As if on jubilant pilgrimage, Wake Foresters across generations made their way back to Venice this year to a house they once called home. Casa Artom, a magnificent 19th-century, two-story building facing the Grand Canal, was having a birthday, belated because of a pandemic but worth the wait for a glittering anniversary.

The celebration marked 50 years of Casa Artom’s place in University history. In 1971, Wake Forest acquired what was once the American consulate and opened its doors for the University’s first overseas residence for students to have a study-abroad semester in Europe. It was a game-changer.

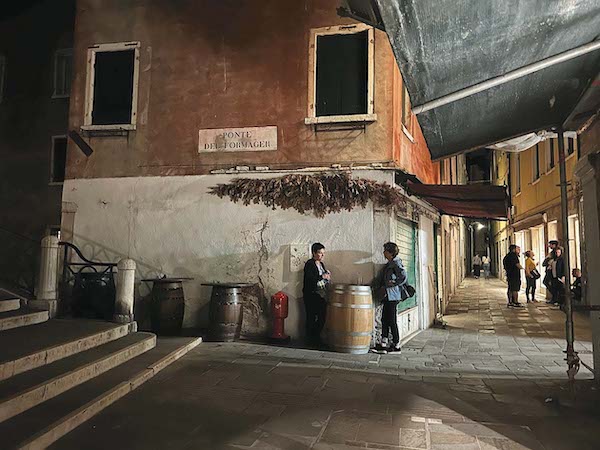

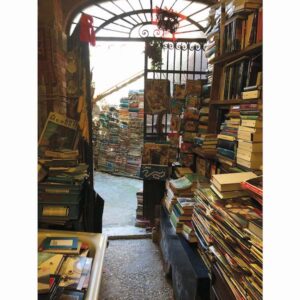

If you speak with alumni who studied at Casa Artom, you will hear without hesitation how the experience transformed them. They saw the world differently. They gained confidence. They immersed themselves into the rhythms of local life, down winding lanes, past the street cats sunning themselves on ledges or snoozing atop stacks in a famous bookstore. Above all, you hear alumni speak of the mentorship of professors, the constant sense of discovery and the breathtaking beauty of the art and architecture that enriched every moment of their study abroad.

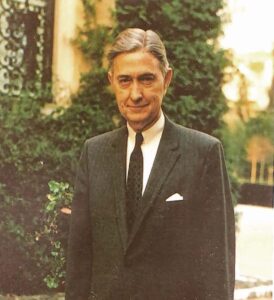

For decades, world-renowned scholar and professor Terisio Pignatti (D.F.A. ’76) taught our students art history at Casa Artom. This resident of Venice knew his subject, having written more than 60 books on art, most about Venice. (Wake Forest eventually named him Reynolds Professor of Art History.)

In 1963, long before his association with Wake Forest, he wrote a catalog’s introduction for a traveling exhibition from Venice to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. In it he extolled the work of artists who depicted Venice in the 1700s, the subject of the exhibition:

“Perhaps (Venice’s) image has been preserved because so much of the city’s past still remains close to us; gondolas and canals, crowded fondamente with lazy boys in the sun, and the Piazza San Marco … with processions of foreigners, and the boats bobbing along the Riva degli Schiavoni.”

He wrote as vice director of the Correr Museum in Venice, and while he was referring to artists, his message holds true for pilgrims like our Wake Foresters today. The familiar sights evoked memories that correspond to “an inner image” created by those long-ago artists’ portraits of Venice, he wrote, “a time beloved and dreamed about like a youthful fancy.”

Pignatti died in 2004, having imparted his lessons to our students and many more from other universities. Upon his death he was lauded for his “sustained infinite love of beauty” and his “indelible trust in the values of the universality of spirit.”

With this issue we toast Casa Artom and the guides like Pignatti who helped students and visiting faculty feel welcome in Venice. We hope you will enjoy the following collection of reminiscences and celebratory odes to Wake Forest’s home in a city that leaves anyone who visits with a lasting “inner image” of elegant surroundings, a time beloved and an appreciation for the universality of spirit.

— Maria Henson (’82), editor of Wake Forest Magazine

A Writer Remembers Casa Artom, Jim Barefield and ‘The Fine Line Between Mishap and Adventure’ in Venice

By Steve Duin (’76, MA ’79)

Those were the best days in the lives of Tancredi and Angelica. … When they were old and uselessly wise, their thoughts would go back to those days with insistent regret … .

Those semesters in Venice? They were the best days in our lives. We were young, foolish and blissfully unaware, but we had Jim Barefield in the house.

I don’t know that the program, or many of us, would have survived without Wake Forest’s storied history professor. When Barefield first took the plunge in the spring of 1973, the study-abroad experience was, like so much of Venice, unmoored, unkempt, unstable.

