In 1920, W. E. B. Du Bois published Darkwater: Voices From Within the Veil, a collection of essays, spirituals, and poems that channel his anger toward what he calls the “great, red monster of cruel oppression.” Tucked within was one of Du Bois’s more atypical works, a short science-fiction story called “The Comet.” It follows Jim, a Black man in New York City who one day finds that a comet emitting deadly gas has passed by, killing almost everyone. The only other survivor Jim encounters is a rich white woman named Julia, and for a while, they take solace in each other’s company—until Du Bois reveals that this dystopia hasn’t annihilated racism.

“The Comet” is one of the earliest examples of Black artists using science fiction, fantasy, and horror to dramatize the terrors of racism, to subvert genre conventions, or simply to tell frightening, fantastical tales. A significant history of Black writers employing those elements has developed in the years since: Consider Beloved, Toni Morrison’s 1987 Gothic masterpiece about a formerly enslaved mother who believes that she’s haunted by the ghost of her murdered child. Or look to Nalo Hopkinson’s prescient 1998 dystopian novel, Brown Girl in the Ring, in which a walled-off inner city suffers when affluent residents flee to the suburbs. Horror is a powerful tool, academics such as Robin R. Means Coleman have argued, because Black artists can take basic themes from the genre—looming violence, loss of control, and fear of the Other, for example—and employ them to reflect truths of Black life.

Some of the books below are situated squarely in the past. Others imagine bleak futures or deal with turmoil in contemporary life. In each, the fearsome elements are both riveting and instructive. Here’s hoping they keep you up at night.

The Reformatory, by Tananarive Due

Robbie, the 12-year-old protagonist of The Reformatory, isn’t a reckless kid. But his impulsive decision to defend his sister from a leering older boy—the son of their town’s wealthiest landowner—gets him in serious trouble. The novel follows Robbie to the Gracetown School for Boys, a segregated reform school in 1950s Florida, where his ability to see ghosts is no longer just a comforting way to keep his deceased mother close—and is no longer unique. At Gracetown, Robbie experiences terrors both mundane and supernatural. “In summer, sometimes babies died in their sleep, petrified by ghosts,” Due writes. But the children are left to suffer on their own, disbelieved by adults—even ones who have observed similar phenomena themselves. The atrocities in The Reformatory are particularly harrowing because they might have been avoided if anyone had just listened. Due, who teaches a course on Black horror and Afrofuturism at UCLA, is both a scholar of the genre and a prolific writer of it: She also has a story in Out There Screaming: An Anthology of New Black Horror, edited by the Get Out director Jordan Peele and the science-fiction veteran John Joseph Adams, and published this month.

The Black Guy Dies First, by Robin R. Means Coleman and Mark H. Harris

This comprehensive look at the film industry tries to illuminate why “Black horror is currently having a yearslong ‘moment.’” It builds on Coleman’s earlier book, Horror Noire, and includes analysis of Peele’s films and several others from the past decade, along with earlier productions such as ‘70s blaxploitation movies. The book pairs that exploration with humorous musings on cinematic racism and accessible investigation of familiar tropes—including the one for which the book is named, a sardonic crystallization of how Black people have been treated in the genre. The authors conclude that “Black horror’s triumph is its ability to reflect more deeply on the ways in which Black history has been and continues to be Black horror.” Come for the historical insights, stay for the “Frequent Dier Awards,” given out to actors whose characters most often … well, you know.

The Gilda Stories, by Jewelle Gomez

More than 30 years after its release, The Gilda Stories remains a remarkable novel. The book begins in 1850s Louisiana, where an unnamed girl who has just escaped enslavement is hiding in a farmhouse root cellar. Trembling and covered in blood, she’s awakened from her fitful sleep by a Black woman named Gilda, who owns a nearby brothel with her partner, a Native American woman named Bird. Gilda and Bird also happen to be vampires. Gomez’s vampires are telepathic, which gives the characters opportunities to communicate with one another on frustrating, layered, delicious levels, and allows the book to shift deftly between multiple perspectives. And despite her initial fear upon discovering that Gilda can hear her thoughts, the girl grows to see the two women as her family, deciding to become a vampire herself and taking on Gilda’s name when the older woman chooses to die. The Gilda Stories tackles weighty subjects such as slavery and sexual assault, but doesn’t relish violence for violence’s sake. Instead, the book, which was born of Gomez’s desire to see “a lesbian of color embark on the adventure of eternal life,” is full of curiosity and compassion—a particular pleasure in a story about queer monsters.

