Sometime in the early ’70s, Nora Ephron negotiated a deal for her essay collection Crazy Salad: Some Things About Women over a plate of hot pink steak. Nestled under the ficus trees, Ephron was one of many authors attending power lunches at the Four Seasons restaurant in Manhattan during publishing’s golden age — or as some consider it, the “good old days.” While the business of mass-market books has since lost a glitzy sheen, recent developments in the “big five” publishing houses, which include Penguin Random House, Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, and Simon & Schuster, and beyond suggest an awakening of the spirit. In February, unionized HarperCollins employees returned to work after a three-month strike won a pay raise for their lowest earners. In July, New York magazine reported that Penguin Random House was “cleaning house” as legendary longtime editors took buyouts en masse. As a younger generation ascends into coveted roles, AI, social media, and political conservatism are among the unknown variables affecting what books enter the world. The new professionals have a few demands.

The most pressing is their salaries. With historically abysmal salaries, this guaranteed a book industry stocked with monied bohemians; today, more than 80 percent of publishing employees are white. But union efforts, start-up presses, and a demand for storytelling diversity all indicate the collapse of barriers to entry. The push for transparency created the viral #PublishingPaidMe campaign and a spreadsheet where thousands of authors share their advances. According to a 2020 report on publishing’s workplace diversity, 75 percent of respondents said that their employer had increased equity efforts that year, which often included entry-level pay raises.

Riding this wave of sea change, Shondaland is focusing on three women in the industry who represent what’s exciting about its future. Fanta Diallo, a publicist at W.W. Norton, is expanding the idea of readership. Sophia Kaufman was instrumental to a new labor contract win as an assistant editor at Harper Perennial and a HarperCollins union steward,. Deborah Ghim is an editor at Astra House, a start-up publisher taking risks on unexpected titles.

Our conversations weren’t linear — in the best way possible — with winding digressions about their latest projects. And it’s this passion that will keep a business as fickle as this one alive.

Fanta Diallo, publicist at W.W. Norton & Company

For most of her life, Fanta Diallo didn’t know that working in book publishing was an option. Now a publicist at W.W. Norton & Company, she has the sense that this is “exactly what I’m supposed to be doing,” she says.

Graduating in 2020 with a marketing degree, Diallo was on track to enter the high-powered world of business consulting when she realized that she was choosing a path for all the wrong reasons. As the financial supporter for her family, making money was a concern, but she resented having to compromise. When she took an editorial internship, she found a second job. When she went full-time, she freelanced on the weekends.

She was routinely the only Black person in meetings, all of which were on Zoom because it was the middle of the pandemic. “I felt very disconnected from the publishing industry, even if I was enjoying the work,” Diallo says. But when she came across Rest Is Resistance by Tricia Hersey, it was a revelation. She worked on the manifesto by the Nap Ministry founder while in editorial at Little, Brown and Company, then developed its press campaign after she transferred to the publicity desk. In an all-staff email during Mental Health Awareness Month, Diallo invited her colleagues to share in her new perspective.

“The ‘strong Black woman’ trope has long been represented through figures in books, film, and television — and certainly in reality — and showcases a near-superhuman ability to persevere in the face of extreme struggle and trauma,” Diallo wrote. “In reality, this trope is a deflection. … By choosing to prioritize our collective mental health and encouraging others around us to do the same, we are saying farewell to the insidious trap of grind culture.”

The concept of — or demand for — rest does not mean neglect. She’s currently in the middle of a major campaign for MCU: The Reign of Marvel Studios, which chronicles the superhero movie’s triumph over Hollywood. “It would just be irresponsible, frankly, for me to say I’m going to end at 5 today because I want to, when I have an inbox of emails that need responding,” Diallo laughs. Dan Gerstle, senior editor at Liveright, a Norton imprint, calls Diallo one of the hardest working people he’s ever met. “If I didn’t know better, I would think she had been working in publishing for 15 years,” he says. Norton is employee owned, and Diallo says the difference is palpable. Holding a financial stake in the company raises the interest in the success of each book. At a “big five” publisher, there is more likely an inflexible chain of command.

Part of Diallo’s hiring was tied to a new initiative, the “Well-Read Black Girl Library Series,” publishing debut works of fiction by women of color, a previously scant minority in literature. An analysis by The New York Times found that of the 7,000 titles on their best-seller list since 1950 where they could identify the author’s race, 95 percent were written by white people. “For my entire life, I’ve inserted myself into white characters’ heads,” says Diallo.