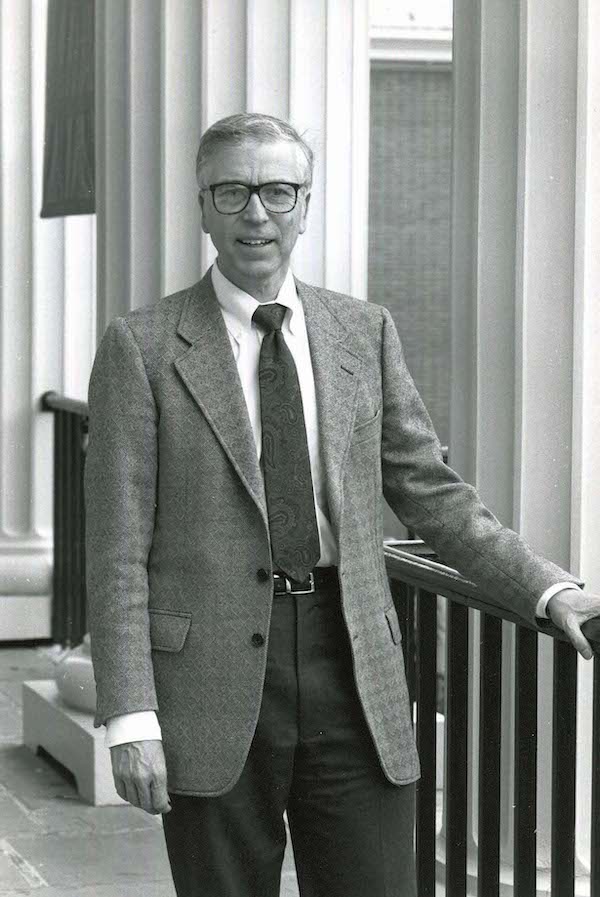

Professor Emeritus of History Jim Barefield, who has taken more student groups to Venice than any other professor

“A lot of the instability in ’73 was me,” Barefield concedes. He launched the History of Venice course when there was not yet a reliable history-of-Venice textbook, forcing him to explore and excavate the city every weekend to remain a half-step ahead of his 22 students. Casa Artom was so cold and damp that students once fed the fireplace with wood stolen from the Accademia Bridge, setting the mantel ablaze. And because the budget was as threadbare as the living-room furniture, Barefield was forced to assemble the students’ daily buffet — a curious feature of the program at the time — on $80 a week.

“At the end of that semester,” Barefield says, “I weighed 128 pounds.”

He rallied. He tightened his belt. He was inventive, resilient and self-effacing, and he came to understand that he and La Serenissima were a perfect match: Its history was a comedy of errors, and he had graduate degrees in comedic timing and the comic view. When then-Provost Ed Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93) needed an emergency replacement to teach in the fall of 1975, Barefield not only volunteered, but accepted 28 students, still the most in the program’s 50-year history.

“I think 19 of them became lawyers,” Barefield recalls. “They were somewhat litigious.”

He was a deft judge of character. As amused by his own quirks as he was by ours, he never held court. Barefield insists he had only two rules — “No one from outside the house inside without permission, and no drugs” — but there was always timely counsel. Intervisitation was still a divisive issue on campus that fall, and we wanted to write a letter to Old Gold & Black, gloating over how happily men and women were cohabiting on the Grand Canal. “For God’s sake,” Barefield said, “keep your mouths shut.”

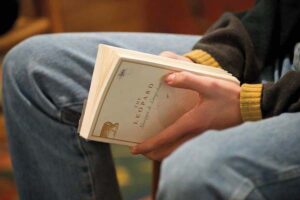

He knew how much help we needed when it came to living together. He schooled us regularly on the temperament of our hosts and blue-collar neighbors: “The Italians put up with things that a lot of people won’t … because they do things that a lot of people don’t.” He arranged class schedules so we might dodge train strikes on our way to Nice or Neuschwanstein. He not only introduced us to Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, but put the novelist’s best work to glorious use: In nightly competition with the house jocks, Barefield set copies of “The Leopard” on a table in the palatial downstairs hallway, then sent them cartwheeling with Frisbee flings from the ends of the hall.

Venice train station in the 1970s

All the while, Barefield was solidifying the relationships that allowed Wake Forest to finalize its purchase of the former U.S. Consulate and set its roots deeper into the mud of the lagoon. In the beginning, the University’s only real link to the city was Bianca Artom, the Wake Forest Italian professor who regularly returned to Venice, where she grew up, to keep the program afloat. Bianca’s nieces, Dora Sullam Levis and Anna Vera Sullam Calimani, were the house manager and Italian instructor, respectively, and Bianca served as grievance counselor to the long-suffering housekeepers, Luciana and Marisa. Barefield was a master of subtle diplomacy. He helped cement our connection to the Dorsoduro merchants, bartenders and gianduiotto architects. Despite his wretched Italian, he charmed many of the locals, no one more influential than Terisio Pignatti (D.F.A. ’76), who later became Reynolds Professor of Art History at Wake Forest.

Pignatti, the director of the Correr Museum in Piazza San Marco, was an eminent art historian who had authored dozens of books on Venetian artists such as Giorgione, Tintoretto and Titian. He could be gruff and imperial in his lectures on Renaissance art, but Barefield gained his confidence and his friendship. “Venice was his parish,” Barefield says. “He could do anything he wanted in Venice,” and that included the power to open so many doors for Wake Forest in the city. I mean that quite literally. In early December, we told Pignatti how much we’d appreciate one more morning with the glorious 15th-century paintings of Vittore Carpaccio’s Saint Ursula Cycle, which had been locked behind closed doors at the Gallerie dell’Accademia for weeks. Pignatti called the gallery director that afternoon and arranged the reunion.

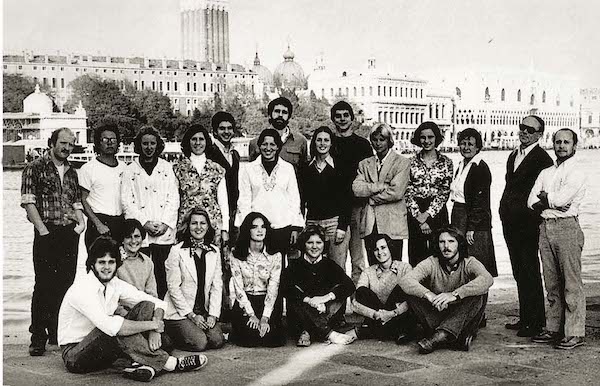

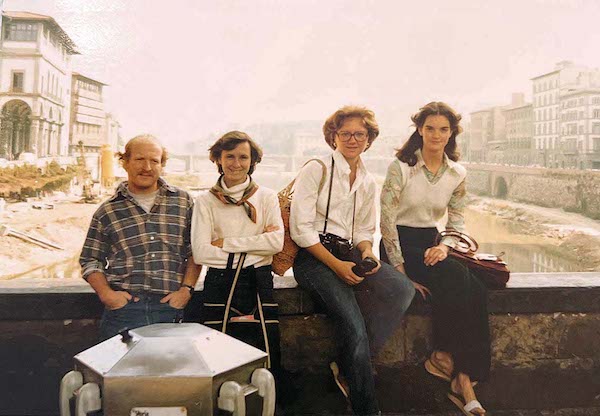

Fall 1977 Venice group with Professors Lowell Tillett (P ’76, ’78) and Anne Tillett (P ’76, ’78), standing second and third from right

