This is the first in a multi-part series of conversations with residents of this southwestern Minnesota community. Seeds of Justice organized the event on behalf of Minnesota Women’s Press. Interpreters, child care, and transportation services were made available from our member supported Changemakers Alliance funds. Local residents moderated the event and represented multiple generations. Locally catered Latine and Ethiopian food was paid for by the Wilson Fund of First Unitarian Society of Minneapolis.

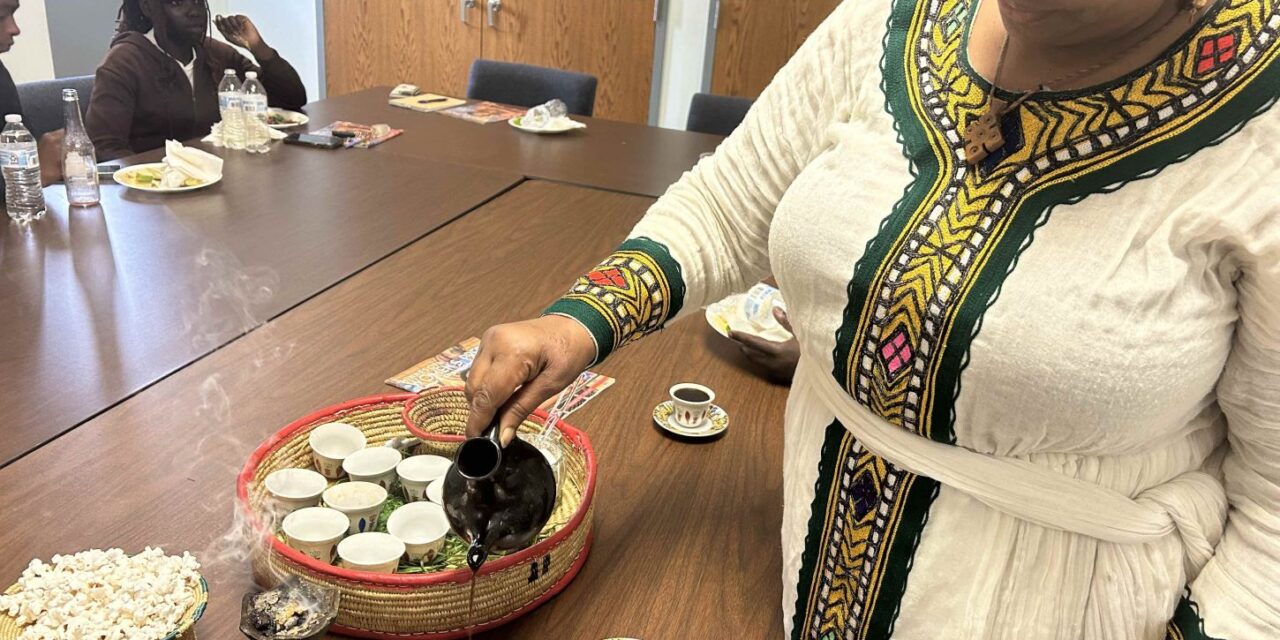

An Ethiopian coffee ceremony was prepared alongside traditional Eritrean food

Worthington — population 13,000 — has been the location of two national stories in recent years, both related to the JBS pork-packing factory that employs many members of its immigrant families.

In April 2020, during the start of the pandemic, the factory continued operating in tight working quarters and many employees died of Covid-19. State health officials tested at the plant in April 2020 and found that nearly 550 workers at the 2,000-worker plant had Covid, according to a Minnesota Reformer story.

The JBS plant was also named in a U.S. Department of Labor investigation as one of the sites where a cleaning service for meatpacking plants used child labor, starting at age 13, often in overnight shifts to clean saws and other dangerous equipment, with exposure to ammonia, feces, and blood. The U.S. Department of Labor fined Packers Sanitation Services $1.5 million in penalties for its practices at 13 plants in eight states. Federal law prohibits children younger than 16 from working for more than three hours or after 7pm on school days.

