For Amoako Boafo, the best part of success is sharing it with his community, those who inspire him, and bringing along as many people as he can on his journey.

This past March, the Ghanaian artist had his New York solo debut with the mega-gallery Gagosian. Boafo, who is known for finger-dipped paintings depicting himself and Black people from Africa and its diaspora, said he’d received praise for the show, but he came out of the experience feeling as though something was missing.

“I was happy with the [reception] and how it turned out, but not having the family or people that I work with to enjoy the paintings as well—for me, it wasn’t enough,” Boafo said in an interview with ARTnews, speaking from Vienna, where he is based. He wanted to find a way for “family to be able to be part of the conversation.”

His solution was to bring some of the pieces from the show this May back home to Accra. The show, which closed earlier this month, featured these works, as well as some new ones, at dot.ateliers, the art space he founded in 2022 that also hosts residencies and maintains an art library and studios.

“It’s important that the people that I make the painting for or with should have access to the painting,” Boafo said. “And also, for them to be part of the experience.”

Held in collaboration with Gagosian, Boafo’s dot.ateliers show is being billed as the first time that a Western commercial gallery has hosted an exhibition with an African artist on the continent.

Andrew Fabricant, chief operating officer of Gagosian, said that the Accra exhibition was borne out of Boafo informing the gallery of his decision not to sell one of the paintings in the New York show—with the intent to show it at an upcoming exhibition at his foundation in Ghana. They both thought it’d be a great idea to create some new works in addition to the particular painting, with Gagosian sponsoring the show alongside Boafo’s foundation.

“Too often, it’s been the case for almost all artists coming out of Africa recently. They get taken out of Africa and they get shown in the West, but there’s never any reciprocity, so we thought it was a great idea,” Fabricant remarked. “There was a huge audience in Accra, of course, so it was an idea that came about very easily, and it’s been very, very successful.” (At the moment, Boafo isn’t formally represented by Gagosian, but Fabricant shared that they are planning another show.)

Boafo’s quest to show his work in Ghana attests to his dedication to his home country, which tends to get lost in discussions of his art, the prices for it, and his celebrity. Rather than coasting by on fame, Boafo is using his star power to support Ghana’s art scene.

Amoako Boafo’s dot.ateliers show, “what could possibly go wrong, if we tell it like it is.”

Photo Nii Odzenma/Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

dot.ateliers is providing resources and access to opportunities for up-and-coming and emerging artists like Crystal Yayra Anthony, Zandile Tshabalala, and Dzidefo Amegatsey through its residency program. Yet even beyond that space, Boafo is leveraging his status to help other Ghanaian artists, like his friend Otis Kwame Kye Quaicoe, whose representation with Roberts Projects was made possible in part because Boafo encouraged him to spend some time in Los Angeles, away from his Portland, Oregon, base, so he could connect with more art world stakeholders.

“My feeling is, from the first time I met Amoako, he’s the kind of person that shares his success. Meaning if he’s successful, more people around him become more successful,” said Bennett Roberts, cofounder of Roberts Projects, which has represented Boafo since 2018. “This is a very unique character trait. I learned from the very beginning that he is a very particular person who does not want everything for himself.”

A Rise Abroad

Before he became a superstar artist, Boafo was a ball boy at the Accra Lawn Tennis Club, then a tennis player. Born in 1984 in the Ghanaian capital, he fostered his interest in art mainly on his own.

Boafo, who lost his father at a young age, taught himself how to paint at home while his mother worked as a cook. As a teenager, he loved drawing and painting, partaking in competitions to sharpen his skills, even though the possibility of career success in the field was low—something that some of Boafo’s peers have spoken of, referring to the lack of a commercial art infrastructure in Ghana.

He was ultimately offered a scholarship by a man his mother worked for, leading to his studies at the Ghanatta College of Art and Design. In a sign of what was to come, he won Best Abstract Painter of the Year in 2007 and Best Portrait Painter of the Year in 2008, his final year at the school.

In 2014, he relocated to Vienna with the Austrian artist Susanda Mesquita, whom he met in Accra and who is now his wife. The year before, the couple cofounded WE DEY, a platform for and by artists of color and under-represented communities.

Boafo went on to pursue an MFA degree at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Attempts to further his practice in the country were met with roadblocks, partly because of his race. Those experiences led him to create “Body Politics,” a series largely credited with being his first mature grouping of works. One painting in that series shows the artist holding the book The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon’s 1961 treatise about the dehumanization effects of colonialism on individuals and nations. Because of “Body Politics,” Boafo was discovered on Instagram by American painter Kehinde Wiley, who bought some of his works and put forward Boafo’s name to some of the galleries representing him, including Roberts Projects.

