Interview with Ming Wong on the occasion of his solo exhibition “Cosmic Theatre” at Ota Fine Arts (Roppongi). The exhibition runs until October 21, 2023. (Edited by Alena Heiß)

Berlin-based Singaporean artist Ming Wong (1971-) is currently holding his solo exhibition Cosmic Theatre at Ota Fine Arts in Roppongi from September 2 to October 21, 2023. Wong creates works that reenact film and popular culture through various mediums, including performance, video, installation, and photography. His unique pieces explore people’s identities, social structures, and cinematic language. In recent years, he has also deepened his exploration of traditional Cantonese opera. The Wayang Spaceship in Cosmic Theatre is a collage of Cantonese opera films, science fiction films from the former Soviet Union, and footage of himself playing an astronaut.

On the occasion of the solo exhibition, Tokyo Art Beat sat down with Ming Wong and Kyongfa Che, curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, to explore the history of Cantonese opera and film in Singapore, as well as works that question nationalism, the ways of transnationalism, and cross-gender representations.【Tokyo Art Beat】

——You have a long-standing interest in Cantonese opera, but what was the first thing that drew you to it? Is it related to the fact that you studied Chinese painting at the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) or that opera was also your family’s practice?

My aunt by marriage, Joanna Wong, is an opera actress and a living treasure for Cantonese opera in Singapore. She was a cultural ambassador for the country after independence and joined many missions as a Chinese performing artist. She was born in Penang when Malaysia and Singapore were still collectively known as British Malaya, and later studied at the University of Singapore, where she met my uncle, who wrote operas for her to perform.

——Were the operas reflecting on her migration to Singapore or based on more traditional narratives?

I didn’t know that until later, but my uncle wrote original scripts based on Chinese history and mythology. I myself used to be a playwright. In my early days at NAFA, I did Chinese painting, calligraphy, seal carving, art history, and literature. But outside of that, I was writing plays for the English-language theater scene in Singapore.

——What kind of plays did you write?

I won a student play-writing competition and had my first professionally produced play, Wayang Sayang. In short, it was about the meeting between a Wayang (Chinese street opera) actress and a young man who happened to go backstage.

——Is it autobiographical, too?

Yes, at that time, I often visited the backstages of Wayang, taking photographs for making prints and paintings. Some of those early works are now in the Singapore Art Museum collection. But because I observed life backstage, I found it even more interesting than “onstage” life. On stage, you could see people who play emperors and empresses, princes and princesses, mythological gods and goddesses, and historical heroes – but backstage, it was chaos; they were shouting, sweating, rushing about, and cursing. However, they would be transformed once they crossed the ‘line’ to enter the stage. I found backstage life fascinating, and it inspired me to write Wayang Sayang, which has been presented several times.

——You also wrote plays where the cast included people from different ethnic backgrounds, right?

Yes, even though I was part of the English language theater scene in Singapore, I was writing scripts in different languages and different kinds of ‘English’ – because, in Singapore, no one speaks “pure” English. There are people with different education levels, and most communicate in ‘Singlish’ (Singapore English) and mix different languages and slang words. This is where I got my love for languages and learned that you can be creative with them. At the time, radio and television tried to be more correct with the languages spoken, but in the theater, it was free, and I played with that. Theater is not just spoken language; there is a lot of nonverbal communication and expressive physical performance. “How” you say things means more than “what” you say. I suppose that is how performance and language became foundational elements in my practice.

——This is reflected in the many works that you created afterward. For example, you often reenact several characters in the same film.

Yes, I usually play characters that I could not play normally. But intentional wrongness became part of the practice – the strategy was to use wrongness as a way out of being limited or controlled. I observed my friends from the Singapore theater scene, who were excellent actors, would always get the same stereotypical roles, such as prostitute, cook, refugee, or gangster when they went for casting in America or England at the time. I felt their frustration, so I made it a part of my strategy to play every role – young or old, male or female from a different class, race, or nationality, and speaking a different language, every role as different as possible from my own identity. Miscasting became a device to produce an alienation effect. You would then focus on the role being presented and try to understand what the director or writer is trying to do with it.

