In Roman Africa, during the last years of Emperor Constantine the Great’s long reign, a slave spoke up to criticize her master’s daughter. The speaker was not the kind of person who is normally noticed by history, since she had neither wealth, nor power, nor legendary beauty. We know very little about her, only that she was a child. We do not know whether she survived to adulthood. She may have been one of the many Roman children who did not live to see their tenth birthday. This was common in the Roman world, especially, but not only, among slaves and the poor. In the normal way of things, Illa would have been one of the forgotten people of history. But another child noticed her defiant act of truth telling and grew up to speak of what she learned from her. We do not know what she was called. The one source that remembers her does so only as ancilla—the Latin for a handmaid or female slave—or illa, which simply means “she.” We will meet her more than once in what follows, and we will speak of her as “Illa,” letting the unfamiliar Latin form become something like a name.

In the Roman world, people living in slavery did not have legal names. They had informal nicknames, used perhaps by the people who cared for them as children or by those who exploited them when they were old enough to work. A slave’s nickname might change with his or her circumstances. A handmaid might be addressed simply as puella (“girl”) in the same demeaning way that men of color in the Jim Crow South were called “boy.” A name was a sign of standing, something a slave did not have. But if Illa had no standing, she had a voice. And, perhaps remarkably, she was not afraid to let herself be heard.

The people in Augustine’s life—the women in his life—had a profound impact on the lives of Christians for centuries to come.

Illa would sometimes run errands with the master’s free daughter, and in later life the young mistress remembered her as a fierce little person. From Illa she learned a lesson she would carry with her all her life: that sometimes God’s voice speaks through unexpected people. A person’s earthly standing does not determine the value of what she or he has to say. As the daughter of a provincial landowner of modest fortune, the young mistress was also a person who did not expect to be remembered in the historical record. But in the way of things, she grew up to become a mother, and one of her children grew up to become the most influential thinker of Latin Christianity: St. Augustine, bishop of Hippo.

The young mistress would find a place in history as St. Monnica, one of the heroines of the early church. Illa and Monnica grew up together in Roman Numidia, probably in the Tell, the countryside of fertile valleys just south of the coast, in what is now the northeastern corner of Algeria. It was a vast agricultural landscape dotted with rural estates and small communities that, even if they had municipal status, only counted a few thousand souls among their inhabitants. It was not the kind of place where one expected history to be made. Yet long after she left Africa, Monnica told stories of her childhood to her children and grandchildren, and through her son Augustine, her stories passed into the historical record. They became part of the teachings of Christianity, along with the morals she drew from them. Monnica’s childhood companion could not have known that the story of how she challenged her little mistress would be told again and again, across the centuries, to illustrate the idea that we live in a fallen world where the people in power are not always right. This simple insight was central to Augustine’s mature thought, and it is in many ways Illa’s legacy.

Illa, Monnica, and the other women in our narrative lived and died well over a thousand years ago, and it is surprising how well we know some of them given the passage of time. They were remarkable women. But in the ancient world, remarkable women routinely lived and died without leaving a trace. Only a very few received more than a line or two in the historical sources—one thinks of Mary, mother of Jesus; of Livia, wife of the emperor Augustus; or perhaps of Cleopatra, who was queen of Egypt in her own right. In each case they are remembered for their role in the supporting cast around an important man.

Rarely does a source record the woman’s inner thoughts. But with Monnica of Thagaste, this changes. Alone among the women of the ancient Mediterranean world, Monnica raised a son who not only noticed women but explored in depth what he learned from them and broadcast what he learned to the wider world. Monnica’s son Augustine, it has long been acknowledged, was the first ancient writer to produce an autobiography. His Confessions tells the story of his early life and the people he knew, and in them he tries to make sense of his thoughts and experiences. In reflecting on his life, he explored wider ideas about the relationship between men and women, forged by years of listening to and even arguing with the women in his life. Other men had experimented with sharing their private thoughts. Marcus Aurelius had composed his Meditations more than two centuries earlier. But Augustine had the instincts of a novelist. He was interested in how the seemingly insignificant facts of daily life, and the seemingly insignificant people in a household—the women and children—contributed to the process in which his character and destiny had taken shape.

