For a long time, Keenan White, 29, of Dallas, Texas, suspected he had paternal siblings, but he wasn’t sure until his mother saw his sister’s name on child support paperwork when he was 16 years old. Despite having limited contact with his father, White was eager to get in touch.

White had grown up witnessing the love his mother had for her 11 siblings, two of which had a different father, and her lesson for him was that there was no need to make a distinction. She urged him to contact his sister. “I never heard the term half-siblings growing up,” White says about his decision to reach out to his sister, who was a month older than him. “Whether we share one or two parents in common is irrelevant. That is just the way it is.”

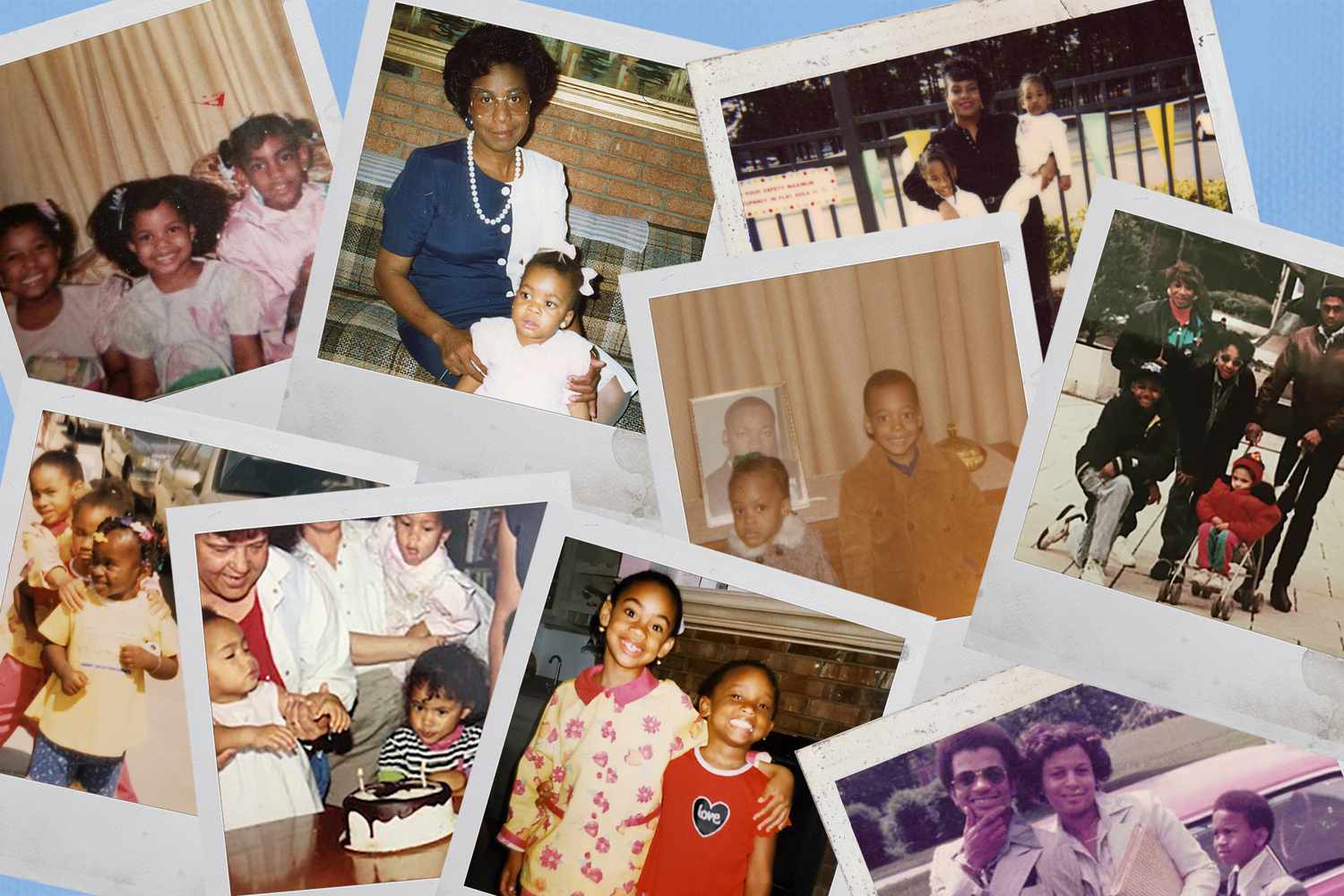

This sentiment is a nod to the unapologetically Black tradition of expanding the definition of family. In Black communities, even as language, land, and cultures separate us, we are connected by the tradition of love that doesn’t have to be based in biology. Gabrielle Union’s refusal to use the term ‘stepparent’ is an example of creativity in kinship. For as long as history can record, we’ve developed bonds with others, anchored in the belief that blood has never been a prerequisite for family. Even as the larger society worked hard to delegitimize us.

White’s sister welcomed him with open arms, and within a few days, he’d met all five of his paternal siblings. “It was the most magical thing for me. Seeing my mom be so close with all her siblings, made me wish I had a lot of siblings too,” he says, noting he has one sibling through his mother but always wanted more. “We were all so close in age. I couldn’t help but imagine how amazing it would’ve been had we known each other growing up and feel robbed that we did not get that opportunity.”

A History of Choosing Family Across the Diaspora

Hettie V. Williams, Ph.D., a historian, writer, and assistant professor of African American history in the department of history and anthropology at Monmouth University, says terms like “step-sibling” and “half-sibling” are rare in Black communities because fictive kin networks have been necessary for survival.

“Bringing a non-blood-related person into one’s family circle or kin network was a common practice out of necessity,” she says. “[It was] born of the chaos of racial enslavement and is a system that also speaks to the centrality of the group or family to African American society and culture.”

Williams says fictive kin describes non-blood-related family members like aunts or uncles who have been given honorific titles based on their closeness to immediate family or blood relatives. She says it is often based on the support they’ve given the family.

Scholars on Black American history note the importance of nonbiological and non-nuclear kinship for survival for enslaved Africans and their descendants. But the practice of Black communities embracing an expansive definition of family extends much farther than slavery. Black people across the diaspora continue to create bonds that aren’t based on biology.