An extensive investigative story about migrant child workers, by Hannah Dreier of The New York Times in February 2023, reported: “In Worthington, Minn., it had long been an open secret that migrant children were cleaning a slaughterhouse run by JBS, the world’s largest meat processor. The town has received more unaccompanied migrant children per capita than almost anywhere in the country. Outside the JBS pork plant last fall, The Times spoke with baby-faced workers who chased and teased one another as they came off their shifts in the morning. Some said they had suffered chemical burns from the corrosive cleaners they used.”

Labor inspectors found 22 Spanish-speaking children working at the plant. The Labor fine led to an end of the child cleaning labor, but The Times reported that many of the children found work in nearby plants. A 17-year-old was quoted saying, “I still have to pay back my debt, so I still have to work.”

The young children said they are paying debt to smugglers who helped them immigrate into the country, unaccompanied by caregivers. According to The Times, this new “economy of exploitation in the U.S.” happens in every state, leading to deaths of children who worked as roofers, slaughterhouse workers, and at wood-sawing plants, among others. The Times article indicated, “This labor force has been slowly growing for almost a decade, but it has exploded since 2021, while the systems meant to protect children have broken down.”

Worthington Voices

Worthington Voices

Minnesota Women’s Press visited Worthington and talked with 30 residents about their experiences in the city. Most participants who came to the discussion were from immigrant communities — including Mexico, Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, and Laos (see sample languages from the survey we took prior to the event).

Lack of local opportunities — and optimism that change can happen — for non-white residents emerged as a theme during our three-hour conversation in Worthington.

Several high school students attended the conversation, and indicated they feel youth of color are treated differently, despite being a large percentage of the student body. For example, a high school student indicated that when he and others organized a student rally about Black Lives Matter after George Floyd was murdered, school administrators gave them 15 minutes for the protest, indicating they would be marked absent from class. Yet when a student protest was organized against wearing masks during the pandemic, there was no time limit for students.

A long-time member of the community who is Latine said that when she sat down next to a white woman at a cultural diversity meeting, the woman said: “You’re not going to steal my purse, are you?”

One of the women at the conversation, who attended with her young children, indicated that her husband was one of the JBS factory workers who died during the pandemic.

Andrea Duarte-Alonso, a Worthington native who has written columns for Minnesota Women’s Press, recorded a series of interviews with Worthington residents called “Stories From Unheard Voices.” She is a Rural Regenerator Fellow with Springboard for the Arts, and works as a communication arts teacher in Worthington.

One of her Unheard Voices interviewees concluded by saying: “It would be nice if people were more culturally aware and accepting. For example, someone who is a non-English speaker might have a tougher time communicating because of language barriers but that doesn’t make them less than a human. Just because they have a language barrier, it doesn’t mean that they’re dumb. Worthington will always be home, but I am genuinely disappointed that my friends from school know my hometown as the town that ‘has bus drivers that are unkind to children because of the color of their skin.’”

In 2021, after President Biden was elected, Duarte-Alonso shared a commentary at womenspress.com: “During the inauguration, I looked over to my mother with admiration for her resiliency and her hope (even if dimmed). Like many other immigrants, she wants to focus on the present with her family and see her life advance and change for the better. My hope is that noncitizen immigrants won’t feel remorse for deciding to migrate to a country of ‘prosperity’ and ‘freedom,’ but can demand a better system of immigration rights than the one that has been built on white supremacy.”

Cheniqua Johnson, who graduated from Worthington High School with Duarte-Alonso, unsuccessfully ran for state representative in the community in 2018. Today she is running for city council from her home in Saint Paul. After graduating from the University of Minnesota, she worked with then-Congressman Keith Ellison and Hennepin County Commissioner Angela Conley. She works on health, civic engagement, and domestic violence portfolios for the Saint Paul & Minnesota Foundation and served on the 2022 police chief selection team for Saint Paul.

