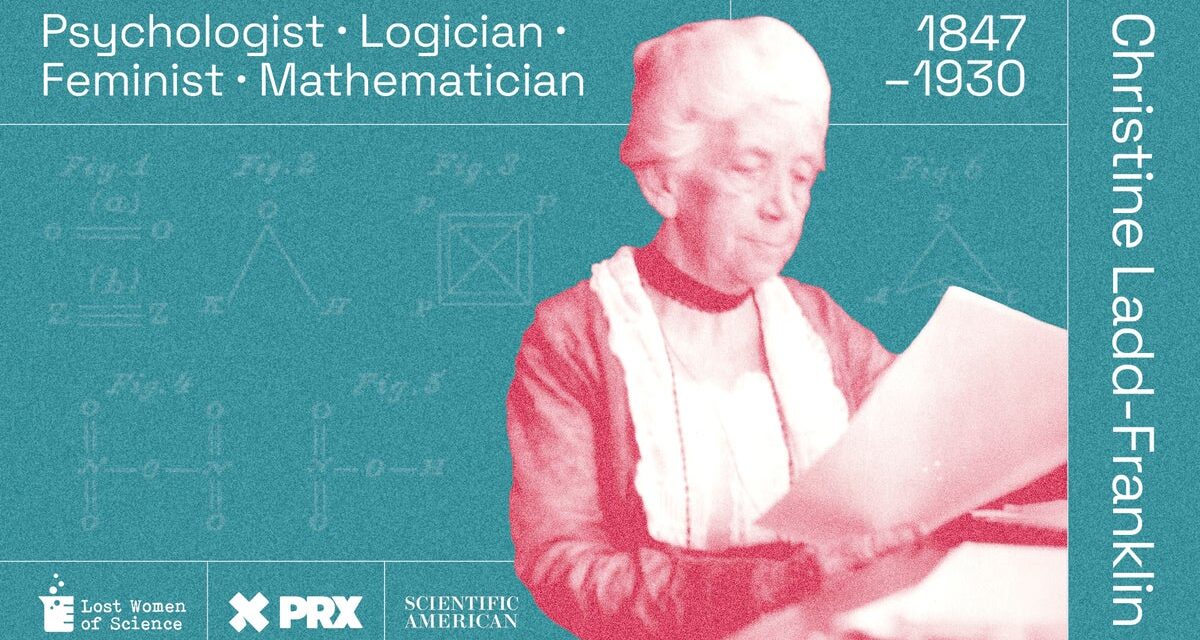

Polymath Christine Ladd-Franklin is best known for her theory of the evolution of color vision, but her research spanned mathematics, symbolic logic, philosophy, biology and psychology.

Born in Connecticut in 1847, she was clever and sharp-tongued, and she never shied away from a battle of wits. When she decided to go to college instead of pursuing a marriage, she convinced her skeptical grandmother by pointing to statistics: there was an excess of women in New England, so a husband would be hard to find; she’d better get an education instead. “Grandma succumbed,” Ladd-Franklin wrote in her diary.

When a man didn’t give her credit for her “antilogism,” the core construct in her system of deductive reasoning, she took him to task in print, taking time to praise the beauty of her own concepts. And when Johns Hopkins University attempted to give Ladd-Franklin an honorary Ph.D. in 1926, she insisted that the university grant her the one she’d already earned—after all, she’d completed her dissertation there, without official recognition, more than 40 years earlier. Johns Hopkins succumbed.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

[New to this season of Lost Women of Science? Listen to the most recent episodes on Mária Telkes, Flemmie Kittrell, Rebecca Lee Crumpler and Eunice Newton Foote.]

Lost Women of Science is produced for the ear. Where possible, we recommend listening to the audio for the most accurate representation of what was said.

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Katie Hafner: “I take it very ill of Mr. W.E. Johnson that he has robbed me, without acknowledgement, of my beautiful word ‘antilogism.’”

