November 15, 2023

3 min read

Key takeaways:

- Conditions more likely in Indigenous coal miners included black lung and respiratory impairment.

- By not using Indigenous-specific spirometry standards, some disabled Indigenous miners may not be compensated.

Older Indigenous coal miners faced a higher likelihood for black lung disease and respiratory impairment than non-Indigenous miners, according to study results published in Annals of the American Thoracic Society.

Jeremy T. Hua

“We know that Indigenous (American Indian/Alaska Native) groups face numerous health disparities (such as access to medical screening and early diagnosis) compared to other populations, but we were still surprised to find that older Indigenous coal miners — despite less frequent smoking — were more likely to develop abnormal lung function and black lung than non-Indigenous coal miners,” Jeremy T. Hua, MD, MPH, pulmonologist in the division of environmental and occupational health sciences at National Jewish Health and assistant professor at the University of Colorado, told Healio.

Using 2002 to 2023 medical surveillance data from National Jewish Health, Hua and colleagues assessed 691 Western U.S. coal miners who worked for at least 1 year to determine how the likelihood for pneumoconiosis/black lung and respiratory impairment differed between Indigenous individuals (n = 289; 7% women) and non-Indigenous individuals (n = 402; 96% white/Hispanic; 3% women).

Smoking appeared less prevalent among Indigenous miners, with a higher percentage of these miners vs. non-Indigenous miners reporting being never-smokers (90% vs. 48%; P < .001). Further, among those who did report current or past smoking, researchers found fewer total smoking pack-years in the Indigenous miner population (mean, 7.4 vs. 22.8; P < .001).

Total mining tenure was 29.4 years among Indigenous miners, whereas this total time was shorter in non-Indigenous miners (22.7 years; P < .001). Indigenous miners also spent more time surface mining (28.6 years vs. 8.7 years; P < .001).

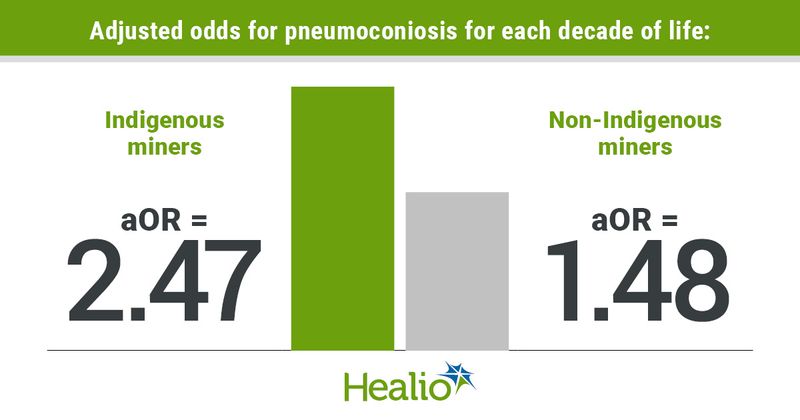

During multivariable analysis that accounted for sex, smoking pack-years, total mining tenure and primary surface/underground mining, both groups of coal miners had heightened odds for pneumoconiosis, but the likelihood was higher in the Indigenous group with each additional 10 years of life (adjusted OR = 2.47; 95% CI, 1.66-3.68) vs. in the non-Indigenous group (aOR = 1.48; 95% CI, 1.19-1.85).

A similar pattern occurred when researchers evaluated the likelihood for respiratory impairment, with increased odds for this outcome among Indigenous miners (aOR = 1.67; 95% CI, 1.25-2.24) vs. non-Indigenous miners (aOR = 1.06; 95% CI, 0.9-1.25) for each decade.

Notably, Indigenous miners had lower predicted probabilities for both outcomes earlier in life and higher predicted probabilities later in life (pneumoconiosis, age 65 years; respiratory impairment, age 75 years) compared with non-Indigenous miners, according to researchers.

A larger decline in FEV1 for each 10 years of life was also found in Indigenous vs. non-Indigenous workers (0.397 L vs. 0.326 L).

In the cohort of Indigenous miners, researchers also compared lung function standards as they related to the U.S. Department of Labor criteria for federal black lung disability compensation to see how the number of qualifying individuals differed based on the standard.

Researchers found that 18 Indigenous miners qualified using an Indigenous-specific spirometry standard (Marion), but six (33%) no longer met the disability criteria when using the U.S. Department of Labor-mandated standard (Knudson).

Further, among the Indigenous miners who qualified for compensation using the Marion standards, five would no longer qualify with use of the GLI-Global standards, and three would no longer qualify with use of the NHANES III-Caucasian standards.

“Future studies should focus on the reasons why Indigenous coal miners are more likely to develop abnormal lung function and black lung — for example, whether there are differences in workplace dust exposure conditions or other factors that may be contributing to poorer lung health,” Hua told Healio.

“This study helps shed light on health disparities for Indigenous miners, a group that has not been well-studied,” Hua added. “The findings from this study should inform additional research and policy changes to recognize and prevent chronic lung disease, especially in underserved populations.”

Reference:

Sources/Disclosures

Collapse

Disclosures:

Hua reports no relevant financial disclosures. Please see the study for all other authors’ relevant financial disclosures.