She told MPR’s Angela Davis in 2021: “I thought it was really important to have people know that a Black woman who was 22, 23 at the time of the campaign could run for state rep. …. It forced a larger conversation. Which I think was ultimately the goal of running, was to force conversations here locally about challenging what we see when we see an elected official.”

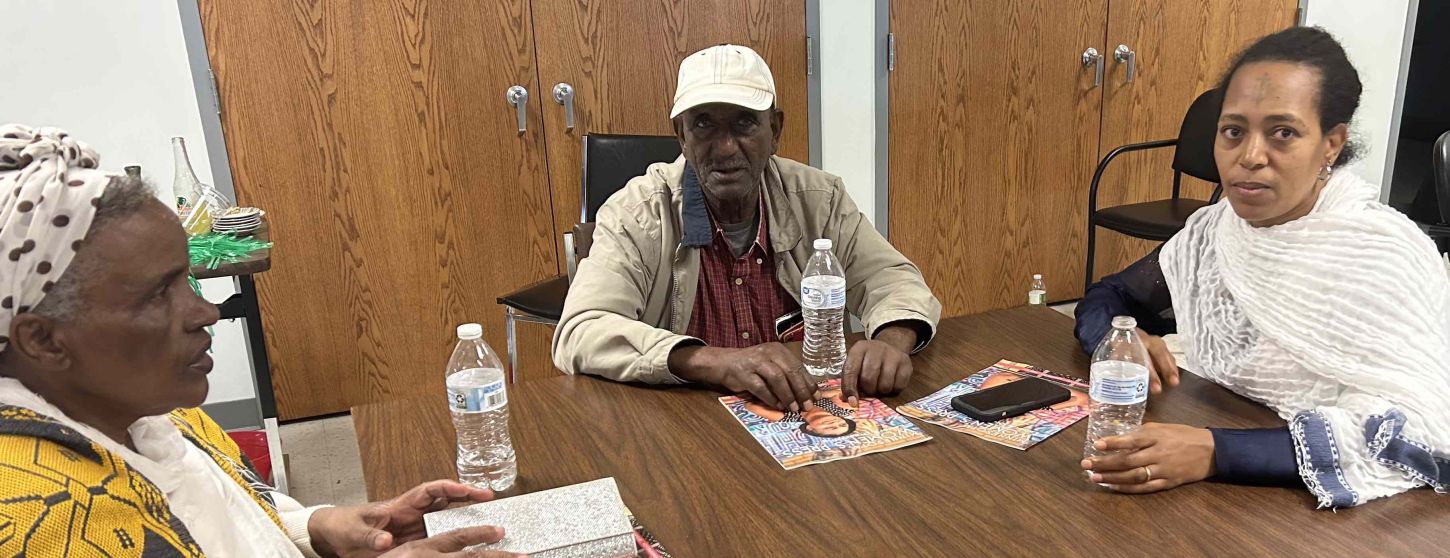

A few attendees at the Worthington conversation for the “Hometown Values & Vision” series

Seeking Diversity in Community Leadership

A majority of Worthington High School’s 800-plus students are non-white, which reflects the diversity of the community. Yet all members of the school board and city council are white.

Elaine said her father was the first Black man in the community. He worked at Campbell Soup and found migrant workers from Kansas City and Oklahoma for the temporary work at the factory. She spoke earnestly and at length about both her love and frustrations in the community. She says she has a college degree and has worked with children who have autism and other special needs but is unable to get paid work in the school district. She says she has the patience to work with kids: “Quit putting kids on medication. Give them to me. They need to be challenged.”

One of her daughters is thriving at Hamline University. “She’s doing amazing things. She says, ‘Mom, I’m not going to come back there. Why are you still there?’ And I say, ‘This is my community. They need hope.’” Elaine said she recognizes why her kids have to take opportunities elsewhere, because there are not enough opportunities for young people of color in Worthington.