Publicity might not hold the same rom-com-level intrigue for outsiders as writing and editing. But it’s critical to achieving the change that higher-ups say they’re ready for. Jennifer Baker, an author, editor, and host of the Minorities in Publishing podcast, wrote in an essay earlier this year that “DEI initiatives don’t automatically equate to better business practices. A diverse reading book club doesn’t translate to increased publicity or marketing budgets or detailed promotional plans.”

It used to be the case that Black authors needed a white publishing insider to push their writing into the market. Attention wasn’t paid to what non-white readers might want. Diallo is making detailed promotional plans for titles she would have wanted as a young Black girl who didn’t start buying books until her 20s. “Reading is intimidating. Books are intimidating,” she says. “I think a publicist’s job is to make them as accessible as possible.”

Sophia Kaufman, assistant editor at Harper Perennial and Harper Paperbacks

Before she had her own desk at a 200-year-old publishing firm, Sophia Kaufman was bouncing between gigs across Manhattan. She was a full-time manager at Book Culture on West 112th Street, where her favorite task was sifting through boxes of paperbacks dropped off by professors. In the mornings, she read submissions for The Paris Review. Recently, she heard of an agented writer who was shopping their book; it was a writer whose story she’d dug out of the slush pile and fought for its publication years earlier.

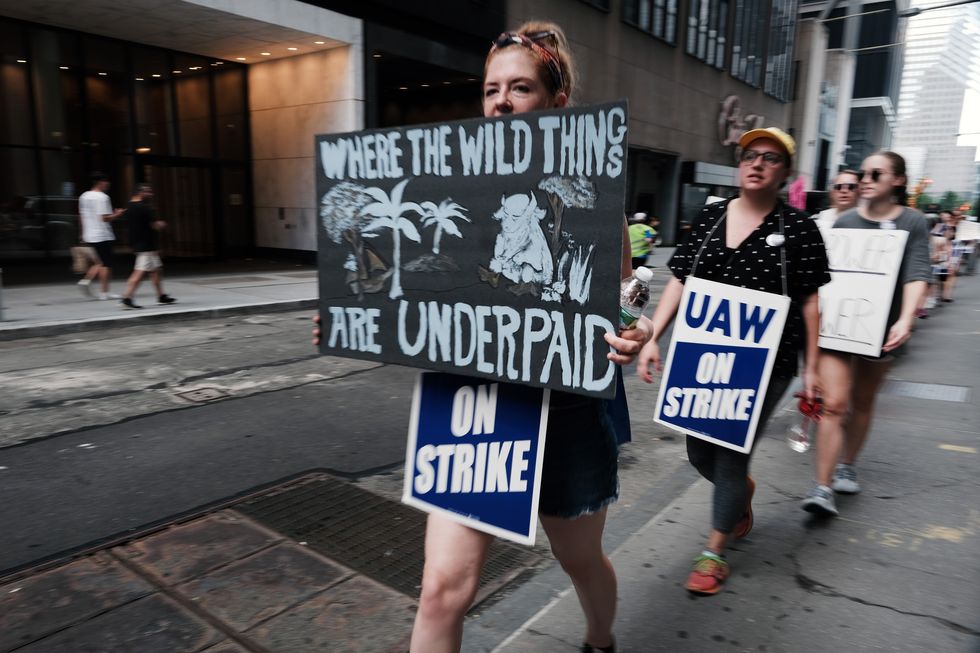

Kaufman has fought throughout her career, including for the right to have it. In November 2022, she and 250 other HarperCollins employees went on a labor strike, ceasing work to picket the company’s headquarters, where they were joined by prominent authors and industry peers who bore signs reading, “A series of unfortunate salaries” and “Working with books should not be a debt sentence.” Three months later, the union secured a new contract regarded as a success particularly in the realm of pay. The starting salary would be immediately raised from $45,000 to $47,500, increasing to $48,500 by the start of 2024 and to $50,000 by 2025.

Despite their wins, which were heralded as a new precedent for the industry, “there were some people who were maybe a little older who [during the strike] felt like, ‘We suffered, so they should suffer,’” Kaufman says. “But it’s not really comparable. … There are barriers to entry that are very, very obvious. These things are coming to a head.”

New York City employs 75 percent of the country’s publishing sector. A cost-of-living report on the city from earlier this year found that a minimum salary of $100,000 is considered necessary to afford housing, food, transportation, and some semblance of savings for the future. What are those who work with books to do when they make less than half of that?

“People are not going into book publishing because they think it will make them really rich,” Kaufman says. “People will keep going into publishing because they like reading and writing and stories. And not having to work a second job, or cut down on your groceries, or live somewhere with a lot of noise or a ton of roommates — these are choices that are dictated by your salary, and they affect how you can do your job.” Kaufman, for her part, still takes weekend Book Culture shifts. She also serves as a Harper union steward, fielding her colleagues’ concerns amidst return-to-office requests and wrongful terminations.

