The UK’s maternal mortality watchdog, MBRRACE-UK, have published their 2023 report on the pregnancy and birth-related deaths of women (maternal deaths). The latest Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care report looks at data from the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity for women who died during or up to one year after the end of their pregnancy between 2019 and 2021 in the UK. It also highlights themes and concerns about the care of women who died from specific causes, including obstetric haemorrhage (bleeding), anaesthetic causes, infection, general medical and surgical disorders, and neurological conditions such as epilepsy and stroke.

MBRRACE-UK found that the overall maternal death rate increased between 2016-18 and 2019-21, but was similar if deaths due to COVID-19 were excluded. MBRRACE-UK said there must be better implementation of its recommendations if the UK is to reduce the number of maternal deaths.

Preliminary figures relating to the number of maternal deaths in 2019 to 2021 were released by MBRRACE-UK in a summary report earlier this year.

MBRRACE-UK’s statistics on maternal deaths from 2019 to 2021

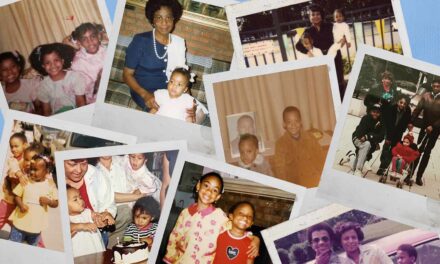

MBRRACE-UK’s statistical analysis of maternal deaths provides vital monitoring of harmful trends in maternity and post-natal care, and plays an important role in ensuring that the healthcare system recognises and learns from the experiences of those who died. It is also important that, as we read the following statistics, we remember that each woman’s death is a devastating tragedy with life-long consequences for the partner, children and wider family she leaves behind.

The report shows that 241 women died during or up to six weeks after the end of their pregnancy from 2019 to 2021, out of a total of just under 2.07 million mothers who gave birth. Just over a quarter (26% or 62 of these women) were still pregnant at the time of their death. The 241 deceased women left behind a total of 404 motherless children.

Of the 154 women who gave birth, 84% did so in hospital, 10% gave birth in an ambulance or A&E department, and 6% had home births. The most common causes of death were COVID-19, cardiac disease and blood clots, each accounting for 14%, followed by mental health conditions and sepsis (both 10%), the neurological conditions epilepsy and stroke (9%), with bleeding, pre-eclampsia, cancer and other conditions causing for the remaining deaths.

More than half (56%) of the women were known to have pre-existing medical problems, 37% had known pre-existing mental health problems, and 34% were obese, with a further 24% overweight. Maternal mortality rates were higher amongst older mothers and those aged under 20.

The risk of maternal death increased for those from Black or Asian ethnic minority groups and those living with deprivation. Compared with White women, 4 times as many Black women and twice as many Asian women suffered maternal deaths. The majority of women who died from COVID-19 in 2020 and 2021 were from ethnic minority groups. 12% of those who died during or up to a year after their pregnancy were at severe or multiple disadvantage, from mental health issues, substance abuse or domestic abuse. Women living in the most deprived areas continue to have the highest maternal mortality rates.

MBRRACE-UK’s assessors found that only 53% of those women who received antenatal care, received care which complied with NICE antenatal care guidelines. Only 14% of the 190 deceased women whose care was examined via the confidential enquiry reports were assessed to have received good care. The assessors believed that better care may have made a difference to the outcome for a further 52%.

Common themes highlighted by MBRRACE-UK’s 2023 report

One of the key themes which ran throughout MBRRACE-UK’s report was that failings in women’s maternity and postnatal care often reflected a ‘maternity system under pressure’. Within this theme, MBRRACE-UK warned that the risk of maternal death was increased by the fact that complex category 3 caesarean births (where an early delivery is needed but there is no immediate threat to the mother or baby) were often pushed back to late in the evening, after category 4 emergency caesarean births had been prioritised throughout the day. They recommended that elective (non-urgent) and emergency caesarean lists should be managed separately to ensure that senior team members are available.

Bleeding

Obstetric haemorrhage (bleeding) is a common complication of pregnancy and labour. The report highlighted that although mortality from haemorrhage is rare, the number of women dying from obstetric haemorrhage is not decreasing. Common failings in the care of women who died after haemorrhage (bleeding) included delayed recognition of the clinical signs of significant blood loss, delays in treatment, lack of senior leadership and a lack of overall (situational) awareness of the woman’s blood loss and deteriorating condition whilst staff were all busy focussing on individual tasks. The assessors found that there was incorrect and inappropriately prolonged use of vasopressors and balloon tamponade to control the bleeding, and women with massive haemorrhages were being denied essential blood clotting products by haematology staff based on inappropriate coagulation tests. MBRRACE-UK repeated their previous warnings that blood loss is often underestimated in women who have a low BMI, and recommended that the emergency response to obstetric haemorrhage must take into account the woman’s body weight when estimating her blood loss.