Education had an intimacy and immediacy in Venice that I rarely found at Tribble Hall, and Barefield took full advantage. He required that we immerse ourselves in the maze of the city and its cavernous churches, sordid ambitions and colorful historians. “I was trying to rub your nose in Venice,” he says. “If you’re there, you might as well find out about the town. And it’s a complicated thing to find out.”

To stay sharp, he was forever taking notes, the rough draft of a blueprint he generously passed on to the professors who would follow him to Italy. “Barefield taught us how to teach Venice,” says Tom Phillips (’74, MA ’78, P ’06), who took leave from the admissions office in 1991 and 1997 to do so. “Venice appealed to his sense of irony. He saw it as a great lens to see how history works, how it permeates who we are and predicts our possible selves and futures.”

Those lessons endured. Trains often stop in the middle of nowhere. Laughter is just as essential as kindness. As St. Lawrence discovered, Barefield reminded us, sainthood sometimes requires that you end up “grilled, rather like a cheese sandwich.”

“Barefield is one of the people who truly shaped my understanding of the world,” says Doug Abrams (’76, JD ’79, P ’05, ’19), one of the future lawyers in the house in the fall of ’75. “He put his stamp on all of us, and I think it mattered to him to shape us. He took pride in it.”

His pride generally translated into affection. Even when Lucie Wall scaled the roof and followed a tree branch over the thin canal that separated Casa Artom from the Peggy Guggenheim Museum, Barefield remained calm and, ultimately, forgiving. Maybe he sensed that Lucie Wall-Stylianopoulos (’76) would continue that climb into a career as a Byzantine archaeologist. “What I’ve done with my life all started with him,” she says. “He was always there and supportive, yet he allowed me the independence to really explore Venice until I felt like it was my home and I could make of it what I wanted to.”

Or perhaps Barefield simply knew we needed to puzzle out certain things on our own. So much could go wrong. So much did; the history of Venice was proof of that. While we negotiated the fine line between accident and adventure, Barefield was caustic about our bids at bridge and spades, and far more gentle with our near catastrophes.

Small wonder we all remained close when we returned to Winston-Salem, where Barefield, in another glorious fanfare for an uncommon man, spent the next 10 years living, for $95 a month, in the Manor House at Graylyn. He would eventually return to Venice four more times. When he took over as program director in 1986, Barefield persuaded Wilson to invest another $50,000 annually into its mysterious budget. “That’s what I ran Venice on from 1986 to 1995,” he says. “I thought it was very nice of the administration not to question me much about it.”

And very wise. Barefield had a unique grasp of both Venice and the college students who came to visit. My only regret is that we’re not together there now, Frisbee in hand, “The Leopard” ducking for cover.

Illustration by Barbara Williams Humpton (’83) 1. Paul Diodati (’83) 2. Cynthia “Cindy” Ennis Mitchell (’81) 3. Beverly Church Blissit (’82) 4. Doug Blissit (’81) 5. Barbara Williams Humpton (’83) 6. Bob Clark (’82) 7. Edward Allen (’82) 8. Tom Pike (’81) 9. Mike Pontari (’82) 10. Theodora M. Drozdowski (’83) 11. Robert Jenkins (’81) 12. William “Bill” Davis (’83) 13. Margaret Ford Gregory (’81) 14. Joseph Davis (’80) 15. Robin Conte Isaf (’82) 16. John Spotts (’82) 17. David Davis (’81) 18. Beverly Perry Dillon (’80) 19. Mary Moorman Holmes (’80) 20. Virginia “Ginnie” Harvin Pitler (’82, P ’11) 21. Donna Snipes Schoettmer (’81, P ’12) 22. Kimberly Brewer (’81) 23. Anne Barnes (’81) 24. Jim Barefield

Steve Duin (’76, MA ’79) studied at Casa Artom in the fall of 1975. He is the author of eight books and a long-time newspaper columnist at The Oregonian in Portland.

Back to Top

Casa Artom at a Glance

In 1971, Wake Forest leased an 1828 palazzo, a former U.S. Consulate, at Dorsoduro 699 on the Grand Canal in Venice, with help from then-U.S. Ambassador to Italy Graham Martin (’32, LL.D. ’69, P ’84).

Then-Assistant Professor of Classical Languages John “Andy” Andronica (P ’89, ’92) took the first eight students — six from Wake Forest, none of whom had been abroad before, plus a student from Salem College and one from Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri — to the “Venice House” in the fall of 1971.

The U.S. House and Senate approved the sale of the consulate building to Wake Forest in 1974 for $250,000. If the University ever decides to sell the house, it must offer it to the government first for the same amount, plus the cost of improvements.

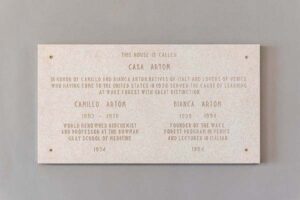

The “Venice House” became Casa Artom to honor the late Dr. Camillo Artom, a prominent Italian biochemist and medical doctor. Italian colleagues called Artom the “fat chemist” because of his groundbreaking work on how the body processes fats.