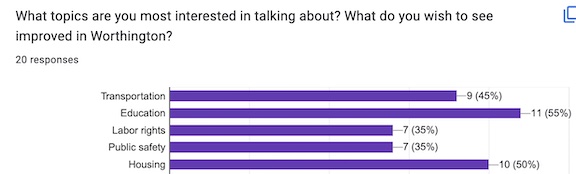

We asked participants in advance of the meeting what topics they were most interested in discussing

Despite the frustrations, Elaine says, “I raise money and give in the community. If they call me, nine times out of 10, I’m going to show up regardless of what it is. You bleed just like I do.”

She appreciated being able to talk with people from outside the area about the issues the community is facing. “It seems like all the information from the cities stops at Mankato. I don’t think [people] know we’re part of Minnesota. What is available to help people like me and other nationalities never makes it here.”

Seeking a Unifying Space

Elaine indicated that, as a lifelong resident, she speaks up loudly at meetings about inequities but is often the only one, and gets dismissed without support of others. “Sometimes I feel like I’m hustling backwards. I’ve fought the hard fight, and nothing came out of it,”she says. “When community doesn’t show up, that’s like putting a hole in my heart. I can keep moving and keep moving and keep moving. When you have people that know that what you’re fighting for, that is beneficial.”

To increase community engagement among residents who feel marginalized, the Seeds of Justice — a local organization focused on supporting the communities of color in Worthington — is seeking partnership and funding to create a community center. According to co-leaders Aida Simon and Leticia Rodriquez, who organized our conversation with locals in Worthington, Seeds of Justice addresses barriers to access, such as transportation, community projects, language barriers, and work so that all people of color feel welcomed and supported.

The group has organized food distribution events with Second Harvest Heartland, provided pandemic vaccines and free testing kits, worked on the legislation to support Drivers Licenses for All, offered healing circles and recovery work with local youth and families, and discussed economic crisis in focus groups with the Federal Reserve.

Rodriguez ran for Noble County commissioner in 2020; she was not elected. She would have been among five people that oversees the budget and the overall economic and civic vitality of the county — and the first woman of color elected to the role. Simon came to the area as a refugee from Eritrea and was seeking a seat on the Worthington City Council that same year; also unsuccessful.

In 2019, the Washington Post profiled the the fear, anger, and racism of the area by many older, white residents in the area in particular. Donald Trump easily won Nobles County in 2016. Past Minnesota Women’s Press writer Sarah Lahm wrote a story about the election campaigns of 2020 for “In These Times.”

Neighboring Assist

Minnesota Women’s Press invited Jessica Rohloff, of Willmar two hours north, to join us at the discussion; she was a featured story in our September magazine issue about organizing WHO. After listening to the conversation for several hours, she offered insights about how progress was made in Willmar, where there were similar obstacles for especially immigrant families.

“We’re still working on things, but we did have some big wins,” she said. “You are 100 percent right — when you’re the one person that comes in, the leaders of the meeting can chop you off at the neck. … We turned over at least half the city council because we could get no housing built in Willmar. We had too many developers on the board who didn’t approve construction unless they were building it. Now you will see how many new apartment complexes we have in Willmar.”

Rohloff added that the work can be scary. “We had undocumented people stand up, who had lived in the community for 20 years. … There was a lot of talk amongst ourselves about safety. If you start to be effective, that is when you’ll start getting the death threats, and all of the other things that come with it, so you have to know who has your back. When you’re leaving the meeting together, you text and call each other when you get home. You check in the next day, just to say, ‘hey, that was some heavy stuff. How are you feeling today?’ It takes that level [of commitment to each other].

She also indicated that voting power is important. “We had a collective group of people — those eligible to vote, and those who were not — vote together in a room and then pledge that those who had votes in the political system would agree to support the candidates that the group voted for. That is how we amassed voters and nonvoters together. Every city is different, but I just want to bring a little hope in the room.”

Minnesota Women’s Press plans to have additional stories from Worthington, and Willmar, thanks to our Changemakers Alliance fund. See our related essay by our Outreach Director Crystal Brown.