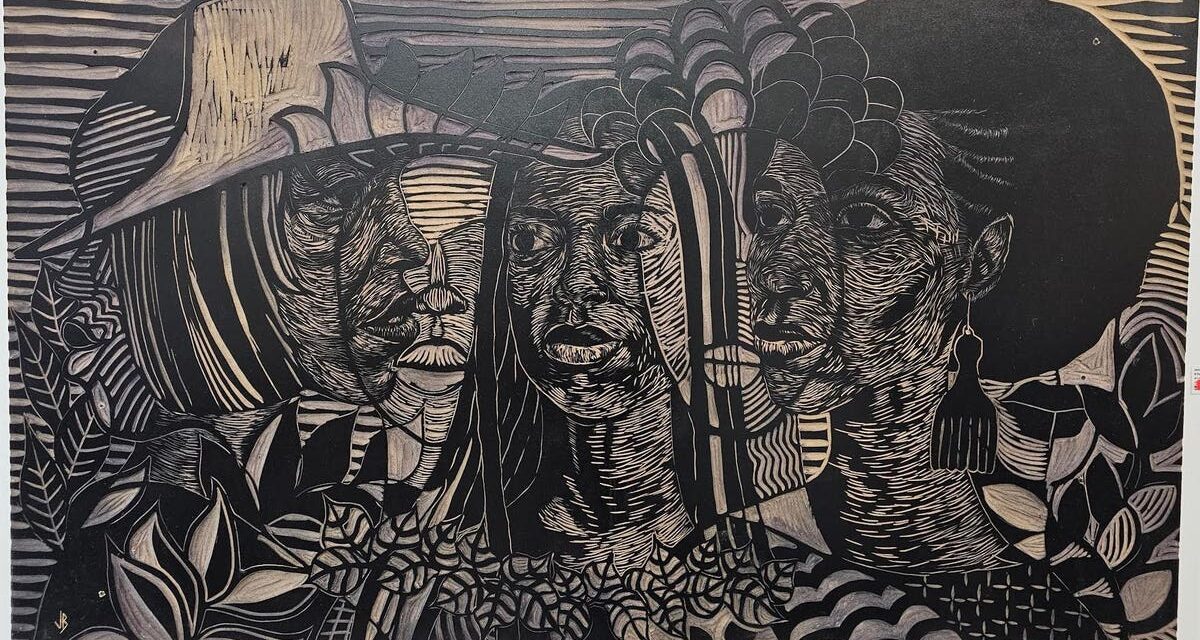

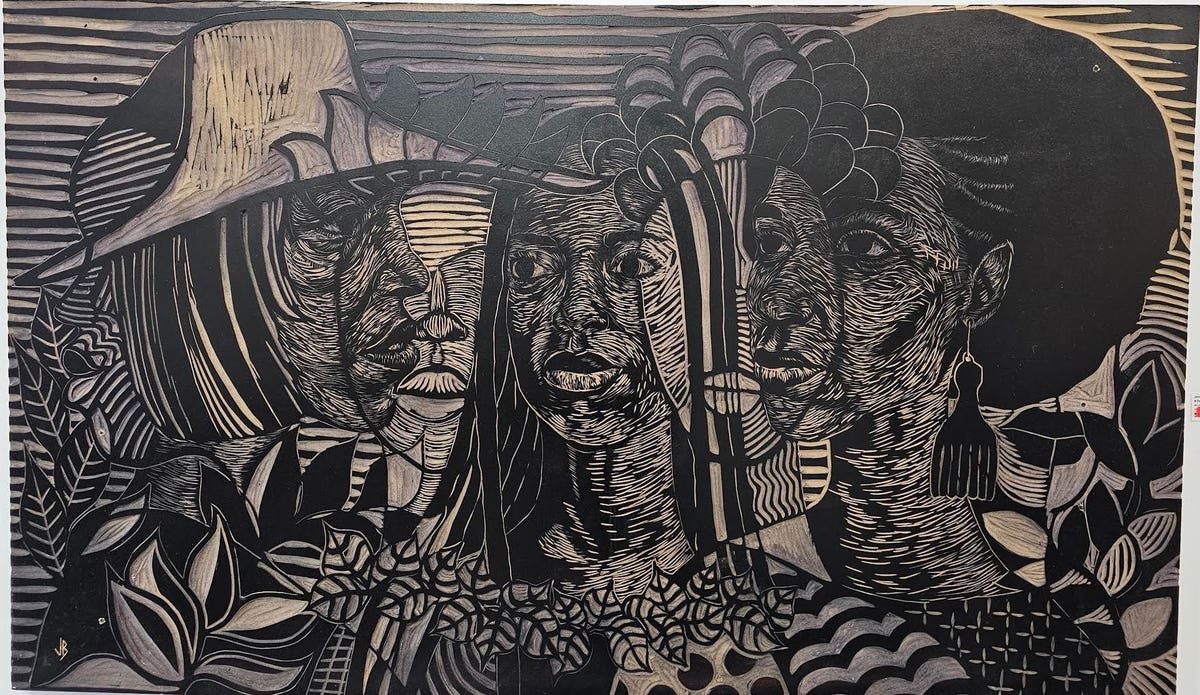

A young Black woman with long hair gazes slightly to the viewer’s left as she commands the center of the canvas, flanked by two older Black women, one wearing a hat and the other with an afro accentuated by a dangling wide-tooth hair comb earring. Two more female faces are slightly obscured as they overlap with the central figures. Another two faces emerge from the woman with the hat and the woman with the afro, evoking sisterhood and interconnectedness across generations. The women convey a sense of emotion, urgency, and intensity, forcing the viewer to confront the history, legacy, future, and power of Black women.

We marvel at the intricacies of the women’s facial expressions and the bold, graphic forms and elaborate patterns carved into the monumental woodblock on linen print. The size of the print underscores the scope of history being shared in the monumental visual narrative. A Council of Women by Jamaal Barber is among the works by more than 50 established and emerging Black artists showcased in the first-ever Fine Art Print Fair presented by Black Art In America (BAIA). Bookending the Better Days: Joy and Revolution exhibition, the fair will be on view at the Black Art In America Gallery and Sculpture Garden in Atlanta from August 11-12.

The primary figures are based on students from Georgia State University, where Barber — who was born in Virginia, raised in North Carolina, and moved to Atlanta in 2004 — recently completed his MFA in Printmaking, and this work builds on an earlier print, The Council, which highlighted Black men.

“We have to evenly tell the story of Black women, as much as we talk about Black men and how much they contribute. The Council and A Council of Women is the same concept of the shared experience. As much as we talk to ourselves, we also have our ancestors, our grandmothers, whoever else has set the tone about what Blackness should be and what whiteness is, and who makes you you,” Barber told me in an interview today.

Jennifer Mack-Watkins ‘Vanity II’ (2018) Silkscreen/Mokuhanga 22 inches by 26 inches

Barber, who is also a painter and began printmaking about 11 years ago, and Jennifer Mack-Watkins, a contemporary visual artist and illustrator whose work investigates societal conformity that isolates and confines individuals, are ambassadors for the fair.

“There is an economic argument because we’re making multiples and printmaking doesn’t have to carry the cost of every painting that has to carry the costs of studio space, materials, and the time the person put into making just one, so the painting has to be thousands of dollars in order to make up the costs of working. Printmaking is different. Each piece doesn’t have to carry all the costs, so it’s much more affordable,” Barber explained. “But there’s also much technical mastery, how the marks are being made, how it’s printed, how much time went into it. I think you can’t help but appreciate the amount of work that went into it. I think it’s a good way for people to enter the market. … It’s fascinating to learn about many different processes and how people are using these processes that have been around for thousands of years.”