“There had been a heavy rain, but the sun was out, and my first glimpse of the Doge’s Palace and other nearby buildings, sparkling like the ‘fairy city’ that Lord Byron described, persuaded us that we had come to the place where Wake Forest should have a second home.”

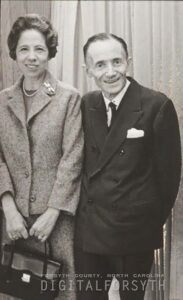

Bianca and Camillo Artom

Camillo Artom, who was Jewish, and his wife, Bianca Artom, had fled fascist Italy in the 1930s. He became chair of the medical school’s one-man biochemistry department, retired in 1961 and, in 1969, received the University’s first Medallion of Merit.

Bianca Artom was Casa Artom’s summer director and taught Italian language and literature on the Reynolda Campus from 1975 until 1990. After her death in 1994, Wake Forest honored her as the founder of the Venice program.

Peggy Guggenheim, next-door neighbor and art collector, was the first person to sign the guest book at the dedication of Casa Artom on July 11, 1974.

The original wood-carved University seal over the Grand Canal entrance came from Peggy Guggenheim’s friend, Countess Elsie Lee Gozzi, a native of Fayetteville, North Carolina, who ran high-end Fortuny fabrics in Venice and was married to Italy’s Count Alvise Gozzi.

The act of Congress authorizing the sale of the consulate building contains a provision that the University must provide office space to U.S. government employees from time to time, if requested. White House staff members used the building during presidential visits to Italy in the 1970s and 1980s.

Thanks to the generosity of Bianca Artom, 253 Artom Scholars have studied in Venice. “Bianca’s Italian Table” is a cookbook with her handwritten recipes.

Seventy-one faculty members from 20 academic departments have been resident professors. Retired Professor of History James Barefield, who taught in Venice for six semesters, holds the record.

“The Venetian venture has brought reactions of both enthusiasm and skepticism. Those who have partaken of it rejoice in its permanence. The skeptics doubt its permanence. To them I cite 12 centuries of Venetian survival.”

More than 2,000 alumni have studied at Casa Artom. More than 30 alumni met their spouses while studying there. Fourteen children of Casa Artom alumni followed in their parents’ footsteps to Casa Artom.

The man who helped Wake Forest find a home in Venice, then-U.S. Ambassador Graham Martin, had a daughter, Nancy Martin Lane (’84), and granddaughters Samantha Lane Englerth (’92) and Amanda Lane Long (’95) who graduated from Wake Forest. Nancy Lane studied Italian with Bianca Artom as an under- graduate. Englerth studied at Casa Artom in fall 1991.

The Professor is in … Venice

When Wake Forest decided to start a study-abroad program in the early 1970s, then-President James Ralph Scales looked first to Italy to realize his vision of professors taking students abroad for a semester to live and study in a residence owned by Wake Forest. Scales was fond of quoting poet Robert Browning: “Open my heart and you will see/Graved inside of it ‘Italy.’” The following scholars and keepers of the Casa Artom spirit surely share his sentiment.

John “Andy” Andronica (P ’89, ’92)

Professor Emeritus of Classical Languages

Casa Artom’s first resident professor, fall 1971 through spring ’72, spring 1981 and fall 1992

Andronica had studied in Rome but had never visited Venice when he was tapped to take students to the new “Venice House” in the fall of 1971. He was only 28, less than 10 years older than his students. Six Wake Forest students, none of whom had been abroad before, plus a student from Salem College and one from Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri, signed up for the nascent program. His wife, Grace Andronica, who had spent time growing up in Rome and Naples, taught Italian at the house. Their children, Matthew, 4, and Kristina, 2, went with them. Both later studied at Casa Artom. Andronica retired in 2008.

I’m not sure when the idea germinated in President Scales’ mind, but once it took seed, it bore fruit rather quickly. I remember Provost (Ed) Wilson (’43, P ’91, ’93) and Bianca Artom invited me to Reynolda (Hall) to chat about their plans to begin the program. That was in February or March of ’71, and the program was to begin that fall. The prospect of shaking the bushes to find students who would be interested and able to do it on such short notice was a real challenge. I announced it to my classes, and my colleagues announced it to their students.

We arrived, I think it was in July, and entered the palazzo on the long corridor entrance (now the library). Perched on a ladder — like Tiepolo or one of the great Venetian masters doing a mural — was Signor Abis, the holdover caretaker from the U.S. government, who was whitewashing a wall with a (small) brush. The problems of water absorption were very serious and created all sorts of damage. The walls were constantly peeling. Signor Abis knew what he was doing. It just took him a long time to do it.

He was quite a character. That first year, when we came back from Christmas holidays, the door (to Casa Artom) was bolted from the inside. We had no way of accessing the building. We had to wake Signor Abis, who lived around the corner. He had locked the place and bolted it shut from the inside. He had to get a ladder, scale the wall and let us in.

We had barely gotten settled when a young lady and two men with the local government arrived. The U.S. government had failed to pay taxes (on the building), and they were going to confiscate everything that was movable. I got in touch with President Scales, and he said, “Don’t do a thing. We have a contact in the embassy in Rome, and we’ll contact him. In the meantime, don’t let them take any furniture.” (The issue was resolved, and Casa Artom kept its furniture.)

Andy Andronica, far right, his wife, Grace, next to the woman in the red vest, and their children, Kristina and Matthew, front, with students in spring 1972

A city official was taking the vaporetto to work one morning, passed by Casa Artom and noticed that the original wood-framed windows had been replaced with anodized aluminum. It was the opinion of the city fathers that the aluminum conflicted with the color of the sea and the sky, and we were given 30 days to replace all the windows. One of Bianca’s relatives was a very prominent Venetian lawyer. Through his intervention, the Venetians decided that it would be permissible if we would hire a painter who could simulate wood grain (around the windows). From the canal, it looks like it’s wood.