Women with an abnormally positioned or invasive placenta suffered owing to lack of specialist, critical or multidisciplinary care, poor communication, lack of advanced surgical skills or appropriately trained midwives, leaving them without adequate care in the event of a blood loss emergency. MBRRACE-UK also found that these women’s caesarean births had taken place at a later gestation than RCOG recommended and they were often monitored immediately after the birth by staff who lacked the necessary training and equipment.

Overall, MBRRACE-UK’s assessors felt that 62% of the women who died from bleeding might have had a different outcome with better care.

Anaesthetic care

MBRRACE-UK emphasised that the maternal death rate from anaesthesia as a direct cause is extremely low, despite the fact that 59% of all women who give birth have an anaesthetic procedure. There was only one maternal death directly caused by anaesthesia between 2019 and 2021, but the assessors identified several cases in which the anaesthetic care could have been improved. These included instances of obstetric haemorrhage where the anaesthetic management of resuscitation could have been improved or where the anaesthetist’s involvement in the woman’s care was delayed. The report identified delays in involving anaesthetists in the care of critically unwell women as a recurring theme, such as delays in escalating deterioration until the final stages, or failure to refer a woman with comorbidities to an anaesthetist antenatally to allow for multidisciplinary planning of her care in labour.

Infection

Pregnant women have an increased risk of infection owing to changes in their immune system to support the development of the unborn baby. Invasive procedures during labour and birth also increase their risk of developing infection. There were 78 maternal deaths from sepsis/infection in the UK and Ireland from 2019-2021, with COVID-19 the leading cause. MBRRACE-UK assessors noted that many of the women who died from COVID-19 were not vaccinated or their treatment hadn’t complied with the guidelines.

MBRRACE-UK emphasised the importance of early recognition and treatment of sepsis, particularly as pregnant and post-natal women are known to be high risk for sepsis. They found that delayed giving of antibiotics to women with sepsis red flags was a recurring theme and reiterated that the guidelines recommend giving intravenous antibiotics within one hour of suspicion of sepsis, whether or not the patient has septic shock. Other common failings included attributing symptoms of sepsis to other causes, specialists limiting their care of the woman to their own expertise without taking action to clinically assess the patient’s condition, and lack of multidisciplinary involvement from senior clinicians. The assessors also identified a lack of urgency in delivering women at risk of sepsis who then deteriorated.

The report emphasised that maternal survival in sepsis is dependent on early recognition of clinical deterioration, with early diagnosis, treatment and organ support. For this to happen, there must be clear processes for escalation, rapid senior multidisciplinary review, accessible critical care facilities and appropriately trained staff to look after the critically ill woman, as well as processes in place to deal with any obstetric emergency that takes place in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Women with medical or surgical conditions

From 2019 to 2021 in the UK and Ireland, 21 women died during or up to six weeks after pregnancy from conditions such as diabetes, blood disorders, respiratory conditions such as asthma, and gastrointestinal disorders. Many of the women who died from their other medical conditions (co-morbidities), particularly diabetes, were extremely vulnerable. The assessors found that midwives were often expected to care for vulnerable women with complex and multiple conditions, including in recovery from theatre, when they had not been trained to do so. This meant that the severity of the woman’s condition was not recognised. The report reiterated that, unless there is a clear reason, pregnant or breast-feeding women with co-morbidities should receive the same level of care as non-pregnant women. The assessors felt that better care might have led to a different outcome for 47% of those with co-morbidities or medical or surgical conditions.

Neurological causes

42 women died during or up to a year after pregnancy from neurological causes. 17 died from epilepsy-related causes, of whom 14 died from Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP), nearly doubling the rate of SUDEP since 2013-2015. Lack of adherence to anti-seizure medications was a recurring theme. There were also significant gaps in care, particularly for women with multiple or complex health conditions. Some women received no input from neurology/epilepsy services.

Other neurological causes of maternal death included delayed diagnosis and treatment of stroke, subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) and intracerebral haemorrhage. For many of the women whose care was assessed, their headache symptoms late in pregnancy, during or after birth were not recognised until they were catastrophic. MBRRACE-UK emphasised that persisting, acute or severe headache and focal symptoms (such as seizures) are red flags, and when they occur in pregnant or post-natal women, they require immediate action and escalation. The assessors felt that better care might have made a difference for 26% of the women who died from neurological causes.