WASHINGTON — In the next few weeks college students will be flowing back onto campuses and the data show there will be a lot more women than men in lecture halls. That continues a trend that analysts have been seeing for years now and it is reshaping the country and its politics.

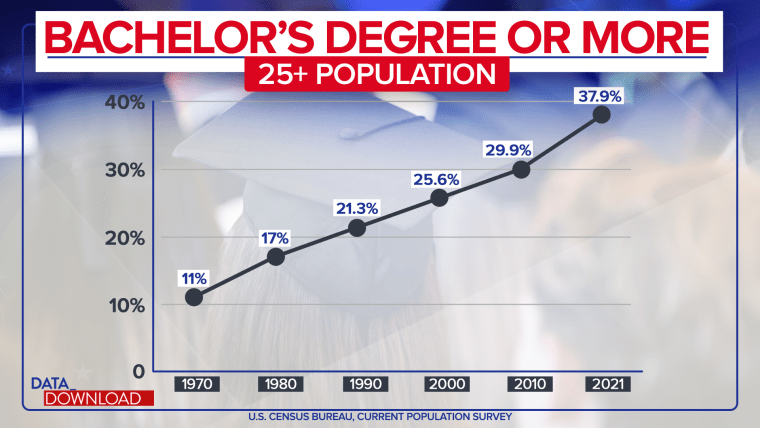

On the most basic level, the number and percentage of Americans with at least a bachelor’s degree has been rising steady, climbing nearly 30 points in the last 50 years.

Back in 1970, only 11% of Americans 25-or-older had a bachelor’s degree. The number has risen every decade to roughly 38% in 2021, according to the data from the Census’s Current Population Survey.

The jump since 2010 has been especially sharp and one of the big drivers of that has been more women completing their four-year degrees. In fact, in the last decade, women surpassed men in college completion.

In 2021, the Census found that the number of American women with degrees was about 3 points higher than the figure for men — 39.1% versus 36.6% respectively. And looking back at the history of those figures shows how remarkable that change is.

Back in 1970, about 8 percent of 25-plus women had a bachelor’s. That was about 6 points below where American men were at that time. The difference actually grew slightly in 1980, but then women began closing the gap, and quickly. By 2010, the two sexes were almost even, before women surged ahead in the years since.

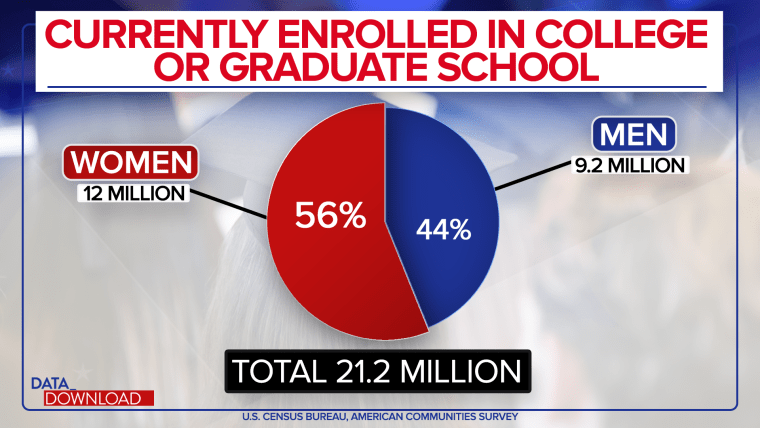

And to be clear, there is no reason to believe that trend is going to reverse any time soon. The latest college enrollment figures show a wide divide between the sexes regarding who is currently enrolled in college.

In 2021, the Census estimated there were about 21.1 million Americans currently enrolled in college, according to the annual American Community Survey. About 12 million of those people were female and about 9.2 million were male in that data. That’s a difference of about 2.6 million or a 56% to 44% split.

In other words, those current day figures certainly suggest the gap between men and women with college degrees is only likely to grow in coming years.

These data have a lot of meaning beyond who is paying tuition or paying off student loans. They have the potential to change who and how men and women marry (for decades data showed men married people of equal or lower educational attainment and women tended to marry those with equal or more education). And in the longer term, these numbers could have a real impact on who sits in the corner office in the business world. High-end positions tend to require more education and over time women seem more and more likely to be the applicants with degrees.

These figures also may have political impacts in the years ahead. Two of the biggest splits in politics in the last few decades involve sex and education and the college attainment and enrollment numbers look set to reinforce them.

Consider the divide between male and female voters. The “gender gap” in American politics, in which women lean solidly Democratic and men lean solidly Republican, has grown in recent decades and was notable in the 2020 election.

In that race, President Joe Biden won women voters by double digits, 15 points, and former President Donald Trump did very well with men, capturing them by 8 points, according to exit polls. That’s a partisan “gap” of more than 20 points between the sexes — big enough to impact messaging and campaign approaches — and there’s no reason to expect it to shrink any time soon. Abortion, an issue which resonates deeply with women, has grown as a focus with voters following the Supreme Court’s 2022 Dobbs decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade.

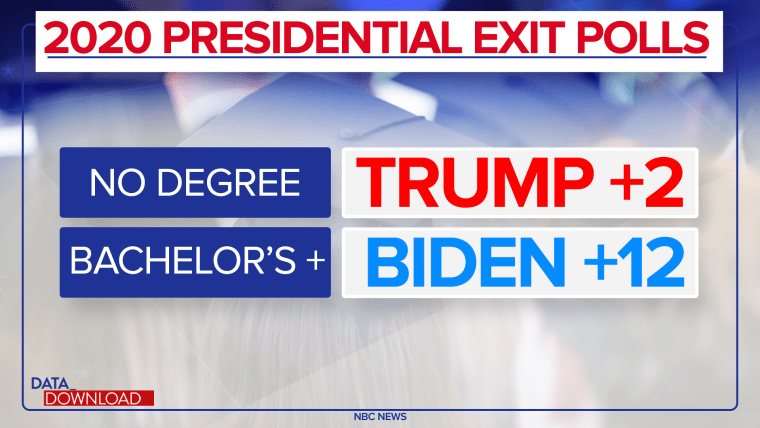

And educational attainment has become a significant factor in partisan affiliation as well. College graduates increasingly vote Democratic and that had big impacts on the most recent presidential race.

In 2020, voters with a college degree or more voted for Biden by 12 points — 55% to 43% for Trump, according to the exits. And voters without a degree selected Trump, albeit more narrowly, 50% to 48% for Biden.

Those political trends combined with the broader changes in who is going to and completing college may end up reinforcing each other and leading to a long-term shift where the nation’s two biggest political parties are increasingly divided by a mix of gender and education.

In 2023, politics is often talked about in terms of simple tribalism, a sport with voters who wear red or blue jerseys and just fight for their team. There is some truth to that. But underneath binary color code there are real differences that extend beyond politics, driven by voters who see and experience the world in different ways.

A woman with a college degree and a man without one may be driven politically by distinct sets of issues — economically and culturally — particularly in an economically unsettled time marked by big social changes and more limited government resources.

As students arrive on campus this fall those real-world gender/education differences seem likely to keep growing.