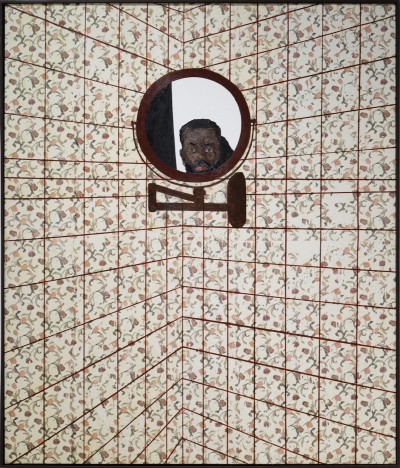

Amoako Boafo, Tulip Tiles, 2023

©Amoako Boafo/Photo Nii Odzenma/Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

Roberts and his team there reached out to Boafo, later organizing his first exhibition in the United States, “I See Me,” in 2019.

Later that year, Boafo was named the first artist-in-residence at the Rubell family’s newly reopened private museum in Miami. That residency program is closely watched because it often jumpstarts the careers of young artists—other past participants have included Sonia Gomes and Cy Gavin—and the Rubells proved prescient once more with Boafo.

But widespread success did not come instantly. In a 2020 Artsy interview, Boafo said, “If I get museum placement and shows, I am guaranteed longevity.” He made that remark in May of that year. Seven months later, in December, one of his paintings sold at auction for more than $1 million. The year after, his art appeared on Dior’s clothes, and was even sent into space by Jeff Bezos.

Boafo’s success means that at any given time, he is travelling or engaging with people around the world, but he always has the continent in his sight and thought.

“I think everything that I will do in the West, I will try my possible best in my small way to bring it back home,” he said.

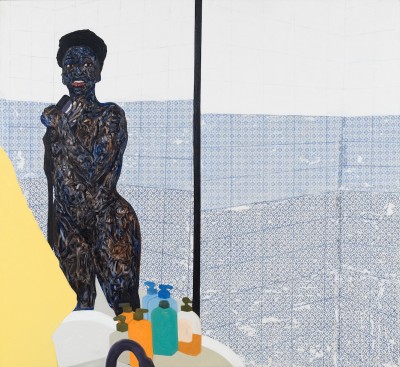

Amoako Boafo, Shower Song, 2023.

©Amoako Boafo/Photo Robert McKeever/Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

‘It’s All About Sharing’

Boafo’s first museum survey, curated by ARTNOIR cofounder Larry Ossei-Mensah, opened at the Museum of African Diaspora in San Francisco in 2021, two years after they first began discussing it. The exhibition, which features works made starting in 2016 and also formerly appeared at the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, is still traveling; it is now on view at the Seattle Art Museum; after that institution, it will head to the Denver Art Museum. According to Ossei-Mensah, the point of the show—titled “Soul of Black Folks,” after a W. E. B. Du Bois book—was to offer a context for Boafo’s work that went beyond the market.

Boafo’s work “was assessing Black lives through his lens, whether it was people he met during his time in Vienna, whether it’s people in Ghana—people that he admired,” said Ossei-Mensah, who first met Boafo in the late 2010s. “So I was trying to use this exhibition as a platform to kind of understand: Why has he been able to cut through all the fads, all the noise? And he’s been able to create a sustainable practice that’s inspiring a new generation.”

Part of Ossei-Mensah’s purpose was to show how Boafo has centered the narratives, stories, and bodies of Black people. Bennett Roberts, the Roberts Projects cofounder, said that Boafo’s portraiture was likely to stand the test of time.

“I think [Boafo] is making paintings that would hold up next to the most important paintings in history. That’s just my opinion—I am sure people will think that I’m foolish for saying that, but I believe that with all my heart,” Roberts said. “The reason is because he is able to capture a portrait of someone that is the essence of that person, not necessarily that person.”

Boafo’s focus on people has extended beyond his art. He’s provided financial support to organizations such as Black Girls Glow, an Accra-based feminist nonprofit that supports women artists. The poet Poetra Asantewa, the organization’s founder, noted that Boafo’s donation “made a huge difference,” allowing it to expand a residency program beyond just Accra-based artists. “It meant that there were people from different backgrounds even within Ghana who were also present,” she said.

The artist himself seemed focused on giving back. “That’s how I want people to remember me,” he said.

His next goal is to get his traveling survey to come to Africa. “It’s always important to have my paintings be in spaces where more people can experience them,” Boafo stated, adding, “Obviously, I will want that show to end somewhere on the [African] continent, which I’m still thinking about. I haven’t found the space yet. For me, it’s all about sharing.”