Your trusted source for contextualizing the news. Sign up for our daily newsletter.

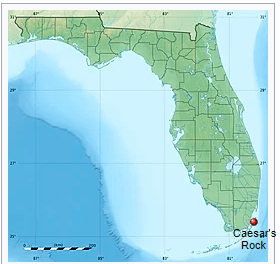

A shooting Saturday at a Dollar General in Jacksonville, Florida — where a White gunman fatally shot three Black people in what authorities are calling a racist hate crime — is drawing attention to policies in the state, particularly around education, that Gov. Ron DeSantis’ critics say have created a hostile climate for Black Americans.

The scene near the store this week has become a familiar one in the United States, a global leader in firearm deaths. Planks of wood bearing the victims’ names — Angela Michelle Carr, 52; Anolt Joseph Laguerre Jr., 19; and Jerrald Gallion, 29 — were bolted together to form crosses.

Mourners, some kneeling in grief, have left candles, teddy bears and flowers at the makeshift memorial in Jacksonville’s mostly Black New Town neighborhood. Among those grieving were survivors of the shooting by a 21-year-old who wrote racist screeds and was escorted from historically Black institution Edward Waters University just before the massacre at the discount store.

As Jacksonville, and Florida more broadly, reels from Saturday’s violence, teachers worry that they can’t discuss the alleged hate crime for fear of violating state law. That — education leaders, politicians and activists say — is precisely the problem.

Florida has banned the College Board’s AP African American Studies curriculum and implemented social studies standards suggesting that enslaved people benefited from bondage. The state has also passed legislation that targets so-called wokeness in education; limits what can be taught about gender, race and sexuality; and facilitates censorship in school libraries.

-

Read Next:

“You can’t go around promoting hatred and disrespect of communities of color and then say, ‘Well, I’m sorry that you’re a victim of violence,’” said LeRoy Pernell, a professor of law at Florida A&M University. “That’s like lighting a stick of dynamite and then coming back and commiserating with the victims. So that type of approach needs to change.”

In the wake of the Jacksonville shooting, officials including state Rep. Angie Nixon, a Democrat representing the area, are accusing DeSantis of having “blood on his hands.” The governor has condemned the violence in the city off Florida’s northeast coast, but he was booed during a vigil following the rampage.

(Sean Rayford/Getty Images)

Representatives for DeSantis did not respond to The 19th’s request for comment before publication about whether the wave of controversial laws he’s overseen has fostered extremism in the state. Such policies contributed to the NAACP’s decision in May to issue a travel advisory for Florida, a move DeSantis criticized at that time.

“Florida is openly hostile toward African Americans, people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals,” the advisory states. “Before traveling to Florida, please understand that the state of Florida devalues and marginalizes the contributions of, and the challenges faced by African Americans and other communities of color.”

Andrew Spar, president of the Florida Education Association (FEA), the state’s teachers union, said that Florida’s laws have left teachers unsure as to whether they can discuss events such as the Jacksonville shooting because they are supposed to refrain from engaging in “woke” speech.

“It’s unclear right now whether or not teachers, especially high school teachers, which is where this would probably more likely be a topic, could have a discussion about race relations in today’s society and how it may have played a role, or did play a role, in the shooting in Jacksonville,” Spar said.

Prohibiting discussions about Black Lives Matter and the LGBTQ+ community in schools not only prevents students from feeling represented in the curriculum, but it also prevents teachers from making learning relevant, Spar said. Educators are frustrated that they can’t make teaching meaningful to their students’ lives, a dilemma that has contributed to the Sunshine State’s teacher shortage of roughly 7,000 professionals, up from about 6,000 last school year, the FEA estimates.

“As a parent, as an educator, I’m very concerned about what’s happening in public education in the state of Florida,” Spar said. “A safe, secure and high-quality education — that’s what the constitution of the state of Florida guarantees. And I do not believe the state of Florida is fulfilling that requirement.”

That’s because Black, Hispanic and LGBTQ+ students are not receiving the socioemotional support they need in school, Spar said, adding that the removal of library books representative of youth from these communities exacerbates the alienation they feel.

“What is a student to think when they see books about them being pulled off the shelves?” Spar asked. “What are they to think when they ask a question and are told by a teacher, ‘We can’t discuss that,’ but it’s relevant to them and their learning? So, we have a concern about the impact that these laws are having on kids — on both their academic success and their mental health.”

In March, the NAACP handed out 10,000 books to 25 Black communities in Florida in partnership with the American Federation of Teachers’ Reading Opens the World program. Most of the books are banned in schools due to the state’s various education gag orders, and the civil rights group encourages the opening of community libraries to improve marginalized youth’s access to literature that reflects them.

The NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund is also representing plaintiffs in a lawsuit against Florida’s Stop W.O.K.E. Act, which limits discussions about race and gender in K-12 and higher education classrooms as well as workplaces. Preliminary injunctions prevent the legislation’s enforcement in higher education and workplaces, but appeals are pending.

Pernell is one of the higher education plaintiffs, and he said last summer that he joined the lawsuit because he feared the legislation attempts to “erase the history and life experiences of Black people, LGBTQ folks, women and other people of color who struggle on a daily basis to achieve racial justice and make a positive change.”

He told The 19th that the Jacksonville gunman’s presence at an HBCU just before the shooting rampage is significant, for it is part of a pattern of the “educational silencing of the Black community.”