Carol Sutton Lewis: Oh, very well done, Katie!

Hafner: Yep, yep, that was me doing my best Christine Ladd-Franklin. Christine was a mathematician who specialized in symbolic logic. And in 1928, she was pissed off, or to put it more politely, put out, with this W.E. Johnson. And she published the note I just read in a journal called Mind to let him know.

See, Johnson had published a big, fancy series called Logic, meant to cover quote, the whole field of logic as ordinarily understood.

Sutton Lewis: Oh my goodness. Hmm. [laughs]

Hafner: I know, I know, not a lot of humility there. Okay, well, anyway, for the most part, Johnson’s work was very well received. But he made one critical mistake. He took credit for something called the antilogism, and that belonged to Christine Ladd-Franklin. The antilogism was her response to the syllogism, and I promise, we’re going to explain what all of this means later, but for now, what you need to know that Christine was pretty damn into it. She thought her antilogism thing was just fantastic. Throughout this note, Christine lavishly praises this original word of hers and the concept. The antilogism was quote “symmetrical”, “beautiful”, a more “natural form of reasoning.” She wasn’t about to let this Johnson fellow steal credit for it!

Sutton Lewis: Oh no, not at all. By this point in her career, Christine had had to fight to attend college, and fight to do a PhD in math at a university that didn’t admit women—a degree she didn’t even officially get when she graduated because they didn’t count her as a real student.

Meanwhile, William Johnson’s three volumes on logic made him famous. Thanks to that series, he got a membership in the British Academy and honorary degrees from more than one university. And he could have all that. But the antilogism? That was Christine Ladd-Franklin’s, and she wouldn’t give it up easily. And that diploma she’d been denied, she made sure she got that too.

This is Lost Women of Science. I’m Carol Sutton Lewis.

Hafner: And I’m Katie Hafner, and today, we bring you the story of Christine Ladd-Franklin.

Christine Ladd was born in 1847 in Windsor, Connecticut. Her parents both came from relatively wealthy families, and her mother, Augusta, was an early feminist. She used to bring little Christine to women’s rights lectures. Even though her mother died when Christine was just 12, and her dad sent her away to live with her grandmother, that sense that she could be just as intelligent, just as worthy as any man clearly stayed with Christine. And one thing she knew early on is that she wanted a proper education desperately.

Sutton Lewis: She was off to a promising start. At 15, her father sent her to Wesleyan Academy, a co-ed prep school in Massachusetts, where she was one of the top students in her class. And when she got word that a college for women would soon be opening nearby in Poughkeepsie, she could not contain herself.

And as you heard earlier, in this episode the voice of Christine is going to be our very own Katie. Right, Katie?

Hafner: Oh yeah, I’m going to channel my inner thespian, my frustrated actor.

Sutton Lewis: Your inner Christine. So take it away.

Hafner as Christine: I am crying for very joy. I have been reading an account of the Vassar Female College that is to be.

Sutton Lewis: 15-year-old Christine wrote in her diary

Hafner as Christine: The glorious emancipation proclamation for woman has gone forth and no power can put her back in her former state.

Sutton Lewis: And she goes on.

Hafner as Christine: Shall not woman, too, have the privilege of a university education is the question that millions are asking. Matthew Vassar, with his abundant dollars, with his practiced wisdom and his trained executive power, replies she shall!

Sutton Lewis: What an exciting time for women. You can just hear Christine’s enthusiasm for the fact that she’s going to get to attend college.

Hafner: Totally amazing.

Sutton Lewis: Yeah.

Hafner: And also, this was the time when all these women’s colleges were getting started because of all the men’s colleges that they weren’t allowed to attend.

Sutton Lewis: Mm-hmm. So Christine had a destination: Vassar. But convincing her family was another thing. Her grandmother was worried. What about marriage? Wouldn’t Christine be too old by the time she graduated? To convince her, Christine didn’t beg or throw a teenage tantrum. She used data.

Hafner as Christine: I assured her that it would afford me great pleasure to entangle a husband, but there was no one in the place who would have me or whom I would have.

Sutton Lewis: And then she threw in some statistics about-

Hafner as Christine: -the great excess of females in New England and proved that as I was decidedly not handsome, my chances were very small. Therefore since I could not find a husband to support me I must support myself and to do so I needed an education. Grandma succumbed.

Sutton Lewis: I j- just have to unpack that. She basically is telling her grandmother, I’m not pretty enough to depend on a man, so therefore I must depend on myself. And grandma went for it.

Hafner: True, true, true. And yet that was often a ploy. I’m sure Christine was just plenty attractive, but sh- it was often a ploy to say to your parents or your grandparents, oh gee, I’ll never get a husband. I’m just so unattractive. And then they, uh, surrender.

Sutton Lewis: Whatever it takes. So in 1866, Christine headed to Vassar with her family’s blessing. And when she first arrived, she was underwhelmed.

Hafner as Christine: With great sorrow I at once confess that I am grievously disappointed in Vassar. Instead of the independent university my imagination pictured, I find a fashionable boarding school. Instead of the tall intelligent and enthusiastic young women in blue merino that I fancied-

Hafner: Oh my god, tall! Why do they have to be tall? (Carol laughs) Okay, okay. I can’t be laughing.

Hafner as Christine: Instead of the call intelligent and enthusiastic young women in blue merino that I fancied, I find a troupe of young girls who wear black chamois and are wholly given up to the tyranny of fashion.

Sutton Lewis: So she is criticizing a group of women that don’t look like the women in her head, but the tyranny of fashion seems to be omnipresent, but in any event.

Hafner: Wait, wait, where is this diary? Does it still exist?

Sutton Lewis: Oh yes, this diary entry which slams Vassar is lovingly preserved in the Vassar archives.

Hafner: Really? Okay. Good for Vassar. So it wasn’t just the other students that disappointed Christine. At Vassar, Christine chafed at the rules. The women were subject to a strict schedule dictating their sleep, bathing times, and exercise. It felt so patronizing, not trusting women to set their own bedtimes. But she immersed herself in her studies, everything from Greek to geology, and she quickly progressed in science and math.

Frederique Janssen-Lauret: She wanted to do physics. She was really keen on physics.

Hafner: Frederique Janssen-Lauret is a lecturer in philosophy at the University of Manchester in England.

Janssen-Lauret: But physics you had to do in a laboratory. And they wouldn’t admit a woman to a laboratory. If people approved of women’s education at all, they often approved of them doing logic and pure mathematics because you could do that at home, and it didn’t require any worldly knowledge, which would sully women’s virtue, et cetera. It didn’t have any of that.

Hafner: So math and logic were more acceptable feminine pursuits.

Janssen-Lauret: Very interestingly now from our point of view, often even people who want to have more women in philosophy say that we should have less logic because women don’t like logic. I don’t really know what that’s based on, but it’s probably based on some sort of perception now that logic is masculine. And in those days, that was not how it was perceived.

Hafner: Who decided that logic was masculine? Anyway. So for the rest of her time at Vassar, Christine focused on math. She graduated in 1869 and it seemed like that might be the end of her academic career.

Sutton Lewis: But a few years after she graduated, an incredible opportunity presented itself. Or rather, as Christine would do throughout her career, she created an opportunity for herself.

In 1876, Johns Hopkins was established as the first American research university. It was open only to men. But Christine was determined. She contacted a math professor at this brand new university, James J. Sylvester, and she asked if he thought she might get in anyway. And he was actually enthusiastic.

You see, James was familiar with her work, and he had been discriminated against himself as a Jewish professor when he was seeking a position. There was still the issue of the Johns Hopkins no-women policy, but he managed to strike a compromise with the university. Christine would be allowed to study under him, but only unofficially. She’d get a stipend, and could attend his lectures, but she wouldn’t have an official title.

There was actually an article in the Chicago Daily Tribune about her going to Hopkins. But it wasn’t completely flattering. It said that Christine Ladd was clever “for a girl” and that one jealous mathematician suggested she was “a Ladd after all.”

Hafner: Oh, I just got that.

Sutton Lewis: [laughs] Yeah…

Hafner: Very funny. Still, she was in! And it was over the next few years as an unofficial graduate student in mathematics that Christine Ladd-Franklin came up with her beloved antilogism, the one that W.E. Johnson tried to take credit for.

Sutton Lewis: Okay, I’ve heard this word, antilogism. Why is the antilogism such a big deal?

Sara Uckelman: So the way to answer that question is to actually tell you what a syllogism is.

Hafner: Sara Uckelman, aka Doctor Logic, is an associate professor of logic at Durham University in England.

So if you didn’t take first year philosophy or if you don’t remember it, here’s an example of a syllogism.

Uckelman: All mammals are animals. All cats are mammals. Therefore, all cats are animals. The first two are the premises, the third one is the conclusion. The conclusion necessarily follows. If the first two are true, there is no way that the third one can’t be true.

Hafner: So this can all sound pretty academic, but syllogisms can help us think clearly, and avoid being led astray by the quirks of our minds. And thinking straight can get tricky. It’s so easy to get muddled when you hear something like-

Uckelman: All penguins are striped, all penguins can swim, therefore all striped things swim.

Hafner: I’m just having such PTSD because this is why I did so badly on my SATs. [Carol laughs] Just- but that’s okay, I’ll get through it.

What a good system of symbolic logic does is that let us get really organized. It makes sure our conclusions really follow from our premises, that our arguments are sound. And that matters in science, in politics, in everyday life. It just matters. Just imagine if everyone made logically sound arguments. I know, that’ll be the day.

But it turns out, Aristotle’s syllogisms were not the panacea for all our logic problems.

Uckelman: Now, Aristotle’s system was very constrained in that you had to have exactly two premises and a very limited sort of vocabulary. You could only talk about “all” and “some” and “none” and “not.” You could only talk about all and some and none and you couldn’t actually say things like “Socrates is a man” because it’s talking about an individual instead of just like some man, indefinite.

Hafner: I mean, so many rules! There are other kinds of arguments we might want to make.

Uckelman: So one of the questions that people were interested in generally in the 19th Century was, how do you give a general characterization of- you know, when you’ve got a bunch of sentences, which ones necessarily give rise to other conclusions, and which ones don’t.

Hafner: Aristotle’s approach was to go through each and every kind of syllogism and explain why it was logically sound or not. Which is fine if you don’t have too many. But once you get into all the different kinds of arguments, the possibilities are endless. You don’t want to go through them one by one. You want a more universal way to figure out which arguments hold up.

Uckelman: So the project that Christine Ladd Franklin was involved in is how do we give a general characterization of when you have a good argument and when you don’t.

Hafner: Enter the antilogism. Christine was considered a belligerent thinker by some, not necessarily in a bad way, but she did kind of have a habit of speaking her mind, vigorously arguing her points, or maybe, as someone once said about my mother, she might be called verbally pugilistic. And I feel like that really comes across in Christine’s antilogism.

So a simple example. As with the syllogism-

Uckelman: You take the two premises-

Hafner: All mammals are animals. All cats are mammals.

Uckelman: -and the negation of the conclusion

Hafner: Some cats are not mammals.

Uckelman: And you put them all together into one, and you say, you can’t have all of these at once.

Hafner: If a syllogism is a kind of friendly, positive “if A is true, then B must be true,” Christine’s antilogism is all about taking the negative of something, then showing how that makes everything incompatible.

And going negative turns out to be a really useful. The syllogism works only with two premises and a conclusion. But the antilogism-

Uckelman: -can generalize. So you could have, like, five sentences of which four can be true, but then the fifth one has to be false, and you can construct all the different arguments from that.

Hafner: And when Christine published her dissertation, peers in her field praised her contributions.

Janssen-Lauret: Someone called, um, Shen wrote a paper about this and said no scheme in logic is more beautiful than that put forward by Dr. Ladd-Franklin. If you look at A. N. Whitehead’s, his Universal Algebra, he talks about all this new work on quantification. And people now think, oh, he’s going to mention Frege. Nope. He mentions Ladd-Franklin. He goes, read this paper by Ladd-Franklin. It’s really good.

Hafner: Even John Venn – yes, that Venn, he of the Venn diagram – discussed her work in the Journal Mind.

Sutton Lewis: It sounds like Christine had more than earned that PhD in mathematics. And if she’d been awarded it back then in 1882, she would have become the first American woman to officially achieve that honor. But if you do a quick search for “first American woman to get a PhD in mathematics,” you get another name: Winifred Edgerton Merrill, who got her degree four years later in 1886.

And that’s because in 1882, the trustees of Johns Hopkins declined to grant Christine Ladd-Franklin a PhD for her work. Apparently getting a degree wasn’t part of the bargain they’d worked out for her woman-specific enrollment. Can you believe that?

Hafner: I can- Well, unfortunately yes, and you can’t see me shaking my head, but ugh.

Sutton Lewis: Just awful. But don’t worry. Christine’s going to take care of that in the most Christine Ladd-Franklin way. After the break.

Hafner: Christine Ladd was an intellectual force to be reckoned with. And during her time at Johns Hopkins, that very intellect caught the eye of one Fabian Franklin, a mathematics professor, who would become her husband. Fabian later recalled this one particular day where they spent hours debating logic on the steps of the Johns Hopkins building. Ah, so romantic!

Sutton Lewis: I know, so romantic. Really, just so cute.

Hafner: It was the spring of 1882. Christine and Fabian got married in August that year—a short courtship—and soon started a family. But Christine remained committed to her research. And fortunately, given the era, Fabian didn’t stand in her way.

Janssen-Lauret: Fabian Franklin, who was her colleague, he was a mathematician. He was very supportive of her academic career. So that was positive. If that hadn’t been the case, it would’ve been even more difficult.

Hafner: Over the next two years, Christine had two children, a son who died just a few days after childbirth, and a daughter, Margaret. The whole family went to Germany in 1891 for Fabian’s sabbatical, and as a new mother in the 1800s, you might expect Christine to slow down her career. But nope, she took the opportunity to throw herself into a whole new discipline: experimental psychology. We’re exactly not sure how she got into it, but she was a broadly curious person and it was a hot topic in Germany at the time.

Janssen-Lauret: She knew that some of the people in Germany would be happy to let a woman work in a laboratory as long as she wasn’t going to try to get a job in Germany, which they didn’t do for women.

Sutton Lewis: And in Berlin, she got to work with Hermann von Helmholtz, a pioneering physiological psychologist.

Janssen-Lauret: Helmholtz did quite a few things. He also did philosophy of science and also psychology, and he was doing research on color vision.

Sutton Lewis: At the time, there were two seemingly contradictory theories of color vision. Helmholtz’s theory was that our vision was trichromatic, based on three fundamental colors: red, green, and blue, which can be combined to make any other color.

The other theory said vision was tetrachromatic: red, yellow, green, blue. Christine said it was actually both, that in our eyeballs, we must have three color receptors, but at the level of sensation it feels like there are four building blocks.

But here’s her original contribution: she went on to explain how color vision would have evolved. It would have started as black-and-white, which is achromatic. Then it evolved into blue and yellow vision, and then finally into our red, blue, and green trichromatic vision.

Now, some of the details of her theory weren’t quite right. Like she thought most mammals have trichromatic vision, when most are actually dichromatic, but it was well-received at the time. And to the extent that Christine is remembered, it’s usually for her work on color vision, not so much the antilogism.

That’s probably because Christine promoted the hell out of her color vision theory. She spent the next 40 years of her life publishing about it herself, getting others to write about it, teaching courses, really doing everything she could to spread the word, and to ensure that people knew it was her theory. But by the way, she wasn’t only concerned with credit for herself.

Janssen-Lauret: Franklin also wrote articles to recover works by other women. She wrote these papers on what other women had contributed to the field. I haven’t seen anyone else in this period who worked on logic also doing that. And I thought it was really nice to see that this is also something that she did

Hafner: But you’ve still probably never heard of Christine Ladd-Franklin. So why isn’t she remembered?

Janssen-Lauret: Usually I say to this, my short answer is sexism and long answer is sexism, sexism, and sexism.

Hafner: And maybe sexism. Frederique Janssen-Lauret and her colleague Sophia Connell have written about a “feedback loop of exclusion” that keeps women out of the philosophical canon. They aren’t cited as much in their time, so they aren’t cited as much by subsequent historians. Many of Christine Ladd-Franklin’s contemporaries are the men you’ll learn about in an introduction to philosophy class. Even if their views were later superseded, they serve as a foundation. Their theories are seen as worthy of reading for their own sake.

Christine wasn’t always included then, so she’s mostly not included now. Of course, as we’ve heard, she fought for recognition every step of the way.

Janssen-Lauret: With Ladd-Franklin in particular, we see her saying, um, actually, I had that idea first, and this person hasn’t credited me, and they should.

Hafner: Unfortunately W.E. Johnson’s theft of her quote beautiful word wasn’t the only offense.

Janssen-Lauret: In color vision, she did the same. She was always picking people up saying, you’re not engaging with my work, but actually I had this idea first. And some of the reviewers say that that’s aggressive, et cetera.

Hafner: Can I just point out how frickin’ sexist that is?

Sutton Lewis: Yeah.

Hafner: This is just really making me chafe.

Sutton Lewis: You stick up for yourself and that’s called being aggressive.

And then there’s just one more example I wanted to share of Christine taking her male peers to task. Because she does-

Hafner: Please do.

Sutton Lewis: Absolutely. Because she does not hold back here. Let me tell you what happened. So Christine had a decades-long correspondence with the Cornell psychologist E. B. Titchener. Titchener had a vision of creating what he called an “experimental club” with men moving around in the lab, smoking, engaging in frank discussion, and of course, no women allowed.

Christine wasn’t about to let that slide. She wanted to present her work in experimental psychology to the club, and the affront was particularly great when the club planned to meet at Columbia University in New York City in 1914 at the time that Christine was teaching there, albeit with no official title or salary. So she wrote to Titchener-

Hafner as Christine: Is this then a good time, my dear Professor Titchener, for you to hold the medieval attitude of not admitting me to your coming psychological conference in New York at my very door? So unconscientious, so immoral – worse than that – so unscientific!

Sutton Lewis: You tell him, Christine. Titchener, for his part, wrote frantically to another male psychologist before the meeting: “I have been pestered by abuse by Mrs. Ladd-Franklin for not having women at the meetings, and she threatens to make various scenes in person and in print. Possibly she will succeed in breaking us up, and forcing us to meet–like rabbits–in some dark place underground.”

Note that he doesn’t suggest that they think about changing their rule, but- but is more concerned about how you have to go underground.

Hafner: But- and let’s just complain man to man about what should happen happen to these women who are suggesting that we become rabbits.

Sutton Lewis: [laughs]

Hafner: But there was one important battle Christine did win. In 1926, Johns Hopkins University held celebrations for its 50th anniversary. It offered to grant Christine Ladd-Franklin, then age 78, an honorary degree.