Recognizing market demand, auction houses have been expanding sales of works of art made in multiple iterations, created through a transfer process, such as woodcuts, etchings, screenprints, and lithographs. Fine art multiples are not simply copies. Each print is an original and will vary at least slightly, even if not obvious to some viewers. Prints may involve arduous physical creative processes, and we can feel that intimate connection when we investigate the nuances. For example, Barber used a steamroller to create the large-scale A Council of Women.

“This inaugural Fine Art Print Fair is poised to be the country’s largest fine art fair of its kind focused on works by Black artists. The fair will provide visitors with the opportunity to learn about the intricacies of printmaking and a chance to get involved as collectors of fine art prints. With available works highlighting contemporary artists from around the country alongside master printmakers, we’ve also decided to center printmaker lead programming featuring Jamaal Barber and Jennifer Mack-Watkins, to emphasize the educational component. Again, the goal here is to highlight printmaking as a distinctive art form and to put forth a masterclass about collecting fine art prints as an asset,” said artist Najee Dorsey, CEO and founder of BAIA.

The need for a fair of this magnitude amplifying Black printmakers mirrors the need to update and inform art history to include women and people of color. The fair features works by wide ranging artists including Faith Ringgold, Kerry James Marshall, Chloe Alexander, Delta Martin, Nelson Stevens, and Mel Edwards.

Kerry James Marshall ‘Everything Will Be Alright I Just Know It Will’

Our gaze turns to one Black woman seated at her vanity and applying makeup in Mack-Watkins’ captivating Vanity II (2018), an assiduous silkscreen/Mokuhanga measuring 22 inches wide and 26 inches high. The artist, who earned a MAT from Tufts University, and a MFA in Printmaking from Pratt Institute, and who has visited Japan twice, works in the Japanese technique, Mokuhanga, which means “wood print” in Japanese. It widely adopted during the Edo period (1603–1868), when the country was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate (military government) and its 300 regional daimyo (magnets or feudal lords).

We marvel at the use of three colors, black, pink for curtains and the woman’s dress, and light brown for her skin, to convey a tour de force of movement, depth, texture, and drama, built by Mack-Watkins’ meticulous carvings. Her dress and the curtains are distinct, as an array of lines and shapes create shading and volume that guides our eye across the personal scene. The exploration of interior and exterior lives and worlds draws into the woman’s home, with only light flooding in from the windows, and no indication of what’s happening beyond her room.

“I’ve been playing around with this interior-exterior place, and how we see ourselves and how we navigate areas and spaces. When I was in Brooklyn, I didn’t do figures because I rgot tired of explaining (my work) to my class, and the professors and in my class who didn’t know who Elizabeth Catlett was, who Romare Bearden was,” Mack-Watkins told me in an interview yesterday.”My printmaking teacher would go to Italy every year to study the master printmakers, the great draftsmen, and the majority were white males. You have a whole book of great draftsmen and there’s no females in here.”

Mack-Watkins first created a smaller Japanese woodcut Vanity I as a commission for How to Get Away with Murder, a legal drama thriller series starring Viola Davis, one of the few actors who has been awarded an Emmy, a Grammy, an Oscar, and a Tony (a distinction known as EGOT) that premiered on ABC in 2014, and for Vanity II she decided to make a silkscreen and increase the size again.

“The lovely thing about silkscreening is you can work really small or you can work really big and you can cover it with color in a matter of moments,” Mack-Watkins said. “For that particular piece conceptually, I wanted to place the female in different environments. Later on, I have other woodcuts that show the female as a teacher in the classroom protecting children. In this case, it’s that one moment, just seeing yourself as beautiful, and just taking that moment to rest and see yourself as a beautiful human being. It’s about having those moments to recognize who we are as females and that’s what I was trying to capture in that work.”

Mack-Watkins began studying Japanese printmaking around 2012 at the Lower East Side Printshop in New York, taking a class with April Vollmer six times on Thursdays from 6-9 p.m. after working a full day teaching.

“I wanted to see the African-American female as a muse, and I decided to put brown figures in Japanese woodblocks,” Mack-Watkins said.

aith Ringgold ‘All the Power To The People’

Toni Morrison ‘The Moon and Sun by Delita Martin’