Nicole Owuor, 25, of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, migrated from Kenya to the U.S. at 5 years old. She was 18 before she learned she wasn’t related to her cousins.

“It came up one day, and I asked my mom how she even met these people if they weren’t our family, and she said she met them at the bank and the DSW,” she says, recalling her mother’s story of reaching out to them after meeting at a bank because they looked—and were Kenyan. Her mother met her Aunty Daisy, who is Ugandan, while she worked at Bank of America.

“She invited them over and said, ‘your aunties are coming for dinner.’ They’ve been family for over ten years now. We’ve been to their weddings and spent holidays together,” says Owuor, adding most of her family members in the United States are African folks her mom met or those who came up to her after spotting her.

Being biologically related was irrelevant as they celebrated graduates, family cookouts and met more relatives from Uganda and Kenya.

It’s All Love

Dr. Raquel Martin, Ph.D., a psychologist, researcher, and writer who explores mental health, race-based stress, and racial socialization, notes that the tradition of defining Black families expansively reflects the sense of collective consciousness and responsibility Black communities hold, often developed in places like churches.

“I put family of origin and family of choice on equal ground,” says Martin. “So many of us have come out of situations where the fictitious kinship is all we have—and that’s okay,” noting the respect, love, and importance of the bonds is the same. She says the bonds can be especially essential for those with severed ties.

Alicia s.g. Freemyn, 38, who lives in Washington, D.C., says she and her wife often reflect on their experience building and rebuilding family bonds across biological and chosen contexts, especially when they think of the future they want for their toddler.

“We have known the precariousness of validating our relationships through institutions or as solely by blood, especially during histories of enslavement, and some of us from the rejection from our families of origin because of our queerness,” she says. “We understand family as more than nuclear; it is intergenerational and communal. We hope our child experiences family and community as a wide, creative net of love.”

Alicia’s comment highlights the potential of fictive kin as a tool of resistance to binary family designations, especially as society continues to devalue Black lives and families systemically.

Psychologist Dr. Raquel Martin, notes that nonbiological kin can be especially useful for those with limited access to, or who have chosen to cease contact with, their families. “The experience of clinical work and working with predominantly Black and underserved families shows individuals can still thrive through psychology and health without the typical nuclear family.”