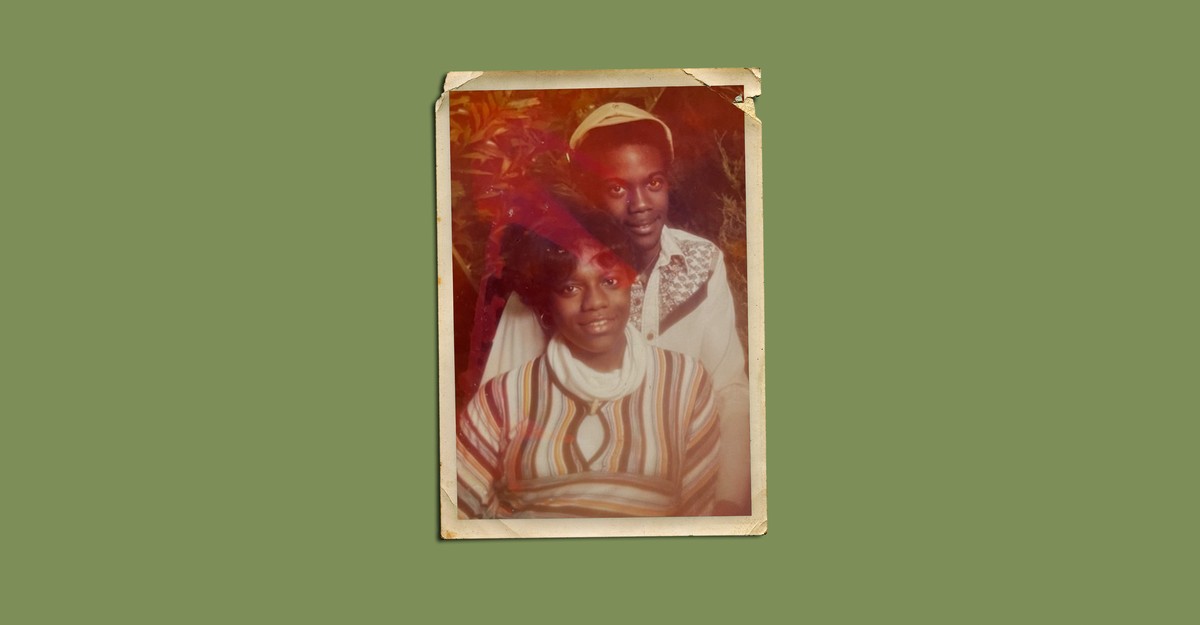

My father and mother met in the winter of 1976. I’ve seen photos. There they are, looking as young and untroubled as any two high-school students on a Friday-night date. Not yet parents, not yet weighed down with the responsibility of caring for four children, both are smiling, my father standing behind my mother, who sits on a stool with her head nestled into his chest.

My parents were introduced by my father’s cousin Larry, whose easy smile and welcoming personality marked him as a charmer. Larry and my mom attended school at J. O. Johnson High in Huntsville, Alabama, where he was two years ahead of her. Intrigued by the sly older boy, my mother dated him, but after the second outing, she opted to let him down easy by introducing him to her friend Wanda. Larry, in turn, suggested that my mother meet his cousin Esau, who went to school out in the country, at Gurley High.

On that first date, my mother was instantly drawn to my father’s tenderness. She would come to know him as outgoing and funny, but that night he acted shy and polite. They spent the evening parked at a drive-in movie. In the front seat, Larry and Wanda were hitting it off. Larry turned to Esau and said, “Go ahead, cousin, lean in and give her a kiss.”

My dad would have none of it. “I just met the girl,” he said. “I ain’t kissing nothing.”

After the date, my mom boasted that my dad was “the perfect gentleman.” She did not yet know that his tenderness came from grief, which lingered at the edge of his attempts at humor and charm. After a few dates, in a real show of vulnerability, he told her, “My father died a few months back. Right before he died, he told my mother that my brother Barney and I weren’t no good. I just thought that I would give you fair warning.”

Believing she could fix what is broken, my mother was hooked. Even now, knowing this man would become addicted to drugs and abuse her and her children, she is not clear on whether she should have heeded the warning, because their relationship resulted in the birth of her four children who brought her so much joy.