Peggy Guggenheim reported us to the local government for having an oil-burning furnace. Little did she know, the furnace rarely worked. We may have gotten two or three weeks out of it the whole year. We had a fireplace in the main reception room upstairs which was constantly burning. Wood is very difficult to come by in Venice. The students would go to the vegetable and fruit markets at the end of the day and ask for the wooden (produce) crates. They’d bring them back, break them up and put them in the fire. We (also) used the gas oven in the kitchen. We shouldn’t have done that, but I can’t tell you how many times we slept in the kitchen.

We had a special arrangement with a local restaurant about five minutes away, between Casa Artom and the Accademia Bridge that’s still there, called Trattoria Ai Cugnai (At the Relatives), owned by two sisters and a brother. We went to them and proposed a deal for a fixed price of 1,100 lira per meal (about $2 at the time) per person for a minimum five meals a week. They not only liked the business, but they enjoyed the company of the students, who were always well behaved and treated them with respect and courtesy.

The natives were impressed that Wake Forest was the first American education institution that offered any promise of a (long-term) program. They were drawn to Wake Forest. We got word that a group of troubadours was traveling in the northern part of Italy, and they were looking for a venue (in Venice) where they could present four Harold Pinter short plays. We didn’t have a stage, so we took all of the long tables in the classrooms and put carpeting on them, and that was the stage, in the long corridor (today’s library). Peggy Guggenheim was there, and (poet) Ezra Pound was there (shortly before his death).

The administration didn’t know exactly what was involved, and they can be forgiven for not knowing that. … Unless I had (already committed to) the second semester, I would’ve packed up and left because the challenges were many. But once we settled in, it was a wonderful opportunity for faculty and students to learn together.

The experience in Venice … maybe it’s the ambience, the mystery, the opportunities that are many and varied. It’s a vehicle for students to become enmeshed in the culture of a new and different place. Venice, in particular, is a gold mine of opportunities with such a rich history. Over the four terms that I had students there, I really don’t know a single one that came back quite the same way after having the experience of studying abroad.

Peter Kairoff

Professor of Music

Casa Artom program director, 1996-2021, and resident professor, spring 1995, fall 1999, fall 2013 and fall 2021

Kairoff first visited Venice in 1981 when he was studying in Florence on a Fulbright Scholarship. He and his wife, now-retired Professor of English Claudia Kairoff, taught at Worrell House in London in 2018 and helped start Flow House in Vienna.

You look at old paintings and then look out the window (in Casa Artom) and realize that that view is the same one that Canaletto might have seen or painted in the 1700s, and Carpaccio a couple hundred years before that. It’s thrilling in a deeply moving way to be in a place where the vibrations of the past are still resonating even as modern-day life unfolds before you. … You start to see, not the ghosts of the past, but echoes of the past.

There’s a word, palimpsest, that refers to old manuscripts, often written by monks, in the Middle Ages. The parchments were precious, so if they needed to reuse one, they would scrape the words off one and write the new text. Sometimes the shadow of the early words shines through. I feel like Venice is a palimpsest sometimes. The modern “text” is right there. You see the shops and the tourists and all the boats going by. But if you look underneath it, you can see the shadow of all those other centuries of life.

It’s so different from anywhere else. You’re suddenly taken out of everything you know, and you’re plopped into this other world. Then when you go back to your old world, that looks weird to you now. You realize that the world can be a lot of things and not just the way you always thought it had to be. That’s one of the most precious gifts that we give our students: seeing the possibilities that the world can have.

One of the big changes I’ve noticed is the sense that studying abroad, you really had dropped off the edge of the world. You would call home once, maybe twice, and send these slow letters. Now, sometimes our students will fly home for a wedding over a weekend. We’re more connected now. The newness and specialness of being in Venice for a semester is less frequently found. But for some students, it is just as special and rare being out of the country for the first time.

The real preciousness of Casa Artom is that the students live there. They’re not visiting. It’s not a hotel; it’s their house. They are Venetians. The location is unsurpassed. Every picture you see of Venice, every ad in every magazine and every clip of every movie set in Venice, there’s Casa Artom in the background. There are a number of (university) programs (in Venice), but none of them, to my knowledge, owns a house or facility for undergraduate programs.

The neighborhood around the house has changed quite a bit in the last 25 years. There are fewer and fewer local residents and more and more tourists. For students, living in the house, shopping for their own food, looking out the windows as the boats float by as they’re doing their homework, is a real and privileged experience in Venice. Even the wealthiest families don’t have that. If you stay in the grandest hotels, you’re still a visitor. At the end of every semester, students feel like the house is theirs.

Every student has their own Venice. A lot of students come back and say to the next generation of students, “You have to do X, Y and Z.” And then the next students do J, K and L. It might be playing soccer with the locals. It might be learning to row gondolas at the rowing club up the street. It could be a particular pub that they like. They all discover their own talismanic experiences.

We have a nice system where Venetian university students come to Casa Artom and work with our students on projects. It could be something about the environment or ecology or immigration or water management or visiting museums (to study art). They become experts together. They talk in English. They talk in Italian. They make friendships that can become long-term friendships.

Venice is more different than any other place. It’s transporting. It’s magical. You’re in this place where the 20th and even the 19th century seems to have never quite made it.

Alessandra Beasley Von Burg (P ’14)

Associate Professor of Communication

Current Casa Artom program director and resident professor, fall 2014 and spring 2023

Von Burg is a native of Northern Italy. Her husband, Associate Professor of Communication Ron Von Burg, taught a lifelong learning course at Casa Artom in summer 2023. Their son, Josh Beasley (’14), studied at Casa Artom in 2012.