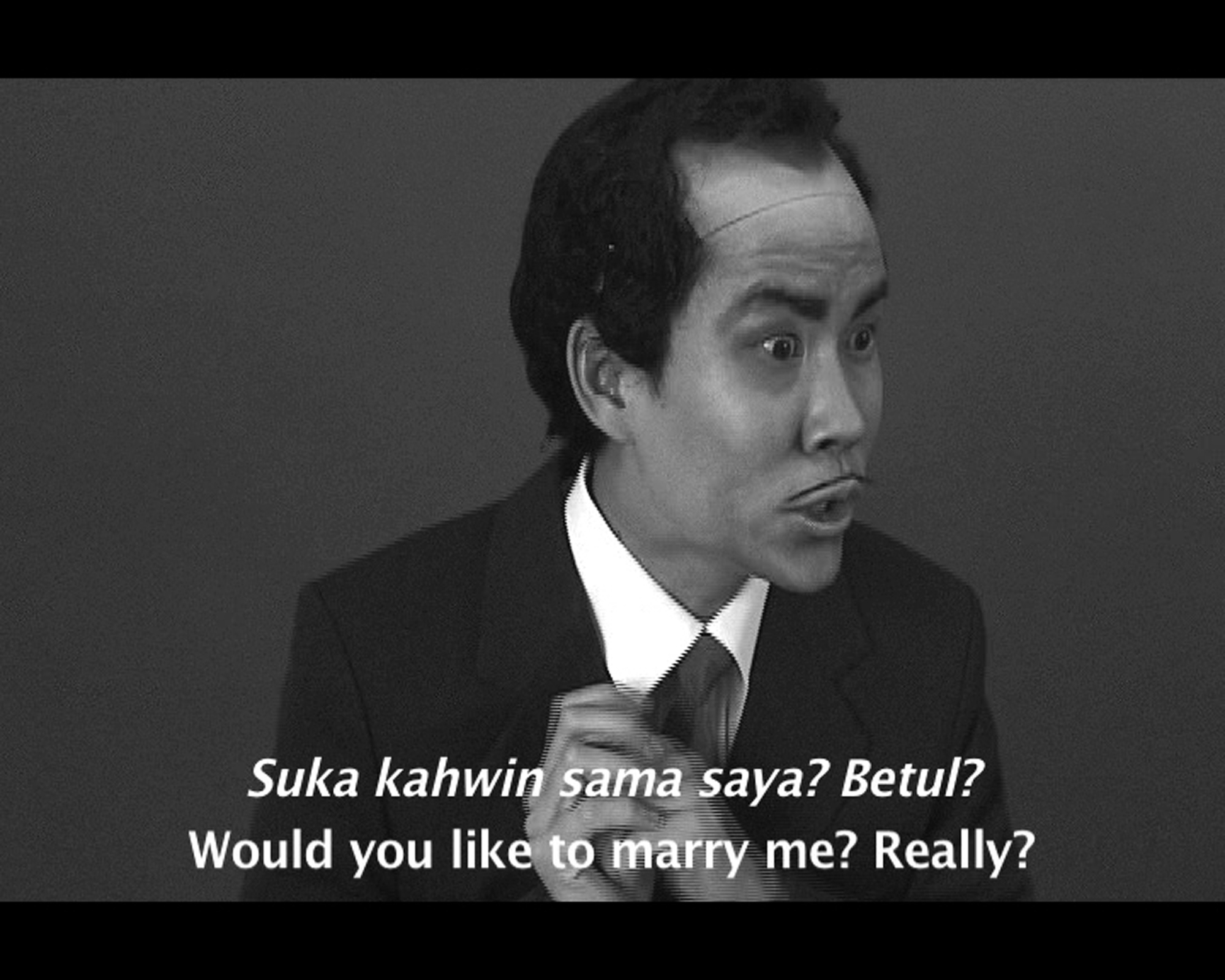

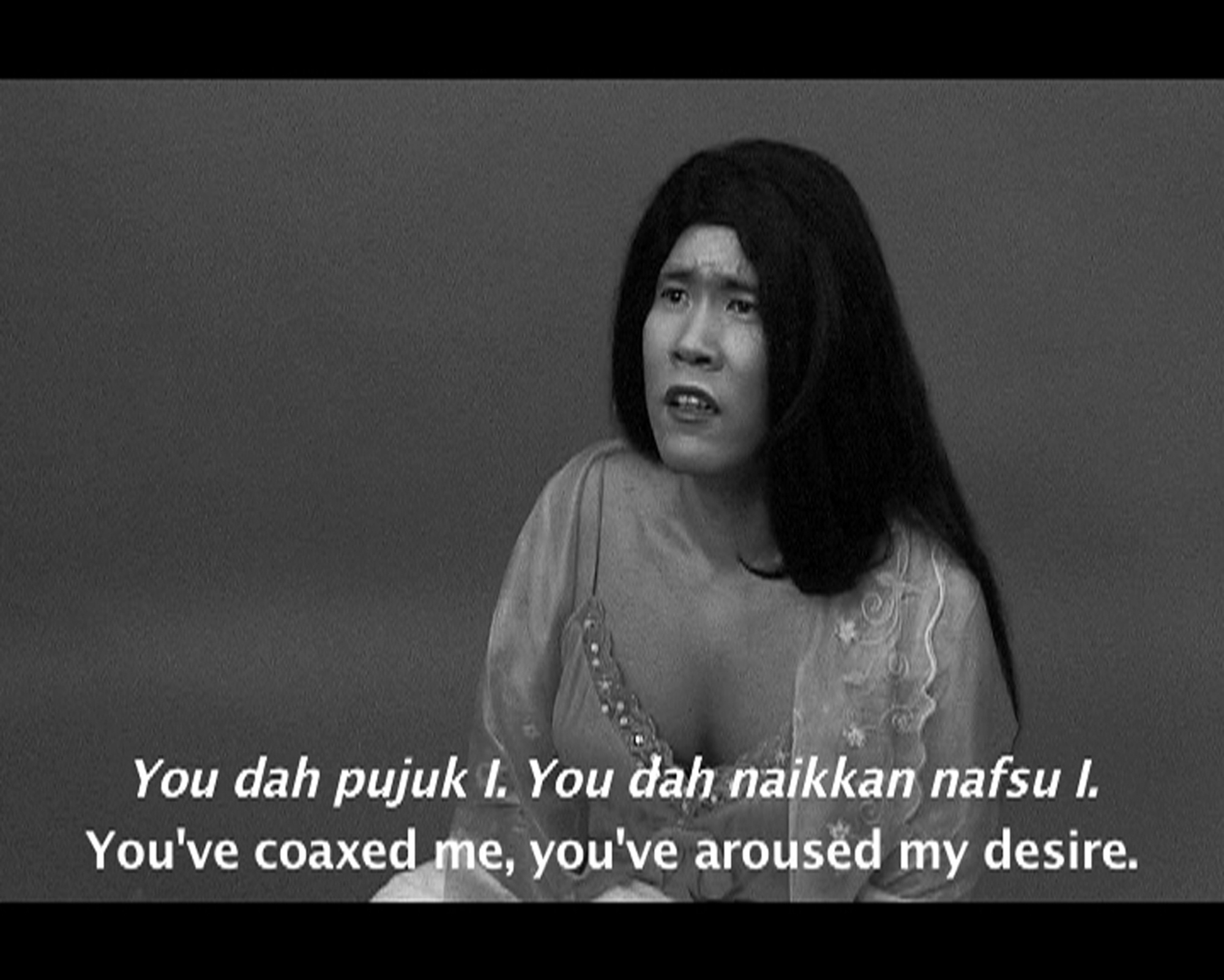

I first discovered it when I returned to Singapore after several years in London. I was inspired to work with the Malay movie industry in Singapore, which had its golden age in the late 50s and early 60s but was in danger of becoming a forgotten part of the complex social history and politics of the time. The money came from Chinese producers who owned the cinemas, and they hired Indian camera operators and directors from Bollywood, the closest mature film industry in the region. The stars were Malay actors, singers, and dancers from Malaysia and Indonesia.

I reenacted several of these movies and played all the characters, although they were Muslim Malay characters from the 50s-60s. What was deemed modern at the time has become conflicted in contemporary society – for example, I chose to re-enact scenes with women talking openly about their sexual desire or with characters cursing and invoking religion, etc. My Malay Muslim friends said they couldn’t play those roles for fear of antagonizing their community, but because I was Chinese Singaporean, it was easier for me to enter those roles with a distancing effect.

——Do you think narratives during that time could function as a critique towards the mythology of Singapore as a nation of multiculturalism that came after?

