By Alexa Spencer | Word In Black

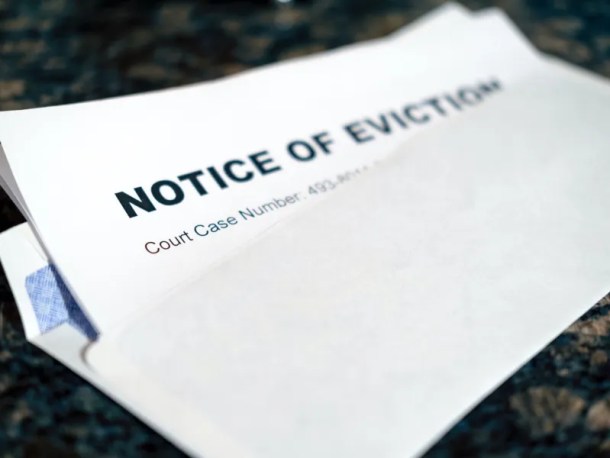

(WIB) – A slip taped to the front door. Sheriff deputies knocking, demanding to be let in. Beds, clothes, and family keepsakes piled up on the curb. One night at a shelter. Months at a cramped hotel.

Eviction is incredibly destabilizing.

Trauma rests in the family of anxiety.MICHAEL A. LINDSEY, DEAN OF NEW YORK UNIVERSITY’S SILVER SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK

For children, it’s an inescapable tossing and turning. It creates a feeling of mourning that can morph into years of mental and emotional suffering if untreated.

That’s why researchers like Bruce Ramphal, a Harvard University Medical School student, are digging deeper into its long-term effects on children.

A Bronx native, he grew up witnessing his neighbors being put out of their homes while his family lived on the edge of housing loss.

“There are so many elements of eviction, from the leading up to it, the possibility of court cases, the police contact, the frank dehumanization of Black people often [by] white people with power over your basic human rights,” Ramphal says. “All of that stuff is, I imagine, traumatic.”

Eviction Disrupts Child and Infant Health

Michael A. Lindsey, dean of New York University’s Silver School of Social Work, says trauma is the first thing that comes to mind when he thinks about eviction.

He says in children, who sometimes struggle to verbalize their mental illness, it could manifest in a number of ways.

“Trauma rests in the family of anxiety,” Lindsey says. “And so, think about all the physiological consequences of that experience. It will be trouble eating. Or maybe overeating to cope.”

The trauma may also show up as a “volatile” type of anger, depression, or shame.

“They’re going to experience the trauma and the effects of it based on having their peers or neighbors see that they’re evicted or the constant questions about ‘what’s going on with your family situation,’” Lindsey says.

Loss of housing is connected to preterm and low-weight births, and infant mortality.

Ramphal considers eviction as “disruptive to childhood development.”

“You’re not going to school right after you get evicted, probably,” he says. “You’re immediately homeless.”

Students who are unhoused are known to experience delays in developing literacy skills, display lower school achievement, and are more likely to be chronically absent or drop out of school.

Eviction also exacerbates poor birth outcomes for pregnant women and babies.

According to a recent study by Ramphal and a team of researchers, loss of housing is connected to preterm and low-weight births, and infant mortality.

Black Children Are Most Vulnerable

Systemic racism traps Black caregivers and their dependents in cycles of housing insecurity.

According to a 2020 study by the ACLU, Black women renters face eviction at double the rate of white renters. When they’re the sole caregivers of children, their kids become homeless, too.

Nearly 20% of children born to Black mothers experience eviction, compared to 11% of white children, according to a 2020 study by the Urban Institute.

Leah Goodridge, managing attorney for housing policy at Mobilization for Justice, says racist policies are pushing Black mothers and their children out.

“There have been a lot of cases in that regard of where someone is being evicted, and the legal reason is a nuisance, but it’s very racially coded,” she says.

Nearly 20% of children born to Black mothers experience eviction, compared to 11% of white children.

For example, an eviction might be filed for children running around the home — or even due to domestic violence.

“There are a lot of states that still have laws where if you are a DV victim and you call the police three times or more, they will actually force your landlord to evict you under the guise of nuisance,” Goodridge says.

She says the nuisance ordinances are disproportionately affecting Black women.

“These are instances where people are asking for help, and in response, they are punished.”