Casa Artom is both a palace — a grand, beautiful, gorgeous palace on the Grand Canal with the Guggenheim Museum as our neighbor and the 15th-century Ca’ Dario on the other side — and a home. For students, after a few weeks, it really feels like home, even if it is this grand place that makes you feel like you’re living in a fairy tale.

Venice is a city of contradictions. It’s beautiful, but the wonderful parts can also be the difficult parts. There is a peacefulness to Venice, in the water and the boats. But at the same time, it can be very challenging. Over time, the unique experiences become part of the charm, but at first it can be overwhelming.

Professors Ron Von Burg, right, and Alessandra Beasley Von Burg, in back beside him, reunite at the gala with students who studied in Venice in 2014: from left, front row, Emma Dolgos (’16) and Tee Urquhart (’16); back row, Hannah Duane (’16), Chelsea Bellomy (’16) and Samantha Larsen (’16).

This is a time (for students) to grow, to push themselves beyond what’s comfortable. Students never come and leave as the same person. Being in another country challenges you in ways that you never thought possible. There’s no such thing as reading a book or watching a movie and thinking you know a country. Venice is unique; there’s no other city in the world like it.

— Faculty memories as told to Kerry M. King (’85) of Wake Forest Magazine

Back to Top

Same Place, Different Time

By Kerry M. King (’85)

Casa Artom changed these students when they called it home. As alumni, they reflect on how their time at the house influenced their careers and their lifelong appreciation for art and culture.

Mark Robertson (’78)

Charlotte

THEN: Psychology major

Semester in Venice: Fall 1977 with then-Professor of Romance Languages Anne

Smith Tillett (P ’76, ’78) and then-Professor of History Lowell Tillett (P ’76, ’78)

NOW: Adjunct professor, Gardner-Webb University in Boiling Springs, North Carolina; retired principal, Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools

Returned to Venice with his wife, Halina, for their 10th wedding anniversary in 1989

Why did you want to study in Venice?

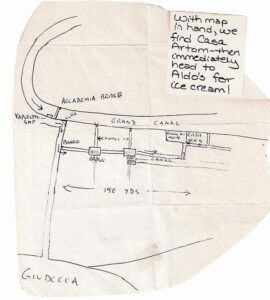

I had originally wanted to go to Venice because my girlfriend at the time was going. Then she dropped out, but I decided to go anyway. I flew to Brussels and went to London and Paris, and then I took the train to Venice. I had instructions on how to get to the house, which were totally useless. It was foggy and rainy. I could hardly see because of the fog. One of my friends came out of the fog quite by accident, and we greeted each other and went to the house. I was not “traveled” at the time, … and the whole trip to Venice was a real eye opener.

What is your favorite memory?

What is your favorite memory?

The Tilletts came down one night — all the men were on the bottom floor and the women on the top floor — and said they had been invited to a party for (University of) Warwick from Coventry, England, and would anyone like to go? One of my friends and I went to the party, and it was a lot of fun. I met my wife (who was a student at the University of Warwick) there. The only problem was, I started on the wrong end of the bar, and by the time I worked myself around to her, she was pretty sure she didn’t like me. She was in a pensione (apartment) by the Accademia (museum). She and I hit it off eventually and fell in love.

What are some other memories?

Tom Hayes (’79) and Kate Cochrane Rush (’78). Photo courtesy of Tom Hayes

Peggy Guggenheim was still alive, and she would walk her dogs. No one ever talked to her because we were afraid to. She’d teeter along back there with her little dogs.

I was a millionaire for the first time in my life, because it was 880 lira to the dollar. And I had just over a million lira when I first got there. I called home one time all semester because it was the biggest rigmarole you’ve ever seen. You had to go to this public phone and wait in line. (I remember) mailing those little light blue, Par Avion, fold-up letters.

Professor Terisio Pignatti. Photo courtesy of Tom Hayes

I remember our record player in the kitchen. We had five albums, and I remember three of them: “Born to Run” was a necessity at the time, “The Best of the Allman Brothers Band” and Tom Waits’ “The Heart of Saturday Night,” which is a real bluesy, sad, sad record. You could tell what people were feeling when they put on their record of choice.

We liked to go to Trattoria ai Cugnai (restaurant) for supper because it was the closest one, and I had no money. You could get a fixed-price meal for, I think it was 3,000 lira. So, for less than $3 you could get a helping of spaghetti or just a bowl of soup for 1,000 lira at the most. I lost a lot of weight, but I lived much healthier.

I remember (art historian) Dr. (Terisio) Pignatti (D.F.A. ’76) took us to the church where the Tintoretto paintings are. That was fantastic. Titian’s “Assumption” (of the Virgin) was new to me. And I really enjoyed seeing art in context versus seeing art in museums.

Doug Scofield (’78), Ann Robinson Austin (’78), Judy Pazdan Lytle (’79, PA ’82) and Mary Martin Kozlowski (’78, P ’08)

How did the experience change you?

I consider it one of the watershed moments of my life. It changed my perceptions of people and cultures. In a funny way, it informed my work with Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools in low-income, predominantly African American and Latin American schools. The study of culture is different from studying “right” or “wrong.” It’s the way people do things. It’s the way you interact with people. It’s making contact with human beings whatever their ethnicity or their culture.

Doug Schaller (’89)

Philadelphia

THEN: Art history major

Semester in Venice: Spring 1987 with then-Associate Professor of Classical Languages Robert Ulery

NOW: Works in business development for an architecture firm, MGA Partners; formerly a dealer in contemporary art

Returned to Venice on his honeymoon with his husband, David Barquist, in 2015 and has visited numerous times for the Biennale that focuses on contemporary art

Schaller

Do you recall your first impressions when you arrived in Venice?

Western Europe had a deep freeze, and Venice had a large snowfall. It was eerily calm and quiet. Venice in the ’80s was a much less intense environment (than today). The cruise ships that came later really changed the tourist industry. Venice was always a playground for the wealthy, but it wasn’t quite as ostentatious.