Indirectly, yes. I’m very interested in notions of nationalism and national cinema, and I questioned it when I made the Singapore Pavilion for the 53rd Venice Biennale (2009). This project’s stories are the basis for the larger exploration of what ‘national identity’ means, especially in an international platform like the Venice Biennale, which is structured on the idea of national pavilions.

The new nation of Singapore wants to present a multiracial but majority Chinese façade and not overstate its past links with Malay culture. The other issue is to distinguish Singapore’s diasporic Chinese identity as distinct from mainland Chinese identity. For example, in acknowledging Singapore’s Chinese roots, the government has opened the Singapore Chinese Art Centre, which focuses on reclaiming the diversity of Southern Chinese dialect groups (Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, etc.), which had been suppressed in earlier decades.

——I missed your presentation at the Venice Biennale, but you mentioned somewhere that it was not only the critique, but there was also a sense of celebration. Can you explain what it was and how it was rendered?

The exhibition celebrated Singapore as a cultural melting pot long before other countries were trying to deal with multiculturalism. I chose to express it through the little-known but unique cinema heritage of Singapore. I showed reenactments of several films that played with ideas of nationality, race, gender, and language. For example, in the remake of the Hollywood movie Imitation of Life (1959) by Douglas Sirk, I had Singaporean Chinese, Indian, and Malay male actors take turns to play Black, White, and mixed-raced American female roles. And in the remake of Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000), a Caucasian actress attempts to deliver her lines in Cantonese, which she doesn’t know. There were three video installations, but we also had a lot of archival materials that we borrowed from a Singapore collector of cinema ephemera. The pavilion was indeed a national pavilion – it was about Singapore as a source of inspiration for generations of artists working in moving image and performance.

——After the Venice Biennale, you returned to your interest in Cantonese opera coming from a young age. How did it unfold this time in your practice?

Since 2010, I have visited Hong Kong yearly to conduct research on its cinema history, and the beginning of it comes from Cantonese opera cinema. Since the late 19th century, Cantonese opera troupes would travel from Hong Kong harbor to America and Southeast Asia to perform for the diasporic Chinese communities. In America, they encountered Hollywood cinema and brought the stories, music, and technologies back to China via Hong Kong, where they adapted Cantonese opera for the silver screen. The 50s and 60s were the golden age of Cantonese opera cinema – many movies reflected the modernity of the times and the hybridity of city life in Hong Kong, featuring contemporary settings, costumes, and songs about contemporary life.

——In this sense, does modernity equal Westernization?

In that historical sense, yes. But as I kept returning to Hong Kong over the past decade, I also observed the many changes happening in the city: for example, when Art Basel arrived, and many blue-chip art galleries opened, as a sign of the capital flowing out of mainland China. But at the same time, there was social unease with the mainland Chinese government, and numerous protests started to break out. The question on everyone’s minds was: what was the future of Hong Kong and China? I decided to look at it through the lens of science fiction. What was science fiction in mainland China? I studied the history of science fiction in the Chinese-speaking world and learned that it had risen and fallen over the 20th century, and we are now in the third wave of it. I tried to connect the two strands of my artistic research, and along the way, I have done several projects that fused my interests in the parallel histories of Cantonese opera cinema and science fiction in China.

I also studied the architecture and the history of the traditional Cantonese opera bamboo stages in Hong Kong. The traditional bamboo theaters form part of the country’s unique cultural heritage, which continues to flourish in spite of the death of the craft in mainland China after the Cultural Revolution.

When the Singapore Art Museum asked me to propose a public art project about two years ago, I decided to create the Wayang Spaceship. Since the time I took the photographs of Wayang backstages in the late 90s, the local Chinese opera stages have practically disappeared. I found one last Chinese opera stage builder who had inherited the materials and knowledge from his father, and with his help, the “Wayang Spaceship” was built.

The foundation was made from rare Southeast Asian maritime timber. The decorated panels and external canvas shell were redesigned by me and refashioned with mirror-reflective surfaces used in agriculture and space programs. Furthermore, in experimenting with mirrors, fluorescent tubes, and layers of dichroic film, I managed to develop an abstract scenography with color combinations found similarly in costumes from Cantonese opera. The way salmon pink is matched with mint green or how yellow is contrasted with blue and purple – these combinations emerged in my experiments in manipulating the visible spectrum of light.