Bloodchild and Other Stories, by Octavia E. Butler

There’s no wrong place to start if you’re looking to explore Butler’s oeuvre for the first time—and if you’ve recently read The Gilda Stories, the natural transition point might be Fledgling, Butler’s profoundly empathetic 2005 vampire novel. But Bloodchild and Other Stories, Butler’s collection of essays and science fiction, offers a revelatory look at the author’s creative process. In the preface, Butler writes that “what people bring to my work is at least as important to them as what I put into it,” but she nonetheless presents a road map for understanding her writing: She follows each piece, including the disturbing titular tale, with an afterword. Taken together, her notes constitute a manual for readers, a series of interludes that feel intimate yet instructional. And then, of course, there are the stories themselves: “Bloodchild” is a parable of human and alien symbiosis packed with scenes as squeam-inducing as an emergency C-section performed on a pregnant human host who’s being eaten alive by his hatching, insectlike larvae. Like much of Butler’s work, it’s not for the faint of heart.

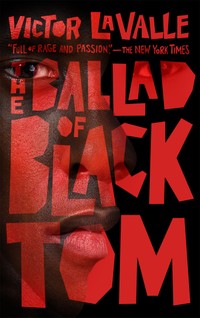

The Ballad of Black Tom, by Victor LaValle

LaValle’s 2016 novella revisits H. P. Lovecraft’s 1925 short story “The Horror at Red Hook.” Like much of Lovecraft’s work, it is oozing with racist contempt—it portrays a Brooklyn populated by “swarthy, sin-pitted faces.” LaValle’s update is both daring in its formal choices and thrilling in its narrative ones. His story focuses on Tommy Tester, a young Harlem hustler hired to deliver a mysterious book to a sorceress in Queens. After entering her world, Tommy encounters two characters borrowed from Lovecraft, the rich occultist Robert Suydam and the detective Thomas F. Malone. The novella eventually veers into classically monstrous territory, but LaValle conveys a creeping sense of dread well before introducing paranormal figures. Take this description of Tommy’s uptown life: “Walking through Harlem first thing in the morning was like being a single drop of blood inside an enormous body that was waking up.” It reminds me of something LaValle told The Atlantic a year after Black Tom’s release. “This is the kind of horror that’s best, and most lasting,” he said. “The kind that speaks to a deeper emotional truth. It’s not simply about a monster, and what that monster looks like, it’s what the monster means.”

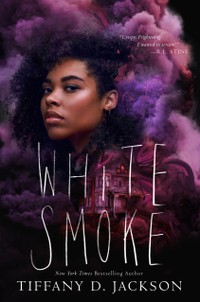

White Smoke, by Tiffany D. Jackson

Jackson’s modern take on the haunted house introduces a teenage girl named Marigold, who’s been displaying symptoms of “delusional parasitosis”—she’s seeing insects that aren’t there—after suffering a bedbug infestation in her childhood home. This quotidian nightmare immediately puts the reader on edge: Marigold is a girl possessed, convulsing in one scene as she remembers that “female bedbugs may lay hundreds of eggs, each about the size of a speck of dust, over a lifetime.” And that’s all before the ghosts come out to play. When Marigold’s mom moves them to a new home halfway across the country, the teenager has to share a room with her 10-year-old stepsister, Piper—and Piper’s imaginary friend, who wants Marigold gone at any cost. White Smoke pairs classic horror conceits with depictions of adolescent angst that feel just as terrifying. The Goosebumps-inspired thriller pulls in sharp critiques of gentrification and other social inequalities through the eyes of its young protagonist, and although it’s marketed as YA, it will remind readers of all ages that teens are far more perceptive than adults tend to give them credit for.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.