What do you remember about living in Casa Artom?

I don’t know how a professor would ever figure out how to get the right mix. Many of us were in an Italian class together. Rob (Ulery) knew how to choose, I think, gentle, really lovely individuals. He’s a soft, quiet person, and maybe that’s why he picked who he did. I was so young in some ways and very unformed, not worldly. I had been to Europe (but not to Venice) in high school, and I was coming in with a strong interest in the arts and history. Our cohort had a very strong group of Reynolds and Carswell scholars. They were ambitious, and they were already in a scholarly sort of channel. I really appreciate that now in a way that I didn’t think about at the time.

Is there a moment or experience that especially stands out?

There’s a great exhibition hall, Palazzo Grassi on the Grand Canal. The space (restoration) was designed by a woman named Gae Aulenti. She also did the Musée d’Orsay (in Paris) at roughly the same time. Both of those museums made such an impression on me professionally. There I am at 19, experiencing a rethought museum or exhibition space. That is critical for how my ideas about design for exhibitions (and) museum collections have always impacted me.

What other experiences do you remember?

A beloved outing that became a Sunday routine was a late afternoon visit to a church near St. Mark’s, San Zaccaria, with one of Giovanni Bellini’s great altarpieces.

Robert (Ulery) did something very wise. He planned a study trip to Rome and Naples during Carnevale to get us out of that craziness. We had an audience with the Pope. Chris Ryan’s (’88) family were strong Catholics and had some kind of connection (through a friend to the Vatican that allowed the group to receive third-row seats). He (Pope John Paul II) prayed for Wake in English and Italian, maybe Polish.

How did the semester impact your life?

You’re trying it on for size … in terms of self-identity. Who are you? At 18, 19, 20, that’s still in formation. What an amazing place to be when you start to really define that, to do it in a city that is about art, architecture and history and to do it with students that are scholars and future scholars. What is the life of a scholar? What is an academic, and is that for me? Is that where I would find myself? Venice really solidified a lot of that because it was intense; it was more in your face. It was all around you — work, study, sleeping, playing.

What’s it been like going back to Venice over the years?

Arriving by train, each time I’ve done that, it feels like I am a student once again.

Natalie Harvey (’94)

Hilton Head Island, South Carolina

THEN: Art history major

Semester in Venice: Fall 1992 with then-Professor of Classical Languages John Andronica (P ’89, ’92)

NOW: Director of cultural affairs, town of Hilton Head Island

Why did you go to Casa Artom?

Natalie Harvey (’94) with Elizabeth Hammond Burch, who attended Wake Forest in the 1980s and wishes she could have studied at Casa Artom. She attended the gala with her husband, Bruce Burch, her son, Elias Burch, his wife, Tiffany Marie Morales Burch (’13), and Tiffany’s father, Michael Mosal (P ’13); Tiffany Burch studied at Casa Artom in the summer of 2012.

I had friends who had studied abroad and lived with families, but that didn’t really appeal to me. I was interested in spending time with other Wake Forest students who I didn’t necessarily know and having that dormitory experience, although the most beautiful dormitory on the planet. I was looking forward to spending time getting to know the city instead of being a tourist.

What was it like arriving at Casa Artom for the first time?

I had traveled for a couple of weeks beforehand, and I had so much luggage. I remember the struggle of getting luggage on and off the vaporetto. I got off at the Accademia Bridge vaporetto stop and then had to walk up and over a couple of tiny little canals, and then you come to the doorway (of Casa Artom). Opening the door was jaw dropping. You could see straight out to the canal.

What are some of your memories?

My favorite thing to do was just to take a walk: “I haven’t been down this road,” or “I haven’t seen this side of town.” You can’t get too terribly lost. You’re eventually going to find a sign that points you back to a place you recognize. One of the things that always made me laugh is you’d get to a corner, and it (sign) says “Piazza San Marco,” and the arrows point both ways.

You’re going to hear a lot about Thanksgiving from anybody that was there in the fall. Grace (Andronica) knew the drill on finding a turkey, but it was too big to fit in our little Casa Artom oven. So, she arranged to have it cooked at the bakery around the corner.

Natalie Harvey and her mother, Pat Harvey, at Taverna San Trovaso

There wasn’t a whole lot to watch (on television). But strangely enough, we had a DVD or a VHS tape of “Beauty and the Beast.” I’m not kidding, we probably watched it two or three times a week, and we could sing all the songs and recite the entire movie.

Anytime I hear “Nightswimming” or “Man on the Moon” (by R.E.M.), I remember being in Venice with my friends, exploring the city, going out to the Santa Maria della Salute in the evening to watch the gondolas and boats go by.

Having the opportunity to study with Dr. (Terisio) Pignatti and then meeting some of the world-renowned experts in their fields and seeing behind the scenes at museums and galleries really cemented my art history major. We did an ancient civilizations course with Dr. Andronica. Even though it wasn’t something that was up my alley, (because of) his passion for it and his enthusiasm, you couldn’t help but enjoy it. Then, having the chance in Rome to see the places that we had learned about and discussed really stuck with me.

How did the experience change you?

I had traveled quite a bit with my parents. The traveling part was not new to me, but spending time there getting to know how the museum world worked and being in a place that is so ancient and yet so preserved did influence me. That certainly influenced my future studies and perspective on historic places.

Alice Green Brown (’03)

Atlanta

THEN: Economics major

Semester in Venice: Fall 2001 with then-Professors of Economics Dan Hammond (’72, P ’08) and Claire Hammond (P ’08)

NOW: Founder of social enterprise GoodSteps; formerly a lawyer

Returned to Venice on her honeymoon with her husband, McKnight Brown, in 2011 and visited Casa Artom, where the resident professors were, serendipitously, the Hammonds

What was it like being there during the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks?

