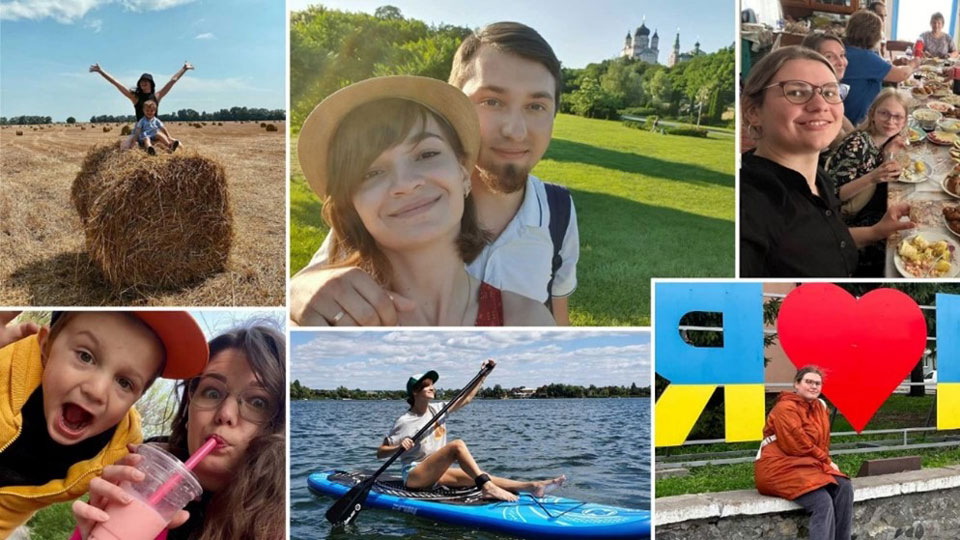

Tokyo-based NHK World news director Kateryna Novytska hails from the Ukrainian capital Kyiv. She regularly speaks with her family and friends to see how they’re coping with the ever-present threat of attack by Russian forces, and the impact it has on their day-to-day lives and well-being. Recently, she arranged a group online call with three close friends to ask them a range of questions submitted by NHK viewers.

Life in Ukraine

Kateryna:

“First of all, if you feel that you are in danger, you can stop the interview immediately.”

Olha:

“I only slept three hours today because of the air defense alarm and the explosions. Kyiv has been like this almost every night for the past month.”

Olha lives in Kyiv with her husband and 4-year-old son.

Olha says she no longer uses bomb shelters during missile attacks.

Olha:

“I have to walk 15 minutes to the nearest shelter, which is the subway station. Just imagine: 3:00 a.m., I walk to the subway carrying my child in my arms and sit there until about 5:00 a.m. And I can’t sleep all this time. Better to spread out the futon in a relatively safe hallway, so I can still sleep a little. While lying down, I can hear explosions and falling debris from missiles. I’m just praying, ‘Don’t fall on my house.'”

Olha worries that the attacks are traumatizing her son.

Olha:

“My son woke up and said, ‘Hey mom, another Russian missile? It really pisses me off.’ A child who’s not even five years old says, ‘It pisses me off.'”

Another friend, Olya, also lives in Kyiv, but on the day of the call, she was in her car with her husband, driving west to a region that’s further from the threat of aerial bombardment.

Olya:

“Every night, being woken up many times and sleeping in the hallway … I can’t do it anymore. Even when there’s no siren, I can’t sleep until around 2 o’clock, because I’m thinking that the siren might go off again.”

Olha:

“Yes, yes, same story.”

Olya:

“I don’t get enough sleep, so I don’t feel alive. I’m pretty depressed, my work efficiency is bad.”

The third person in the group call is Anna. She used to live in Japan, but after the invasion began, she returned to live with her family just outside Kyiv.

Kateryna:

“Do you also think about going somewhere safe?”

Anna:

“I don’t think so. I came back to Ukraine to live in my hometown.”

Kateryna:

“Don’t you regret going back?”

Anna:

“I have no regrets. Now that I am here, I feel better mentally. I am very relieved to be able to feel the same as my family now. When I was in Japan, I worried about my family and blamed myself for being safe, and not helping anyone.”

Adapting to the new normal

All three women say they’ve become inured to the attacks on their homeland.

Olha:

“It may not be good, but we’ve gotten used to this situation. For us, this is the new normal. There are missile attacks at night, and in the morning we return to normal life. Normal life goes on … in between the attacks.”

Olya:

“I realized that the things I used to think of as problems aren’t such a big deal, like not being able to do my job on time or having an argument with someone. The real problem is that you and your family’s lives are always in danger. Also, the very concept of death has changed for me. Before, I thought death was abstract and even romantic because of the influence of movies. Now when I hear the word ‘death,’ all I can think of is fear and that my life doesn’t belong to me anymore … it can so easily be taken away.”

Anna:

“I think I feel more connected to my family than ever before. I used to think, ‘I don’t need anyone’s support, I can support myself.’ Since the war started, I’ve come to feel the importance of connection to my family and friends, and that we can do a lot to help each other.”

Finding peace in a war zone

All three women have mechanisms they use to cope with the violence.

Kateryna:

“Olya, what do you do to calm down?”

Olya:

“My way of calming down is to walk a lot. Recently I’ve been trying to take a walk every day after work.”

Kateryna:

“Anna, what makes you happy?”

Anna:

“Every Sunday, I take lessons in ikebana — the Japanese art of flower arrangement. I immerse myself in it, and I don’t even notice time passing. I sort of recharge myself this way.”

Kateryna:

“Olha, are there any times when you feel happy these days?”