However, the most exciting part is when the whole “Wayang Spaceship” lights up at night, and the one-way mirrors and layers of dichroic films provide the holographic effects of infinity. By day, the stage reflects its surroundings and is ‘camouflaged,’ but when night falls, it transforms into a kind of portal for the transmission of a science fiction Cantonese opera. The nightly activation in front of the container port terminal at the back of the Singapore Art Museum harks back to the time when Wayang stages arrived with the opera troupes by boat. The Spaceship comes alive only after the museum closes at seven, which was a deliberate decision to acknowledge the transition of day to night, which was when families used to go to see the Wayang.

——This exhibition includes the video originally presented in Wayang Spaceship. It is a collage of footage of your alter-ego “scholar warrior” wandering in the spaceship and several archival footage of Cantonese opera and sci-fi films. Can you elaborate on your intention behind combining these materials?

The footage is a collage of Cantonese opera movies and science fiction films from the same era. These science fiction films are mostly from the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, from the late 50s and early 60s, which was when the best writers, artists, musicians, designers, etc., turned to science fiction to express their utopian ideals. I included Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, but Kubrick also took inspiration from these movies from the Soviet Union.

The Cantonese opera film clips all feature the actress Yam Kim Fai, one of the most famous male impersonators in Cantonese opera. You can see her playing female and male roles, contemporary and historical, as well as mythological characters. You see this same protagonist traveling through space and time and gender, and occasionally, there are astronauts in the background, which could be strange at first, but I think it is not so implausible. I found interviews with Chinese astronauts in which they referred to Chinese mythology in their dreams and reflections. For example, the first Chinese female astronaut, Liu Yang, dreamt of Sun Wukong, the Monkey King, walking in the clouds when she was in space. Many spaceship names are derived from China’s myths and legends, too. It’s strange but humbling to realize that my current research has brought me back full circle to when I started with Wayang Sayang as a young playwright and artist.

