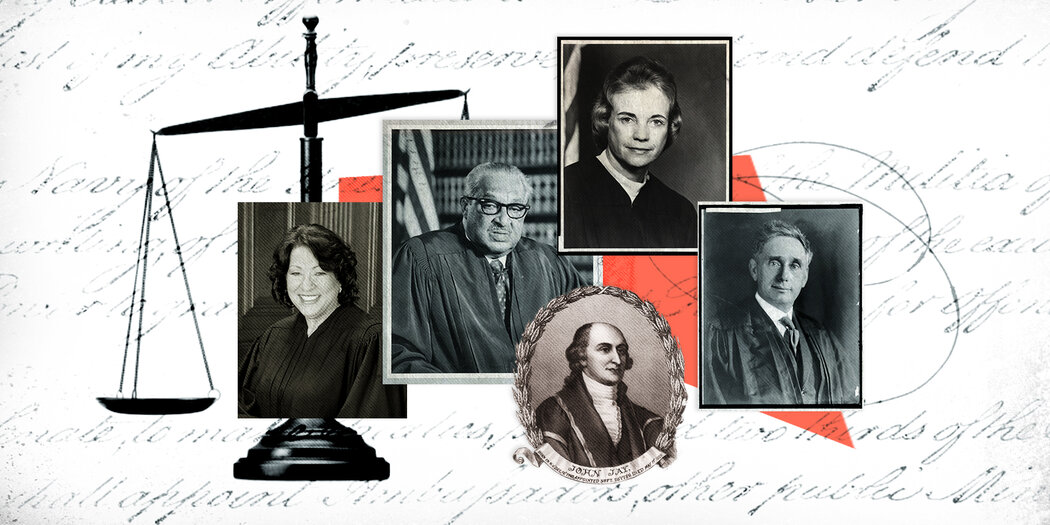

The First Black Supreme Court Justices

Thurgood Marshall, the prominent civil rights lawyer, was appointed by President Lyndon Johnson as the nation’s first Black Supreme Court justice in 1967.

Marshall, born in 1908, was raised in racially segregated Baltimore. A rambunctious student, his punishment in high school was to sit and read the U.S. Constitution, which he memorized by graduation. Marshall attended Lincoln University, a historically Black college in Pennsylvania, but was denied admission to the University of Maryland Law School because of his race.

At Howard University Law School, where Marshall graduated first in his class, he was mentored by the university’s dean, Charles Houston, who taught Marshall that the best way to end racial discrimination was through the Constitution. Together, the two men joined the NAACP’s legal team. In one of Marshall’s first legal cases, they successfully argued that the University of Maryland Law School’s racist admissions policy was unconstitutional.

In 1940, after Houston returned to private practice, Marshall launched the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund and began methodically chipping away at the legal basis for the “separate but equal” doctrine upholding racial segregation in the South. Marshall argued and won a series of landmark Supreme Court cases, but none as impactful as Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which effectively ended the legal segregation of public schools.

Marshall brought his commitment to civil rights and social justice to the Supreme Court and argued repeatedly to end capital punishment and expand programs such as affirmative action. He retired in 1991 and was succeeded by the second Black Supreme Court justice, Clarence Thomas.

Thomas, like Marshall, grew up in the racially segregated South. He had originally planned to become a Catholic priest but left the seminary to pursue a career in law. He was accepted to Yale Law School in 1971 as one of the first Black students to benefit from affirmative action. His mistreatment by white classmates, who implied that he only was admitted because of his race, fueled Thomas’s lifelong opposition to affirmative action.

Under President Reagan, Thomas was appointed assistant secretary for civil rights in the Department of Education and then chair of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. In 1990, President George H.W. Bush appointed Thomas to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

When Marshall announced his retirement, Thomas was 43 years old and had only been a judge for one year. Thomas’s confirmation hearings were some of the most contentious in history due to accusations of sexual harassment by a former employee, Anita Hill. He was ultimately confirmed by a vote of 52–48.

As a Supreme Court justice, Thomas became famous for almost never asking questions during oral arguments — he went a full 10 years without saying a word from the bench, although he is now a more active participant in oral arguments — and his staunchly conservative reading of the Constitution makes him a core part of the Court’s conservative voting bloc. More recently, Thomas has come under public scrutiny for several ethics scandals, including allegations that he accepted luxury gifts and trips from GOP megadonors and that his wife, Ginni Thomas, participated in the effort to overturn the 2020 presidential election results.