This Hispanic Heritage Month, we’re telling the untold stories of women, women of color and LGBTQ+ people. Subscribe to our daily newsletter.

There’s something about a bridge. For one thing, it doesn’t belong to any one person. If it does its job, it gives a neighborhood new life. More than anything, it literally and figuratively connects communities.

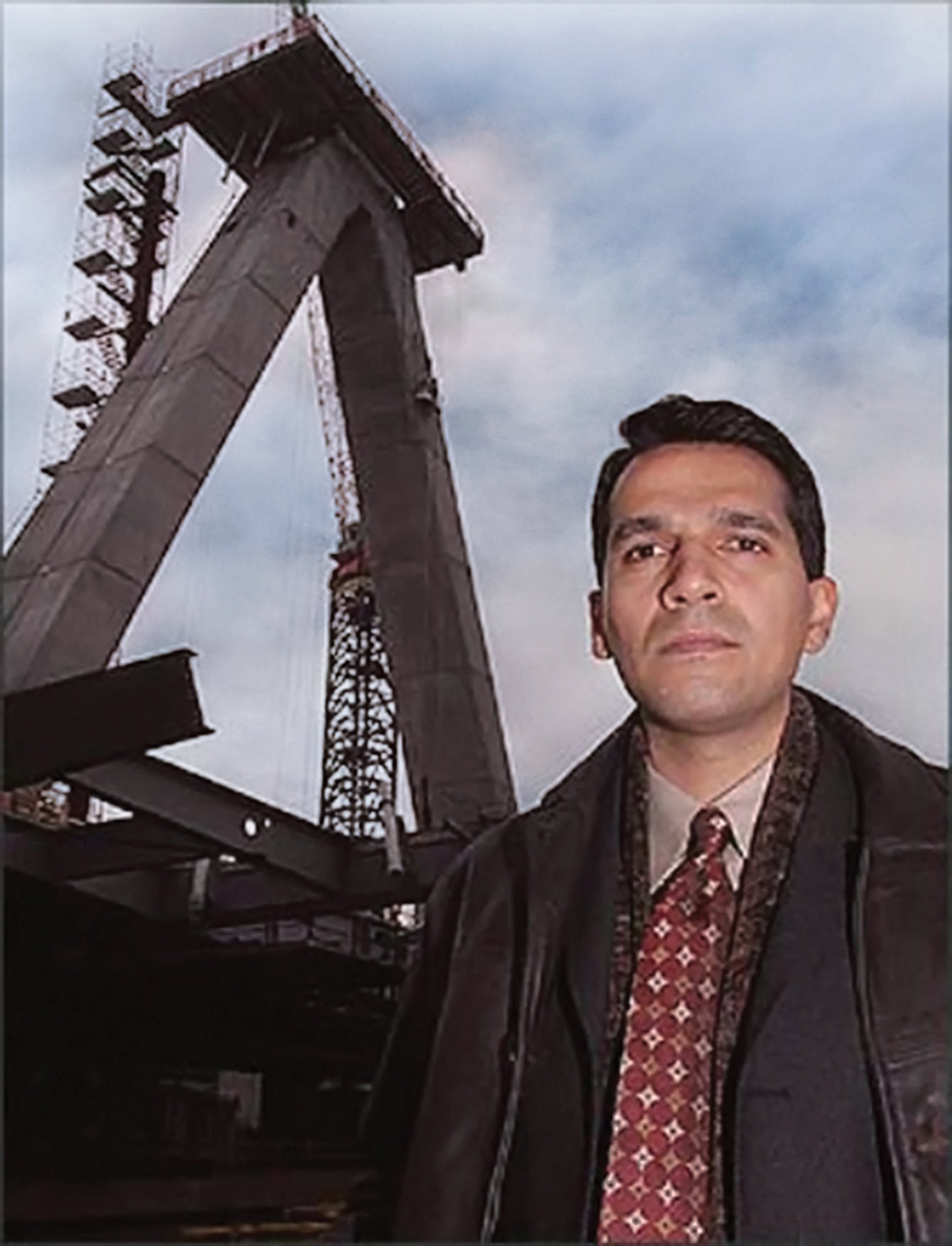

Architect Miguel Rosales, 62, walks the bridges he designed decades ago and is filled with pride. His story is an unlikely one — a gay immigrant from Guatemala reshaping the skylines of major cities all over the world. But he doesn’t need people to know who he is, to attach his name to the bridges they love.

“I see other people walking on it, biking on it,” he said. “It’s very satisfying to me … I think bridges can be very transformational and they can really change a town or a city. To me, they are more important than individual buildings.”

Thirty years ago, Rosales helped change Boston with a drawing and an idea: make the bridge that would connect Charlestown to the West End a cable-stayed bridge, a towered bridge held up by cables and cheaper to build than traditional suspension bridges like the Golden Gate Bridge.