The professor is both concerned about censorship in classrooms and the distortion of history, such as the suggestion that enslavement may not have been “so bad” for Black people because they learned skills, he said. Denying students the chance to have access to a sophisticated and multifaceted curriculum, he added, allows racism to thrive.

“Education is the answer to racial ignorance,” Pernell said. “When you deny educational opportunities, you deny the chance for people to learn and to grow and to not react based just on ignorant fear.”

The Jacksonville shooting happened the same weekend as the 63rd anniversary of Ax Handle Saturday in which a White mob with baseball bats and ax handles attacked the city’s Black community. The 60th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, also took place close to the day of the shooting, but it’s unclear if Florida students know much about either of these events, given the state’s education restrictions.

(Saul Martinez/

Pernell would like Florida to respect the histories of diverse communities and the efforts to inform young people about them. He also wants political leaders in the state to take responsibility for using divisive rhetoric and introducing divisive legislation.

Florida state Sen. Shevrin Jones, a Democrat, said that through their words and actions, DeSantis and other Republican lawmakers “created the perfect formula” for the bloodshed in Jacksonville. He called it hypocritical for these politicians to condemn racism after enacting policies embedded in it.

He added that the NAACP hit the mark with its travel advisory for Florida, as did the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity when it decided in July to move its 2025 convention out of the state to protest its policies targeting communities of color and other marginalized groups. For similar reasons, the National Society of Black Engineers also decided to pull its upcoming convention out of Florida.

“I agree with them because it’s not safe for Black people,” Jones said. “If the governor was serious about being present for Black people, he wouldn’t have vetoed Democratic Black members’ appropriation that could have combated structural racism, institutional racism, and so on and so forth. The governor has to understand that the blood is on his hands.”

Year after year, violence against Black Americans constitutes the largest share of hate crimes, making up 31 percent of single-bias incidents in 2021, the most recent year of statistics available, according to the Department of Justice. The Jacksonville shooting follows last year’s slaughter of 10 Black people by a racist gunman at a grocery store in Buffalo, New York, and the 2015 killings of nine Black individuals by a white supremacist at Mother Emanuel Church in Charleston, South Carolina. In both of these racially motivated shootings, most of the casualties were women.

DeSantis’ stances on AP African American Studies and the Stop W.O.K.E. Act revealed who he truly is, Jones said, paraphrasing Maya Angelou’s famous quote: “When people show you who they are, believe them the first time.”

-

Read Next:

In the shooting’s aftermath, Jones would like to see hate crime laws with stiffer penalties passed, and he plans to file legislation to that effect in the state Senate. Florida also needs stricter gun laws, he said, arguing that policies such as permitless carry make residents less safe.

For these changes to happen, they will need support across partisan lines, but Jones and other DeSantis critics doubt the governor will invest in the Black community as he should. DeSantis plans to allocate $1 million to help Edward Waters University beef up security since the gunman showed up at the institution and HBCUs nationally have been targets of white supremacist threats. The families of the shooting victims will receive $100,000.

Still, Jones is skeptical about whether DeSantis will prioritize Black Floridians after Jacksonville because the governor did not fulfill his promises to Orlando’s LGBTQ+ community after an anti-gay gunman killed 49 people and injured 53 others at Pulse nightclub in 2016. Instead, DeSantis has gone on to pass a series of anti-gay policies.

Brandon Wolf, an LGBTQ+ advocate and survivor of the Pulse shooting, expressed similar concerns in a statement to The 19th in which he decried how the nation’s gun violence epidemic continues to needlessly tear families apart.

“Those like Governor DeSantis, who use hate and bigotry as fuel for their career ambitions, are making things worse,” Wolf said. “This governor’s agenda of fomenting racist hate, emboldening anti-LGBTQ extremism, and peeling back common sense gun safety guardrails makes Florida more dangerous for all of us. It does not have to be this way, but solutions to this crisis will only come about with a change in our politics.”

Carlos Guillermo Smith, a senior policy advisor with Equality Florida, which advocates for the rights of LGBTQ+ residents, is not counting on DeSantis to implement radical changes in the state because he said the governor has a history of pandering to extremists, including failing to denounce neo-Nazi supporters. The governor’s treatment of Pulse nightclub survivors also makes it difficult for Smith to believe that he will give Jacksonville’s Black community the support it needs.

“On June 12, 2019, Ron DeSantis visited Pulse nightclub, and he promised to always remember these precious lives,” Smith said. “Then on June 2, 2021, just a couple of years later, Ron DeSantis vetoed funding for Pulse nightclub survivors and families. So when I see him showing up and making promises of solidarity with marginalized communities who have been targeted and have been gripped by gun violence, I don’t believe him.”

(Sean Rayford/Getty Images)

Smith, however, would like to see his state enact policy change, including the strengthening of gun safety laws, the teaching of “honest history” and the celebration of diversity, equity and inclusion. Florida hate crimes laws also need to be updated, he said, because they don’t require bias crimes to be reported to the federal database, which means that many of the state’s law enforcement agencies simply do not collect hate crime data.

“It is impossible to solve a problem when you don’t have information about the problem in the first place,” Smith said.

Pernell believes that education is the key to preventing future hate crimes from occurring because it helps students unpack racist ideologies. He stressed, though, that Florida lawmakers have enacted education policy with the perspective that the United States is now post-racial, an idea he disputes.

“We have to recognize that the threat is still there,” he said. “What we saw in Jacksonville shows us it’s not in the past. It’s right now, and we have to recognize that the danger is a real and present danger and that we have to stop fueling it.”