Augustine was a man who noticed women. Among the influential figures he captures in his narrative, his mother, Monnica, stands out. He returns again and again to her actions, to the stories she told, to the emotions that colored her life. Historians have long recognized her profound influence on her son, but they have paid less attention to what his writings can tell us about Monnica herself. If we listen closely, in her son’s words we can sometimes hear Monnica’s voice. Augustine had been living in an all-male monastic community for some time when he wrote his Confessions, so the fact that his reflections on his past are so rich with female characters comes as something of a surprise. As he remembers them, the women he writes about are bright and sharp—even spiteful at times. They are people who have agendas of their own. Not all of them are people he knew personally or cared for, but always, without exception, he shares details about them that we would not otherwise know. In all but two cases, the women of the Confessions are figures who would otherwise be lost to history. The two exceptions are the Roman empress Justina and Monnica, Augustine’s own mother. In Monnica’s case the only other marker of her life that remains is the epitaph inscribed on her tomb—the wide canvas of her life distilled into brief lines about how a virtuous mother is made fortunate by her offspring. Because he is our only source, the women in this book are in some sense Augustine’s women: they are characters in his narrative. We have no way of knowing what they were like aside from what he tells us, what uncomfortable facts he may have buried, or what he may have missed. As grateful as we may be for what he tells us about them in his Confessions, they are not the primary focus of the story he is trying to tell, and one can only imagine how the women themselves would have told their own stories. Augustine looms large, and seeing past him requires effort. His own thoughts and feelings keep intruding into the story in a way that is both revealing and distracting. So if we want to be able to imagine what it was like for these women to be alive, we have to be resourceful in reading between the lines.

____________________________________

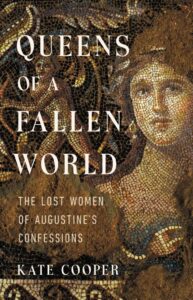

Queens of a Fallen World: The Lost Women of Augustine’s Confessions by Kate Cooper has been shortlisted for the 2023 Cundill History Prize.

____________________________________

Augustine and his women lived at a turning point in history, the closing decades of the Roman Empire. The whole Mediterranean was still under Roman rule in those days, and it had long been taken for granted that Rome’s power reached to the end of the known world, from the Western Ocean to the desert of the East. But that was changing. Pressure on the northeastern frontier had been building; in Augustine’s lifetime barbarian warlords would begin to chisel away whole regions, refashioning them as autonomous kingdoms. Within living memory, a religious revolution had taken place: in the time of Augustine’s grandparents, the emperor Constantine had prayed to the God of the Christians before a battle and pledged himself to their God when his armies proved victorious. It is almost impossible to capture the sense of uncertainty experienced by Roman citizens as the empire was beginning its long decline and by Christians in the brave new world where Christians were no longer a persecuted minority. The possibilities were endless, and the stakes were high. Augustine’s long life spanned from the reign of Constantine’s son Constantius (AD 337–362) to the barbarian invasions of the first decades of the fifth century. His mature adulthood fell during the years when the groundwork for the social and cultural world of medieval Latin Christendom was being laid—and as things turned out, he would play a significant part in laying this groundwork. The beliefs he came to hold about love and marriage, about human disappointment and human hope, would have a far-reaching influence on how medieval people saw the world. So, whether they knew it or not, the people in Augustine’s life—the women in his life—had a profound impact on the lives of Christians for centuries to come.

The story Augustine tells of the women in his life offers a glimpse of their struggle to maintain their dignity.

One of the central tenets of Augustine’s mature thought is that as human beings, we can never know the consequences of our actions ahead of time; only God can know the future. We humans are trapped in time, and this compromises us morally: unintended consequences are the stuff of human experience. We have no way of knowing how our actions will intersect with unfolding events or the actions of other human beings, so we can never adequately judge the possible effects of our actions or be sure what is the right thing to do. This was particularly true where relationships between men and women were concerned. Augustine might have appreciated the irony that one of the things that made the world unpredictable for Roman men was the immense energy Roman women put into seeming biddable. Roman women were full of surprises: as children, they learned to erase the traces of their own efforts wherever possible, even as they passionately pursued their own agendas and goals. This led Roman men to find them baffling. It also makes them worth watching, from a modern historian’s perspective: sometimes keeping an eye out for what women were doing behind the scenes can shed a surprising light on the course of events. Despite his own status as a privileged male, Augustine’s writings open a window onto the lives of women from all walks of life. He writes about ordinary housewives, about women living in slavery, and even at times about the women of the imperial family. Often, he gives us surprising and unexpected glimpses into the challenges women faced and the space they were sometimes able to carve out for themselves. The story Augustine tells of the women in his life offers a glimpse of their struggle to maintain their dignity in difficult circumstances and to leave a trace of their lives. We are used to thinking of the women of the past as silent, since few sources have survived to preserve their voices. But Augustine is not a writer who expects women to be silent. He often found them memorable precisely for what they said. He recalls, for example, his concubine’s desperate vow when he ended their relationship and sent her away. Equally unforgettable are his mother’s prayers, her cajoling, and her conversations with bishops in her quest for advice on how to shape her errant son into a good Christian. Even the slaves and children in the house where Monnica grew up played a part: one thinks of the elderly nurse who took care of Monnica when she was a child and of Illa, the playmate who challenged her and changed the way she thought about herself. It should not be surprising, then, that in the Confessions enslaved women consistently come across as honest and reliable people capable of speaking truth to power. Augustine was fascinated by the idea that God distributes the ability to do good in the world evenhandedly and that human beings are just as likely to hear his voice speaking through women, slaves, and children as through powerful men.

__________________________

From Queens of a Fallen World: The Lost Women of Augustine’s Confessions by Kate Cooper. Copyright © 2023. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.