My dad was six feet tall, with an athletic build from his time as a basketball player, his brown skin a shade lighter than the ebony complexion I inherited from further up the family tree. He didn’t have the most expensive clothes, but they were always clean and well ironed. That tendency for cleanliness would remain until he died in 2017. According to my mom, when he was young he was “fine as the day is long, and all the girls wanted him.”

After they had dated for a few weeks, my father brought his new girl home to meet his mother, Wavon, and his grandmother Sophia. According to my mother, Sophia took one look at her and opined, “That is a very good woman right there. You don’t deserve her, Esau.” Turning to my mother, she said, “Laurie Ann, you seem like a nice girl. I would run. He’ll ruin your life the way his daddy ruined ours.” Used to barbs like this, my father didn’t defend himself. His normally wide smile tightened, and he lowered his gaze. My mother did not know how to process Sophia’s words.

They were just kids, and their courtship was brief. By the spring of 1977, my mother’s junior year, she was pregnant with my sister Latasha. They married in the summer of 1979, six months before my birth. My mother was not yet showing in the wedding pictures, but I was there, forming in her belly, when they exchanged their vows and first kiss as a married couple.

Everyone agreed that my dad was hilarious, the kind of man who has a nickname for every family member, friend, and neighbor. When he met you, he’d size you up and decide whether you were an Onion Head, a Potato Head, or even, occasionally, a Banana Head. Whatever he decided to call you, that was your name. The habit of renaming everyone he met is the one practice of his that I adopted as an adult.

A few years after their wedding, my father began working as a truck driver. He would return to the job whenever the terms of his parole did not prohibit travel out of state. Maybe he was drawn to it because driving carries with it an element of escape. He could be on the road, unconstrained by the demands of family and the limits of being poor, Black, and undereducated. He could be whoever he wanted to be to the other truckers he talked with on the CB radio. He could be gone for days at a time and return home a hero with money in his pocket.

When he came back, he told his jokes and bragged about his exploits, and we were all so happy to see him. When it was time for him to leave again, I begged my father to take me with him. I wanted to be his co-pilot, to travel with him and have adventures. He promised that one day he would take me.

When I was 8 or 9, old enough to insist, he finally relented.

I jumped up and down and ran over to my mom. “Did you hear? Did you hear? Dad and I are going on a road trip.” My mom smiled, happy to see me happy.

I packed my bag with a few outfits, my Optimus Prime Transformer toy, and my Bible. My mom came in to make sure that I had all the things I really needed, like my asthma inhaler, a toothbrush, and enough socks and underwear. While I prepared everything, my dad chatted with Latasha in the living room. She had no interest in going on the road, but she was excited to have a few days without her little brother getting on her nerves.

I had never left my hometown, nor had I ever been alone with my father for longer than it took for my mom to have a quick nap or go to the store. But I gathered my courage, doing everything I could to look like I was mature enough to handle an extended trip.

Just as I was about to head outside, he stopped me. “Son, I need to run to the store and get us snacks for the trip. Then I’ll come back and get you.”

“Sure, Dad,” I said.

While he was at the store, I reviewed the contents of my suitcase to make sure I had everything I needed. Then I went outside to wait for him. What should have been a 15-minute jaunt started to seem frighteningly long. Cars, delivery trucks, and the occasional SUV rumbled past our home, but no 18-wheelers.

After an hour, my mom came outside. She was gentle, calling me by my middle name in a silent nod to the fact that my given name, Esau, evoked too much pain. “I don’t think he’s coming back, Daniel.”

I wiped my eyes. “I know he’ll come for me. I know it.” I waited until the sun gave way, and then I wheeled my bag back inside. We did not see him again for months. He did not call or check in. One day he just returned home as if nothing had happened. I never asked to travel with him again.

There was no subtle shift or slow descent. His addiction sprang into my life fully formed, dividing the man in two. One man was the kind and funny person I loved, the other much more formidable. My mom tells me that he switched from marijuana to the hard stuff while on the road. “His trucking buddies introduced him to crack,” she said, “and he was never the same.” The drugs turned my father into something cold and terrible, a danger to my siblings, my mother, and me.

He would leave the house sometimes and return home in a rage. The slamming of the door and the barrage of profanities indicated a rough evening ahead. Inevitably, he found fault with something my mother or one of us kids had done:

Why is this house so fucking dirty all the time? Can you clean? Why does this dinner taste like shit?