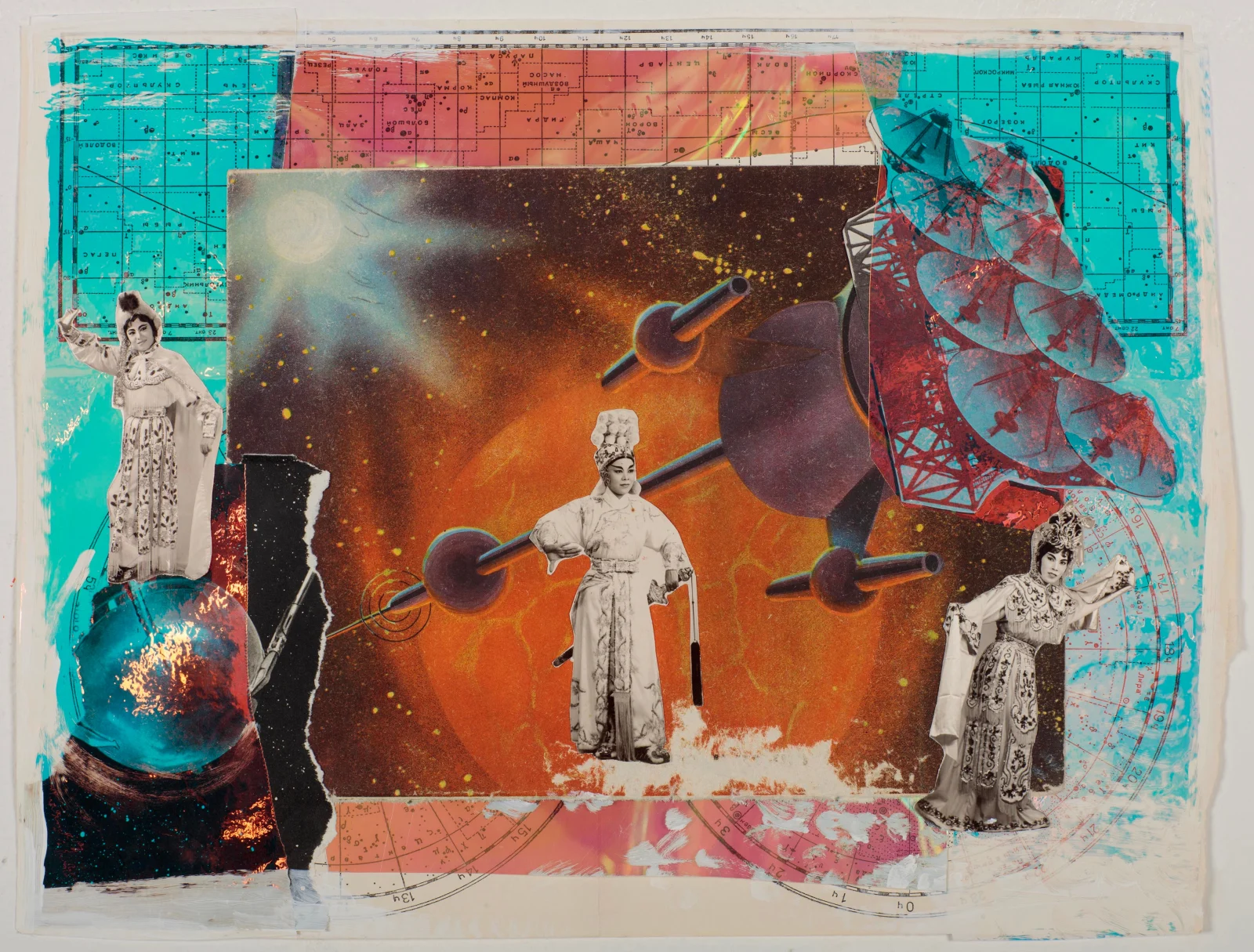

——The exhibition also features a series of photo collages. What is the process behind making them?

The photo collages feature mostly female Wayang opera actors from Singapore and Malaysia from the 50s-60s who perform male roles. They are taken from promotional studio photographs. Then, I created scenographies for them from illustrations from Soviet science fiction magazines and books from the same era. I also experimented with layers of dichroic film and flash photography to get the fiery, ‘other-worldly’ colored light effects that remind me of Kubrick’s “2001,” when the character goes into the fourth dimension. To complete the picture, I did some brushwork on paper to combine the different elements. As I mentioned earlier, everything connects in a circular way, so I came back to a kind of Chinese landscape painting, too, melding multiple temporalities.

——The works in this exhibition explore the transformation of Chinese culture brought about by migration or adaptation of other cultural forms. Meanwhile, you have produced other works in recent years that observe the political and ideological dynamics China creates in other regions or nation-states in the present and the past. In Hand in Hand (2019), for example, the camera follows you walking around the city of Dakar and visiting monumental infrastructures that China sponsored. There, you obscure your identity and show how your Chineseness plays out in a place where China is obtaining large economic and ideological influence. In both streams of work, there seems to be your ongoing query of what it means to be Chinese.

My work is rooted in a search for identity and how it is formed. As a third-generation Chinese Singaporean artist living in Europe for the past 30 years, I reflect on what it means to be a creative person of Chinese descent and my position in the world. “Chinese” means many different things, and it is important to keep pointing out the complexity of its meanings. It affects how I am seen and presented and how I function as an artist in this world. There was a time when people were interested in Chinese art and invited artists from mainland China, Hong Kong, or Taiwan but not Singapore – I was considered not ‘Chinese’ enough to be part of that group. Now, I am often considered to be part of the Southeast Asia art scene, even though I do not live there anymore. People create these boxes to categorize you.

Then, when the pandemic started, it didn’t matter what kind of Asian you were; you would be subjected to anti-Asian racism and be blamed for the so-called ‘Chinese virus.’ This issue doesn’t stop there. For my latest project, I’ve been looking into the diplomatic relationship between America and China for the last 50 years, since Nixon shook hands with Mao in 1972 – it has been only 50 years since America normalized ties with mainland China. From an era of optimism and engagement, we have arrived at a somewhat treacherous timezone of mistrust, decoupling, and hostility. My recent lecture performance, Rhapsody in Yellow (2022), focuses on the choices – will you play on America’s side or go with China? – and the tensions that come from having to make those choices. Singapore has been doing it for the longest time, and the tightrope is getting shakier. As an artist, I try to be a bridge between worlds. I am from neither side, but I can code-switch between them. I can play the outsider-insider.

——Thank you for your time.

Ming Wong answers the question, “What is art?” on Tokyo Art Beat’s official YouTube channel:

Learn more about the exhibition at Ota Fine Arts: