The 2023 Windy City Smokeout was housed in the parking lot of the United Center, on Chicago’s Near West Side. It’s a massive stadium space built in 1994, an “urban renewal” project that has yet to see full gains for those who lived in the community. It’s best known as the home of the Chicago Bulls, but this summer will have seen concerts from Chance the Rapper, Earth, Wind & Fire, and Arctic Monkeys. I previously attended Stevie Wonder’s “Songs in the Key of Life” tour there, where Stevie was able to create a sense of intimacy despite the 23,000 people in attendance, leading us in a collective “Isn’t She Lovely” that still gives me chills to remember, the song and the space very much alive. But for many activists, the stadium has been a community death knell, a sign that Chicago is becoming too expensive for its poorest residents, especially residents of color.

As my partner Annie and I made our way from one of the stadium’s many nearby parking lots toward the Smokeout—a country music, craft beer, and BBQ fest celebrating its tenth anniversary this year—there was the eerie feeling of walking through a neighborhood that’s been gutted. I could hear cars and the occasional truck from the nearby Eisenhower Expressway, which, after it was constructed in the mid-twentieth century, became an important route from Chicago’s downtown to the suburbs, enabling white flight. I could see new-looking storage units and office buildings, but few homes, restaurants, or grocery stores. Police cars blocked traffic to allow the festival attendees, many of whom were wearing cowboy boots, to walk freely through the streets. The t-shirts we saw claimed their loyalties: Taylor Swift, Jim Beam, Coors, We are Penn State, Breland, New York Yankees, The Chicago Police, And Brisket For All. We saw snakeskin, leopard skin, florals, gingham, and so many cowboy hats, of course—in blue and black and brown and Barbie pink, and one with a wedding veil attached. The crowd moved in pairs and small groups, melding as they approached the entrance like iron fillings drawn by a magnet. As we got closer, we could feel the vibrations from music on the bottoms of our feet.

This was a young, mostly white crowd, and we stood out: a middle-aged Black and white lesbian couple in sensible sandals. But we did see a sprinkling of other Black, Latinx, and Asian folks— it seemed like more than when I had attended the festival in previous years. When we passed one of the last public housing units left standing in the neighborhood, a group of Black teenagers were making snow cones to sell to the crowd. A young Black woman in short locks zipped past us in the opposite direction, maneuvering a Lime electric scooter against the force of the crowd. “Excuse me!” she said, bright and determined, her destination elsewhere.

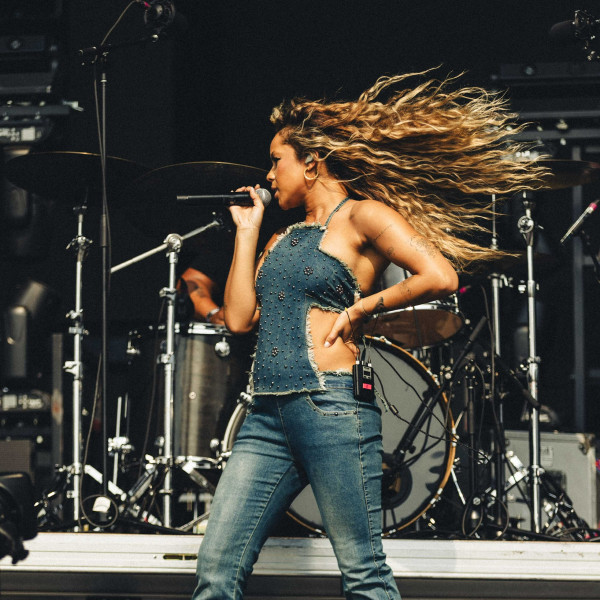

We came to the Windy City Smokeout specifically to see the Black country artists Darius Rucker and Tanner Adell, a pair of musicians at very different points in their careers. Rucker is at work on his eighth studio album and has had nine number one singles on the Country Airplay chart. He is probably one of the most visible Black country music artists who enjoy mainstream radio play today, a very small group that also includes Rissi Palmer, Mickey Guyton, Kane Brown, and Jimmie Allen. Tanner Adell, on the other hand, is an up-and-comer with a growing presence in the Nashville club scene, on streaming platforms, and on social media. Her song “Honky Tonk Heartbreak” soundtracked a 2022 performance by the Dallas Cowboy Cheerleaders, and she recorded a duet called “Cheddar Biscuits” with the Louisiana-born country and hip-hop genre-crosser Willie Jones. At the time of this writing, her growing fan base includes over 450,000 followers on TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter; if she isn’t yet a household name, that should soon change. She is signed to Columbia Records, and her eight-track debut mixtape was released on July 21, 2023.

In a review for Billboard, Jessica Nicholson described the tape’s title track, “Buckle Bunny,” as a song “vibrating with confidence,” praising Adell’s blending of country iconography and hip-hop swagger. The feisty, boot-stomping “Throw It Back” offers an unapologetically sex-positive message about love and relationships; “Just ’cause he’s got them big brown eyes / Don’t mean that he can see,” Adell advises her listeners. Her slower songs cut through the sugar offered by some country ballads to present a saltier, down-to-earth vision of romance. On “Love You a Little Bit”—her most popular song on Spotify, with more than twenty-eight million streams—she offers a moment of quiet, as she realizes she’s falling in love on an everyday Tuesday car ride: “Wasn’t nothin’ special, just the same old same / No love songs on the radio playin’ / You were just drivin’ and holding my hand.”

The fact that the festival featured both Adell and Rucker may be a sign of a changing country scene, where musicians, journalists, scholars, and activists are pushing the industry to be accountable for its exclusionary history. Like other country music spaces, the Windy City Smokeout has undoubtedly been shaped by the segregated history of how the genre has been created and marketed, with its bifurcation of “Hillbilly music” (which later became country music) marketed to white audiences and “race music” (which included blues, rhythm and blues, and jazz) marketed to Black listeners. And of course, Chicago’s country music spaces are shaped by the continued class and racial segregation here, where this “city of neighborhoods” has boundaries that are sometimes unspoken, and sometimes violently felt when you wander into a community that is not your own.

To test the comfort level and feeling of community among Black and other people of color at the festival, I decided on the not very scientific strategy of “the nod,” or what Black poet and essayist Ross Gay calls “negreeting”—a nonverbal form of acknowledgement and connection between Black people in public spaces, however brief. But I was having trouble getting a response to my negreetings. Maybe I was being a little needy, a little too hungry for a response from these strangers. Or maybe the other people of color at the festival didn’t want to acknowledge our shared state of outsiderhood, especially as they kicked back with their white friends and loved ones. Or maybe “negreeting” is just too old-fashioned, a form of connection from an earlier era when our precarity in white spaces was forced to be expressed in code. After about six tries, I finally got a nod from a young Black man in locks, full beard, and a Chance the Rapper t-shirt. He smiled widely at me, and even removed his sunglasses. Time slowed, and for a moment, I felt a little more at home.