Olha:

“When I pick my son up from kindergarten and walk home with him. I buy him ice cream and get myself a latte and we walk slowly together. I’m enjoying doing this, because I know it’s a moment that I will never experience again.”

The enemy over the border

Kateryna:

“One viewer asked: ‘Do you still support the Ukrainian government, which continues to resist Russia?'”

Olya:

“I want people to imagine: One day, the person in the apartment next door suddenly kicks in the door, walks in, and says, ‘It’s not your apartment, it’s mine. I’m going to live here from now on.’ And then he will eat everything in your fridge, rape your wife, and take your children. This is our situation. What would you do? You can’t just say, ‘Go ahead, take the apartment, use whatever you want.’ No! We can’t give up on our land, our people, our history.”

Anna:

“It is not the government that has chosen to resist Russia, but the people of Ukraine. Russia is denying our Ukrainian identity. That’s why we’re fighting.”

Kateryna:

“But isn’t it possible that protecting life and surviving is more important?”

Olha:

“Russia won’t let us live! I was in a village occupied by Russia for a time, and I heard people talking about the horrific violence perpetrated by Russian soldiers.”

Olya:

“Many foreign media outlets still write, ‘This is Putin’s war.’ But it’s not like this. I think everyone has a choice. Even if Russians are forced to go to war, nobody is forcing them to rape women, shoot up houses, or write happy comments on social media under reports about tragedies in Ukraine. That’s why I get angry when people say that the war between Russia and Ukraine is Putin’s war.”

Kateryna:

“This is another question from a viewer: ‘Do you think you’ll be able to talk to Russians again after the war is over?'”

Olha:

“No. How can we communicate? If we look at the example of World War Two, well, it may be possible after about three generations. But this generation and the next one … I think it’s 100 percent no.”

Olha has a cousin in Russia. She says her relationship with him has broken down.

Olha:

“I got a call from him after the invasion started. He said, ‘Pack your bags and come to Russia.’ Then he started saying things like ‘Zelenskyy is a clown president’ and ‘Russian soldiers only attack military targets.’ I told him, ‘You don’t know anything.’ Then we got into a fight and I said to him, ‘From now on, forget that you have relatives in Ukraine. No more messages or calls. I won’t contact you either. I’m going to forget you exist'”.

Away from the fighting

Over the past 18 months, Ukraine has become synonymous with conflict and destruction. Kateryna asked her friends to describe some more positive images of their country.

Kateryna:

“Where is your favorite place in Ukraine?”

Olya:

“My favorite place is where I’m heading now — the Carpathian Mountains in western Ukraine. This is my oasis. It recharges my mind and body. The Ukrainian mountains are incredibly beautiful, with lots of greenery and stunning views.”

Olha:

“When you think of Ukraine, you think of the fields. You drive through these fields, seeing combine harvesters and tractors here and there. It’s so beautiful. There, out in the fields, I feel really at peace.”

Anna:

The thing I find really beautiful in Ukraine is the steppes. You look out and they seem to go on forever. The sky is so huge, and the expanse is amazing. Ukrainian spring is also amazing. But to feel it you need to spend a winter here too. After you suffer a bit from the severe Ukrainian winter, it’s amazing to feel nature being reborn.

Kateryna also asked her friends to discuss their favorite aspects of Ukrainian culture. Olya nominated Vyshyvanka, the national costume of Ukraine, which is a traditional embroidered blouse or shirt.

Olya:

“Our national costume, Vyshyvanka, is fascinating. The patterns of embroidery differ from region to region. Every motif and color has its own meaning and history. So interesting and so beautiful!”

Anna chose Kosiv painted ceramics, a traditional form of pottery that originates in Kosiv, a city in western Ukraine. It’s characterized by its colors — green, yellow and brown. It was registered as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2019.

Dreams of a happier world

Kateryna asked her friends about life after the war.

Olha:

“I tried to think about what I’ll do when Ukraine wins the war. First, I’d buy a bottle of sparkling wine to celebrate. Then I’d like to travel overseas with my husband.”

Anna:

“I’d like to invite all my foreign friends to Ukraine. I want to show them Kyiv. I fell in love with Kyiv again. I want everyone to see it. When the war ends, please come!”

Olya:

“First of all, I’d want to let it truly sink in that the war is over. I’m used to living with constant stress, so I’d want to really appreciate the fact that peace has come to my home. Also, I want to travel safely inside Ukraine. I really want to go to Crimea.”

A message to the readers

Kateryna’s friends had some parting comments for those who read this.

Anna:

“I don’t want the world to get desensitized to the situation where Ukraine is under constant attack. Even if only one person dies, that loss of life should never be overlooked. We can’t sleep normally. We can’t live normal lives. Please don’t forget that we’re suffering at this very moment. I also want people to know that our military personnel are ordinary people like me, who also need humanitarian help.”

Olya:

“Please don’t think of us as ‘pathetic victims’ or ‘poor things.’ We are normal people just like you, who are protecting ourselves and our homeland. I want you to understand our situation, and support us so that we can win as soon as possible and return to a happy life full of dreams.”

Olha:

“We all have the same daily thoughts. Like, what should we have for dinner? Or for me — my son will start elementary school next year, so I need to find a teacher who will get the best out of him. If I forget the war even for a moment, I feel like I did something wrong. Sometimes I despair and want to cry. I can’t think about the future, but I have a child, so I have to.”

On the surface, these three women have the same day-to-day concerns as many young adults across the world, but looking deeper, their lives reveal the indelible marks of war’s influence — broken sleep, traumatic memories, and constant anxiety, but also resilience, and a determination never to give up.