were divided into crimes against property, non lethal crimes, and lethal crimes, can also be highlighted as an advantage because such a strategy allows the investigation of different constructs and intensity levels that may have different effects on adolescents’ mental health. The indicators in this study have the advantage of accounting for the addresses of the sites of the crimes for their construction; homicide rates, for example, were constructed from the victims’ places of residence. Another strength of this study is the location, i.e., the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, which has high rates of violence but few studies of this context.

Losses from and the selectivity of the georeferencing process were limitations because these losses were higher in less urbanized neighborhoods and for adolescents with irregular occupations and a lower SES [48], possibly leading to underestimation of the results. A second limitation is the difficulty of measuring the exposure variable, with the neighborhood serving as the unit of analysis. The municipality of Rio de Janeiro, as well as other municipalities in Brazil, has marked variability in housing conditions within some neighborhoods, with slums and upper middle-class housing in neighboring territories. Thus, the indices for some neighborhoods with high crime rates in a given region may have been mitigated because of less violent regions within the same neighborhood. A third limitation is the relatively high rate of missing data for social class. Many adolescents do not know how to properly inform some of the questions used to create the indicator of social class variable such as education of the head of the family, causing a greater number of missing data. It was not possible to impute this data, which is a limitation of the study. Another limitation in our study is that further neighborhood characteristics, such levels of education, income, and unemployment could be potential confounders, but data was not available. The use of data from different sources, such as the CPSRJ and the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) and IPP, may have generated some degree of inaccuracy when the data were combined; however, this issue was partially circumvented by interpolating population estimates for the same year of data collection, obtaining criminal records for this same period, and then standardizing the rate indices. Last, because this is a cross-sectional study, causality cannot be attributed to the association between CV and CMDs, and this relationship may be bidirectional.

Final considerations

This study provides important contributions to the field of public health, as it reveals new information on the influence of CV on the mental health of adolescents. Among the main findings are the greater likelihood of CMDs for adolescents living in violent regions who experience both crimes against property and crimes against people, as well as the greater vulnerability of girls, older adolescents and black populations.

Given the high rates of violence globally, which are even higher in low- and middle-income countries, knowing the effects of violence on adolescents is critical to prevent and treat CMDs in this population. There is a pressing need for additional studies that delve into the roles played by race, gender, and age, particularly in regions characterized by elevated violence rates. Such research is essential for identifying the most susceptible demographic groups, thereby contributing to the formulation of effective public policies.