Alice Green Brown on the Grand Canal in fall 2001

There were Italian policemen at our door for a day or two. No one was sure if there were going to be other incidents around the world, and they wanted us to feel safe, which was really kind. Venetians were very sympathetic and supportive and flew their flags at half-staff. The next day, Dan Hammond gathered us to talk about everybody’s feelings and fears and to pray for everyone who was affected. The Hammonds let us, and our parents, know that Wake had put together an evacuation plan if necessary. I think the whole experience made us bond more quickly as a group.

What are some of your favorite memories?

We watched “Seinfeld” over and over. There was a box set at the house, and that was the only English program available. I feel like I could quote all the episodes by heart.

We saw some amazing art. I enjoyed it, but I’m sure my roommate, who was an art history major, enjoyed it more. She probably didn’t find the conversations I had with vendors about the economics of converting to the euro quite as interesting.

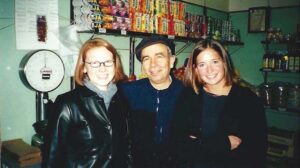

In 2001, Brown, right, and Susan Edwards Groves (‘03) with a store owner

We took turns cooking for the whole group. My friend, Susan Edwards Groves (’03), and I decided to do a Southern meal, which was quite the undertaking because they (vendors) didn’t have any of the ingredients that we needed. We had to be creative, and we had some interesting conversations with the Italian food vendors. We made fried chicken — we had to buy several whole chickens — and we couldn’t figure out anything to dip it in other than corn flakes.

Grocery shopping in general was an experience. In Dorsoduro, right down the little calle (street) from Casa Artom, was a cheese and milk vendor (Stefano). A little bit farther down was the bread vendor (Bruno). They were only open during very interesting hours that never overlapped with each other. Otherwise, you’d have to go to Billa, which was the supermarket. The ethnic food store, which was very hard to find, had some American food such as ketchup and peanut butter.

Jonathan Sumrell (‘03) and Brown during an acqua alta

We would go walking at night a lot because all the tourists were gone. At the time, Venice still allowed cruise ships to dock there, so the population would increase by the thousands during the day. It could be a zoo in and around the tourist areas. But at night there was nobody there. We got to see St. Mark’s Square, Rialto Bridge and all the most Venetian places with no crowds. We sort of felt like we owned Venice.

The room I shared was the only one facing the Grand Canal on the bottom floor. It was a constant chorus of motorboats, vaporetti (water buses) and gondoliers singing or talking to the people in their boats. During “acqua alta,” when the water overflows the canals, the canal actually came into our room. If you needed to go to the restroom in the middle of the night, you’d better get your boots on.

Did the experience change you?

Yes, definitely. Partially because of Sept. 11 and partially because I left the country for the first time. It made me more adventurous and more adaptable.

Maria Antonia “Tonis” Montes (’11)

Washington, D.C.

THEN: Political science major and Italian and Latin American Studies minors

Semester in Venice: Fall 2009 with then-Associate Professor of English Dean Franco

NOW: Senior program officer, United States Institute of Peace, Washington, D.C.

What do you recall about seeing Casa Artom for the first time?

Tonis Montes in 2023

I didn’t realize it was on the canal and right next door to the Guggenheim Museum. Della (Hinman ’11), Olivia (Milroy Evans ’11) and I were really lucky because the room that faces the canal was the room with three beds. So, we claimed the best room in the house. It was really surreal to open the window and hear the water from the canal and see the boats going by. When we got to Venice, it was the annual regatta. There’s a little dock in the front of the house, and we went out there, and boats were going up and down the canal. It was just such a beautiful moment to see the regatta.

What are some of your favorite memories?

I remember our Italian art classes, taught by Agnese Chiari, a renowned Venetian art historian. She would show slides of Renaissance art in the classroom and then take us to see it in the museums, and it would just come to life.

2009

Dean Franco instituted family dinners at the house on a Thursday or Friday night that a group of students would prepare. Those family dinners were really special. I also remember Thanksgiving. There was a restaurant, San Trovaso, in our neighborhood that would roast the turkey for us. That was really nice to have a little piece of home.

There was a coffee bar that we all loved called Bar da Gino. I remember getting a cappuccino there on the weekends, and it was where we had a lot of caprese sandwiches between classes.

One of my favorite parts of the city was the “pointed end” of our neighborhood, Punta della Dogana. I would sit there in the afternoons and look out at the canal. There was a beautiful church, Santa Maria della Salute. You could see St. Mark’s from that viewpoint. That was one of my favorite places — and going to the “Gugg” (the Peggy Guggenheim Collection next door), walking around St. Mark’s and the Rialto (Bridge) and the fish market.

We had an Italian literature professor, Shaul Bassi, who was a professor at Ca’ Foscari, the Venetian university. We were paired with Italian students at Ca’ Foscari for a peer exchange to practice Italian and English.

We had an Italian literature professor, Shaul Bassi, who was a professor at Ca’ Foscari, the Venetian university. We were paired with Italian students at Ca’ Foscari for a peer exchange to practice Italian and English.

Around the holidays, we had a class to make our own Venetian masks for Carnevale. We got to choose a mask and paint and design it. I still have that mask.

How did the experience change you?

We were studying identity in our English classes, how identity shapes culture, what it means to be a stranger in a foreign city and what that means for your own assimilation into a new culture. Currently, I do a lot of work on peace and security and how identities are shaped by conflict and war. I think back to a lot of what we discussed in those literature courses.

On a personal level, it affirmed a sense of wanting to explore different countries. I travel a lot for work now. I attribute my love for travel and interest in different cultures from my time being abroad, and how grateful I am for that time to have adventures and how you learn about yourself and about others.