But that would not do. Christine reminded them that she had never received the doctorate she earned back in 1882 – and she believed she should be given that one rather than an honorary one i.e. a fake one. Johns Hopkins agreed. And so, 44 years after she had completed the requirements, she was finally granted a PhD for her work in symbolic logic. She died four years later.

Sutton Lewis: Throughout her life, Christine kept churning out ideas, whether she got credit for them or not. Our producer Ann Tyler Moses dug up this old diary entry where Christine was charmingly aware of her own insatiable curiosity.

Hafner as Christine: The bright girl is thinking of going to Europe this summer. Now the bright girl is nothing if she is not full of original ideas, and hence it may easily be guessed that she has got an original idea in regard to seasickness.

Sutton Lewis: She went on to write about the connection between motion sickness and the inner ear – an idea that was quite new in the late 19th Century. And we don’t need to get into all of that now, but one point is inarguable. That bright girl really was nothing if not full of original ideas.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Christine left us plenty of material to remember her by. And so before we end this episode, we just have to tell you about some of this because it is just so good. Throughout her life, on top of all her academic writing and diary writing, Christine published countless essays and letters to editors.

Hafner: Oh no, my dad and my father-in-law used to do that all the time, and it was so embarrassing.

Sutton Lewis: Hm, but impressive because they got published. And our producer, Ann Tyler Moses, dug deep into the archives and pulled out some gems. Ann Tyler, would you tell us about some of the ones you found?

Ann Tyler Moses: Yes, so I was looking through her published letters at the Columbia Library and found passionate essays on the importance of ventilation, “the crime of accepting tips,” the importance of dehydrating vegetables during the war (Katie laughs), hygiene in the army, proper desks-

Hafner: What? Hygiene in the Army?

Tyler Moses: -proper desks for students-

Sutton Lewis: Okay, she was never at a loss for something to say. The crime of accepting tips. I love that one.

Tyler Moses: Oh.

Hafner: Oh there’s more?

Tyler Moses: Yeah, she wrote frequently about the artificial language Esperanto and her preferred alternative, Ido. Because Esperanto she found sexist, since for the word “mother” it used something like “female father.”

Sutton Lewis: And of course, in typical fashion, she would find an alternative.

Hafner: Go on.

Tyler Moses: Yeah, she wrote to multiple newspapers urging the adoption of the name “Usonians” for what we now call “Americans.”

Hafner: Is that like US-onians?

Tyler Moses: Like, yeah, US of- well, United States of North American. USONA is where that comes from.

Um, as she said, “So long as we are inside our own country we may be able to throw logic to the winds and think of ourselves as Americans. But for our men who are ready to fight side by side with the Canadians and South Americans, it is a little absurd for us to gobble up the name American.”

Sutton Lewis: You know, she has a point there.

Hafner: She always did, didn’t she.

Sutton Lewis: This episode of Lost Women of Science was hosted by me, Carol Sutton, Lewis.

Hafner: And me, Katie Hafner. It was produced by Anne Tyler Moses with our senior producer Elah Feder. We had fact checking help from Lexie Atiya. Lizzie Younan composed all our music. We had sound design from Hans Hsu and Alvaro Morello, who also mastered this episode.

Sutton Lewis: We want to thank Jeff DelViscio and our publishing partner, Scientific American. We also want to thank Lost Women of Science co-executive producer, Amy Scharf, and our senior managing producer, Debra Unger. Special thanks also to Paloma Perez-Ilzarbe who spoke with Ann Tyler for this episode.

Hafner: Lost Women of Science is funded in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and Schmidt Futures. We’re distributed by PRX. You can find transcripts of all our episodes on our website, lost women of science dot org, as well as some further reading. If you wanna learn more about Christine Ladd Franklin’s work, go to the website. And don’t forget to hit, Carol, what is it we want everyone to hit? The-

Hafner and Sutton Lewis together: donate button!

Hafner: Again, it’s lostwomenofscience.org

Sutton Lewis: See you next week.