And you, son, I hear you acting up in school. If I hear of that again, I am going to wear your hind out. You hear me?

What’s a matter? Why are you so quiet? You scared now? Why weren’t you scared when you were acting a fool in that school?

When he was high, he hit us whether we answered or remained silent. There was no clear path out of danger.

Kneeling at my bed every night, I prayed that God would help me grow so that I could defend my family. Too small and weak to fight back, I did what my mother taught me to do: I cried out to God. In the Bible, Esau and Jacob are brothers. Jacob is the chosen one. It is Jacob, not Esau, who wrestles with God during the night, trying to come to grips with his calling and destiny. But within the four walls of our Huntsville home, it was Esau Jr. who tussled with the Almighty.

I know many people who have struggled to believe in a God who allows such suffering, especially of innocent children. To them, my childhood pain is evidence that God either doesn’t care or isn’t powerful enough to help. Religion, they then conclude, is a false promise that keeps people shackled in fear, waiting for a salvation that never arrives.

Such criticism becomes even more urgent in Black contexts, where the question of why God didn’t intervene to end slavery sooner looms large. Where was God on the slave ships, in the cotton fields, in the courtrooms where innocent men and women were condemned to death for crimes they did not commit? Where was God when I was a child in need of his protection? There is no Black faith that doesn’t wrestle with the problem of evil.

My reply to these questions is: We who have suffered must have some say in how that suffering is interpreted. We won the right, through our scars, to discern the significance of what we endured. My grasp of that significance begins with my experiences of God when I was a child on my knees in front of my twin bed, hands clasped and eyes shut tight in prayer, repeating the simplest of prayers: “Help.”

In those prayers, God came to me not with logical explanations of the problem of evil but with his presence. When I prayed, a sensation of warmth that began in my chest moved throughout my body. The room seemed less empty. The lack of a speedy deliverance frustrated and perplexed me, but I never doubted my experiences of God. They were how I survived. God and I have been through hard times together; we have a relationship born of that intimacy. If any testimony deserves our attention, it is the large number of folks who believe there is no way to tell the Black story in the United States without affirming that God carried us through.

Those nights spent in fear set the trajectory for the rest of my life. They simplified my dreams: All I want is to love and be loved. I want to have children who go to school without shame and secrets. I never want the woman I love to have hands reaching for her with affection in one moment and malice the next. My father’s failures turned me into a family man at a young age.

Hate is such a simple emotion, and for long stretches of time it was all I felt. It provided me with a sense of clarity and moral superiority. I believed I had unraveled the world’s great mysteries by age 10. There are good guys and bad guys. My father is the latter; I will be the former.

One night when I was in seventh or eighth grade, my father returned home from yet another night of drinking and drugs and started making threats to my mom and sisters. Older now, I went to the kitchen and picked up a pot and a knife. Holding the knife in one hand and the pot in the other, I told my father, “You are not hitting anyone else in this house again.” My hands trembled. I was not sure what I would do if he decided to test my resolve. Instead he said, “Fuck you and this house,” and he stormed out.

Shortly after this incident, he was arrested on a theft charge. He cycled in and out of jail for the next few years. In his absence, my mother, my siblings, and I came into ourselves. We gained confidence. He wouldn’t be in a place to harm us again.

But his constant departures and brief returns meant that for most of my childhood, my mother and her four children—Latasha, Marketha, Brandon, and I—had to go it alone in a world made to swallow up poor Black families.

Whenever my grandmother Wavon saw me, she would call me over and say, “Old man Daniel prayed three times a day,” recounting the story of my middle namesake from the Bible. She told me that Daniel was taken from his homeland in Israel and carried off into exile in Babylon. Despite all the temptations of life in a foreign land, Daniel remained faithful to God, as evidenced by his habit of praying three times a day. “Have you prayed your three times?” she’d ask.

Wavon was sharing wisdom passed to her, the best guidance she had to offer. Our family, like Daniel and his companions, lived in a land surrounded by danger on all sides. My best chance of survival was prayer to the God who rescued Daniel from the lions’ den.

This article has been adapted from Esau McCaulley’s forthcoming book, How Far to the Promised Land: One Black Family’s Story of Hope and Survival in the American South.