Boston was in the midst of the Big Dig, a massively over-budget and behind-schedule project to reroute part of Interstate 93 underground. Rosales had been appointed to a 42-person committee to tackle a redesign of the current bridge.

Rosales was young, largely untested and fresh out of graduate school at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he studied urban and environmental design. He had migrated from Guatemala City in 1985 and been on a mission ever since to understand what makes great infrastructure. He traveled to Europe to study bridges and major public works projects, poring over plans from countries that invested in roadways in ways the U.S. simply didn’t.

Now, sitting with this committee in Boston, he had a chance to prove something. By February of 1991, the committee had drafted a plan for the bridge: 16 lanes of traffic, weaving through a series of loops suspended over the water.

Charles Redmon, a member of the Bridge Design Review Committee, told the Harvard Gazette later that residents on both sides of the river complained that it was “the ugliest monster anyone had ever seen.”

“I don’t think anyone could find anywhere in the states a larger, more ungainly spaghetti mess of a roadway,” Redmon said.

Young Rosales had a different idea.

“That area had been kind of abandoned for a long time and was never really attractive,” he said.

A sleek and modern bridge was needed. Renowned Swiss engineer Christian Menn, who was about to be drafted onto the project, agreed. The crossing needed a cable-stayed bridge.

“I immediately start to think that it will go well with the sailboats and kind of the marine environment there because the cables kind of look like rigging,” he said.

In 1992, Rosales was appointed lead architect of the $115 million project. Eleven years later, workers completed the Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge. It was instantly hailed as one of the city’s most iconic structures.

The white bridge is unmistakable at a distance. Its two upside-down Y towers resemble delicate string instruments, stretched across Charles River. It’s constantly the subject of photographers, whether on Instagram or Etsy prints or postcards.

Boston is an old city, at least in American terms. The city has spent generations celebrating its colonial traditions — the three-story wooden house where Paul Revere set out for his famous ride, the replica boat where revolutionaries angrily dumped shipments of British tea into the harbor, the townhouse Louisa May Alcott rented on Pinckney Street in Beacon Hill. The bridge stands as a modern icon in an old city.

“I think there is that tension between old and new that is very real and held in high high relief,” said Max Grinnell, who teaches urban studies at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, as he walked through the Back Bay, a historic neighborhood of brick sidewalks and multi-million dollar brownstone homes.

Architectural commissions rule many parts of these downtown neighborhoods. In many areas, a resident can’t legally repaint their own front door the same color without approval, for fear that a fresh coat will violate the neighborhood’s historic charm.

But skyscrapers have risen in the distance. A modern-day city has sprung up, and the Zakim Bridge is a visible symbol of that.

“I think [the Zakim Bridge] speaks to the hope of cities as a new start or a new opportunity,” Grinnell added.

It is a city where residents still prize lineage, where some still boast of family trees extending to the Mayflower.

Rosales arrived in the United States at age 24 without any of that. His family didn’t have a lot of money growing up. His father was a pharmacist, and his mother stayed at home. His childhood had been difficult.

“I was discriminated [against] because people felt like I was too feminine, too soft, too introspective, too shy, all of those things that people associate with a stereotype of being gay,” Rosales said.

He wasn’t out, and when he arrived in Boston in 1985, it still didn’t feel safe to be openly gay. He had too many other things working against him.

“For me to succeed, I had to be much better than anybody else,” he said. “First of all, I was foreign and Latin, but bridges traditionally are done by White men.”

The success of the Zakim Bridge opened a new world for Rosales. In 1996, he came out as gay. The following year, he founded Rosales + Partners, his own architecture firm.

Rosales’ projects grew in size and budget and took him all over the world. In 2004, he completed the $120 million Centennial Bridge in Panama. He designed the George Washington Carver Bridge in Des Moines, Iowa. He spearheaded the plans for the $700 million Interstate 74 Mississippi River Crossings in the Quad Cities in 2022.

Around the same time that construction finished on the Zakim Bridge, something else big happened for Rosales: He met a guy who was also really into architecture and design. John David Corey loved restoring historic homes. He was curious about bridges, too.

“He has learned a lot about bridges,” Rosales said. “I show him all of my designs.”

This year, the couple celebrated 20 years together, five of them married. They live in one of Boston’s strict, historic and expensive neighborhoods: Beacon Hill. Rosales, who helped build the modern Boston, loves how old the neighborhood is.

“It’s the most beautiful neighborhood in the city,” he said. “My opinion is that it’s very consistent and is very well-preserved.”

Rosales sees no contradiction between a love of modern architecture and a reverence for the old. In 2019, the Boston Preservation Alliance awarded the Longfellow Bridge rehab project with its Preservation Achievement Award, noting that the project stayed true to its 1901 aesthetic while meeting modern standards. Rosales had served as architect on the project.

Rosales says the same principles apply across generations and across continents.

“I think if they were ugly they would not be the landmarks,” he said. “Beauty sells. If something is beautiful, people gravitate to it and they don’t even know why.”