Kaufman’s voice rises as she tells me the link she made between what she saw as a strike captain and a ruffle at Vanity Fair in the 1920s: When management told employees not to disclose their salaries, Dorothy Parker and her colleagues painted their wages on signs they wore around their necks. Kaufman found that detail in You Might as Well Live, an out-of-print biography of Parker. In addition to daily tasks of editing, assisting senior staffers, taking agents to lunch, and reading new writing found in magazines like The Drift cover to cover, Kaufman analyzes the backlist of Harper Perennial, strategizing what titles they could reissue with a new introduction or a more modern cover.

But it’s Kaufman’s recent, contemporary acquisition that feels most in line with her ethos. The forthcoming debut novel from Jeremy Gordon, a longtime fixture of digital media, concerns a culture editor who, to stay ahead of journalism layoffs, decides to produce a podcast. After a shocking discovery, the editor ends up investigating his high school friend’s death. “There’s this sense, especially for writers, that if you can find something in your own life to turn into content, how could you not? There’s grief in that, and humor,” says Kaufman. “All of us, all the time, are pressured to hustle.”

Deborah Ghim, editor at Astra House

In another life, Deborah Ghim is a start-up founder in Silicon Valley, which is where she landed after college. She insists that she’s lucky to have found her way into working with books, and she can’t help describing her job in the language of romantic love. Discovering a gem of a manuscript is like having a crush; explaining the resonance of a book is like defining attraction empirically. Ghim declares online that she “will publish your book [at Astra House] and dedicate my whole stupid little life to you.” As an editor at the imprint celebrated for ambitious translations and experiments across genres, she means it.

“What is fun about being an acquiring editor, and also very tiring, is that everything that I can think of that will make a book succeed, and everything that I have not yet thought of, is my responsibility,” Ghim tells me. It’s like being the producer of a movie where the task is to help a story’s sumptuous inner life find its footing in the world outside of its narrative. “Everyone knows you want to get blurbs. You want to get reviews. You want a beautiful book jacket. Something that keeps me up at night is ‘What am I not thinking of?’”

Ghim faced a challenge with Dogs of Summer by Andrea Abreu, a short debut novel by a poet that was translated from Spanish to English. She thought it would have a chance if she attacked from a less expected angle: one of aesthetics. And this did not entail contracting a random vendor to pump out tote bags. Noting the Y2K nostalgia reverberating throughout culture that is naturally incorporated by Abreu, Ghim enlisted a Brooklyn-based jewelry artist she admired to make a limited series of friendship bracelets. The book transcended its lyrical lines to establish itself as a desirable object reflective of the psychology of girlhood. “I’m trying to get an American reader invested,” Ghim says. “Is that not like matchmaking?”

Astra House is a new player in the market, launching in 2020 as the U.S. arm of Thinkingdom Media Group, a Chinese publishing giant. (Ghim was recruited after four years at Farrar, Straus and Giroux, where her authors included Christina Sharpe and Virginie Despentes.) Astra’s small team has editorial freedom, a clean slate, and cash. With such a small and focused book list — the imprint publishes some 20 to 30 print titles annually, compared to Penguin Random House’s 15,000 — Ghim is defining the character of the press with every manuscript she acquires. “We’re not ourselves identifying as disruptors. But I think that inherently by being new in a very, very old industry, we are,” Ghim says. “There’s the idea that books in translation don’t sell. Maybe that’s true. We won’t really know until we give a book in translation as much of a budget or as much faith.”

A year after its U.S. release, Dogs of Summer’s pink and purple cover is showing up in GRWM TikToks and at a Manhattan singles book club. Another Ghim project, Esther Yi’s Y/N, has been shortlisted for the Center for Fiction’s 2023 First Novel Prize. The New York Times called her author Sean Michaels’ latest, Do You Remember Being Born?, “timely and lovely” and “quiet and thoughtful.” It’s timely now, but Ghim acquired Michaels’ book about a poet asked to collaborate with an AI years before.

With her latest puzzle, Celina Baljeet Basra’s Happy, out earlier this month, Ghim is breaking a book that has no precedent: a bildungsroman written in English by an Indian author living in Germany. The author isn’t worried. She calls her editor “a bright and brilliant mind, my favorite kind: sharp, quick-thinking, meticulous, with an amazing eye for the small things and the big picture, and an indefatigable passion for her books … Deborah Ghim is a genius.”

Greta Rainbow is an arts and culture writer based in Brooklyn. Follow her on Twitter @gertsofficial.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY