2023 is a milestone year for the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT) and its artistic director emerita Judith Jamison. On May 10, Jamison celebrated her 80th birthday, and on Nov. 29, the dance company will hold its annual opening night gala celebrating its 65th season; founder Alvin Ailey and a group of Black dancers first performed under the AAADT name in New York City in March of 1958.

“Numbers and ages really do matter,” says Jamison, a Philadelphia native who began dance training at the age of 6 at the Judimar School of Dance. “I love when people say, ‘The number doesn’t matter.’ Oh, yes it does when you’ve been dancing most of your life. It matters a whole lot because your body is catching up to what craziness you were doing as a dancer. At 80, everything doesn’t work the same way. And that’s the challenge, finding out, what can I do? What can’t I do? But I’m loving it.”

AAADT will pay homage to Jamison’s tenure as artistic director of the company from 1989-2011 during its November opening night gala and again on Dec. 19 when it premieres its “Pioneering Women of Ailey” program with special performances celebrating her alongside fellow Black women dancers Carmen de Lavallade, Denise Jefferson, and Sylvia Waters.

“One thing I can tell you is I have always been and will always be in awe of one of the most fabulous artists that I’ve ever had the privilege of working with, and that’s Carmen de Lavallade,” says Jamison. “She doesn’t get enough said about her. She’s a total icon. And she’s done everything. She’s been a guest artist with American Ballet Theater, she was doing a one-woman show when she must’ve been 80-something. My hat is off to her.

“When I think of some of the things I’ve done, for me, they’re on a good level,” Jamison adds. “I’m not belittling what I’ve done, but all of us have contributed something very different, and I always consider them to have contributed even more than I have.”

Jamison talks to THR about learning from Ailey, working on Broadway with the likes of Gregory Hines and Mercedes Ellington and how she was discovered.

When you joined the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 1965, did you have a sense that it was the beginning of something great for you?

No, I didn’t have any revelations like that. I was like a kid in a China shop. Agnes DeMille discovered me in Philadelphia. Everybody thinks Mr. Ailey brought me in but it was Agnes DeMille. We did a piece called The Four Marys and my first gig was as a guest artist with American Ballet Theater. So, I’m in New York for the first time. By the time Mr. Ailey saw me at this audition for a Harry Belafonte special that Donald McKayle was choreographing, I thought, “Are you kidding me? This man is calling me to ask me whether I’d be interested in doing this. Yes!” And when I walked into my first rehearsal, I was put very much at ease by James Truitte who I’d seen dance. He was one of the original members of Ailey, and I had seen him perform already. But I walked into this small rehearsal studio at the YWCA on the West Side, at 50th and 8th Avenue, and in each corner of the room, somebody was learning something. My eyes were wide open, and I was fascinated. There was no time to go, “Oh, this is a pivotal time in my life.” It’s only in retrospect that that happened.

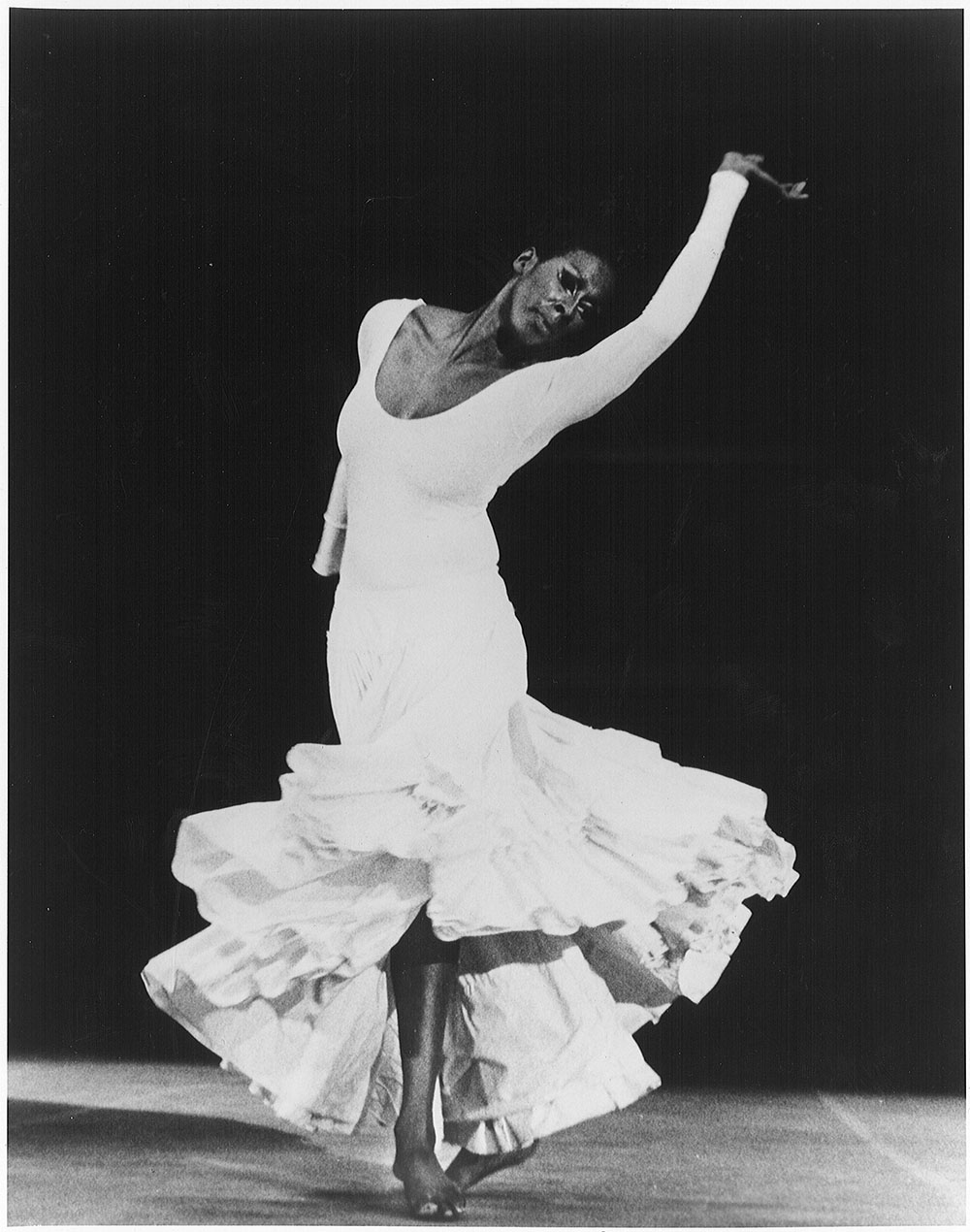

Six years later you performed Cry for the first time, a piece Ailey dedicated to Black women that has gone on to be one of the signature choreographies of the company. What do you remember about that night in 1971?

I didn’t think anything unusual had happened when the curtain went down, except people kept applauding. We had gotten that before, but not by myself with a standalone solo. So when I did Cry that night, I hadn’t run it from beginning to end, so I didn’t know what it was going to do to me. And God bless the late Dudley Williams because he saw that it looked like my legs must have been jelly when it came to that last section, and he came from the back of the theater to stage right and just his look and his enthusiasm and how he was using his arms. He was encouraging me, “Keep going, keep going, keep going.” They still do that to this day, the dancers, whenever a young woman does Cry. There’s so much enthusiasm that at times when I was AD [artistic director], I had to tell them, “Okay, shut it down, y’all. The audience is going to hear you cheering the person on.” But that care and that love is there to get you through no matter what. And when the curtain went down, I was on the floor. I literally fell out on the floor. Emotionally, physically, and spiritually it wears you out if you really put your whole self in it. So the curtain went down, there’s lots of applause. Of course, as a performer, there’s no way they’re going to raise the curtain up and you’d be lying on the floor, so I get up and I take a bow, and I kept taking bows over and over until I don’t know which number it was, but they were still screaming and yelling.

I still didn’t find anything particularly unusual until Mr. Ailey came backstage, and he said, “What I do next? I don’t even know if he knew it was going to go where it went because you don’t choreograph thinking, “Let me make a hit.” You choreograph out of the depths of your soul and your spirit and your honesty and your truth and your gut. And it could fall flat on its face, you know? But it didn’t. I was older so it didn’t happen to me when I first joined the company and I think that was wonderful, but I still got sucked in because it becomes a whirlwind. Young people don’t understand once you reach that level of people really loving you and then the press gets a hold of you, it takes you to places you have never been. People are surrounding you that never surrounded you before. You have to make decisions.

How did you handle that?

I had a lot of guidance. And I still did stupid things, but I had some really good guidance. The agent for the company, his name was Paul Szilard, he died when he was 99 years old. He was marvelous, we called him the last of the impresarios because he was. And he became my agent as well. So there was protection there. We also had a press person in place who had been working with the company for years, and she stepped forward and covered the bases that needed to be covered so I wouldn’t get swamped. You have to disseminate between what’s real and what’s temporary, what will pass in a minute, in a heartbeat. And you can’t afford to let your feet come off the ground. Keep your feet on the ground and stop trying to float. You’re dancing, you’re performing, you’re trying to get this message across. It’s not your life. To this day, it’s still hard for me to get a cab. That keeps you pretty grounded.

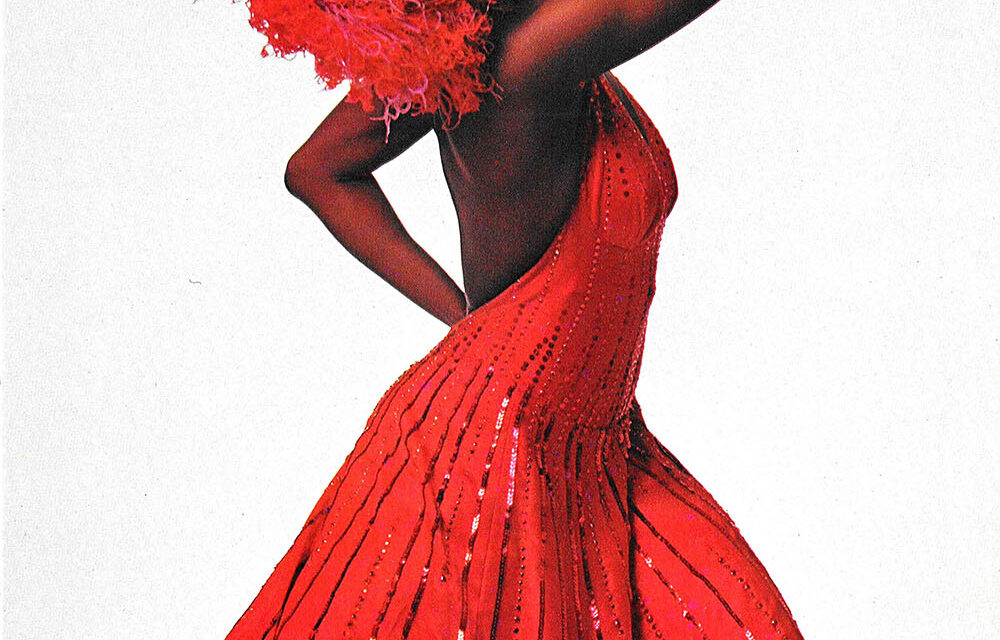

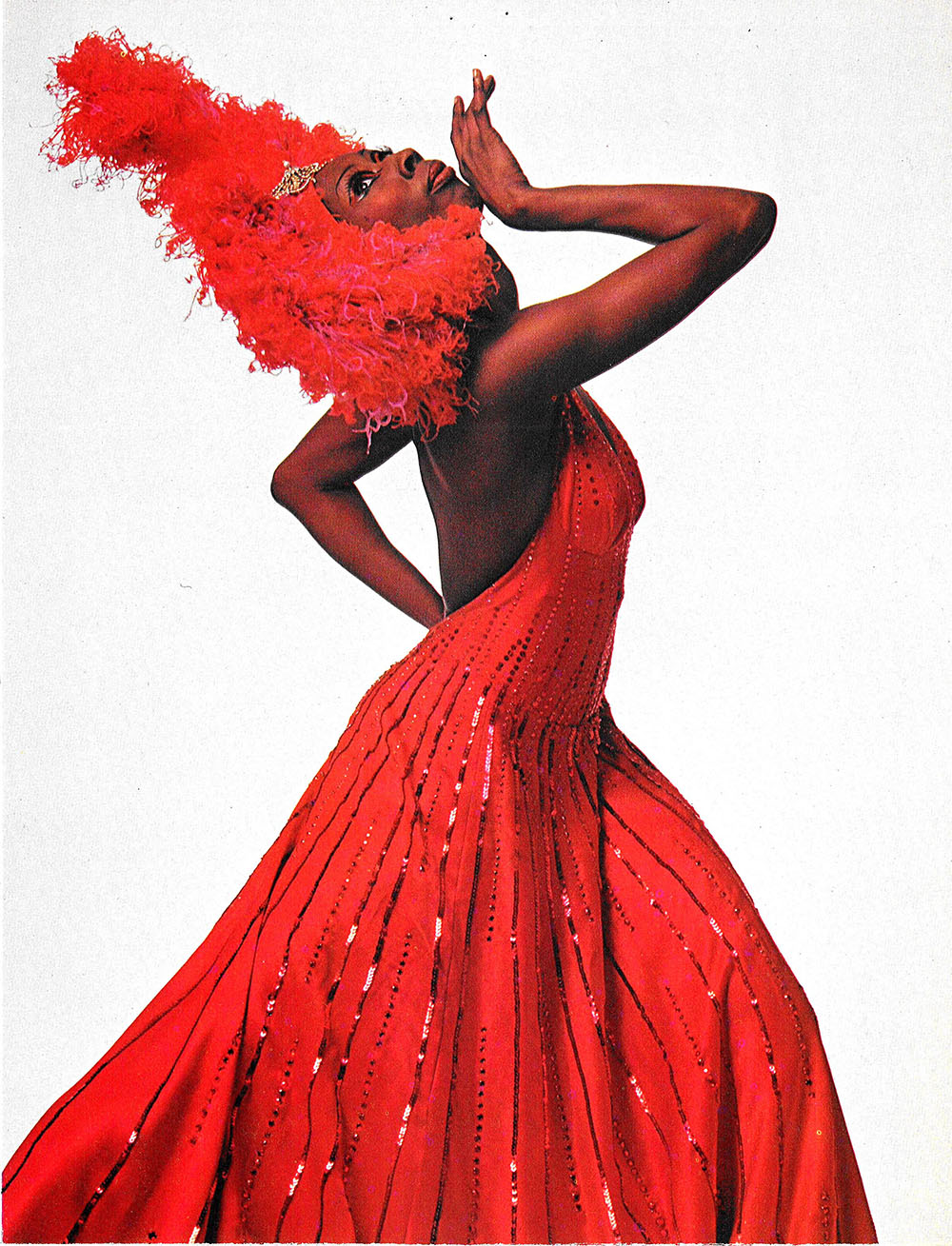

Judith Jamison in Alvin Ailey’s The Mooche.

Henry Wolf

How did your experience on Broadway and with other ballet companies compare to your time with the Alvin Ailey agency?

With Broadway, it was a completely different discipline. Can you imagine working with Gregory Hines? That was a real fantasy for me, and it was there every night. That was a very interesting period in my life. I learned a lot, not just from him, but from Mercedes Ellington who was in Sophisticated Ladies. There were always people around you that would keep you walking the right way, like bumpers. I call them spiritual walkers. They keep you on that path that you’re supposed to be on. When you’re performing, that’s a privilege, number one. But also, it’s a matter of giving, not a matter of going inside yourself so far that nobody knows who you are. There’s always a reciprocity to performance. You have to go in, but you have to give it out. You have to give it back because you’re not dancing in a vacuum. Just being excellent and people throwing accolades at you is passing. Stage is your heart and soul and mind and the love that you have for people. Mr. Ailey showed that to us right away by demonstration. You could see how much he loves people; he wasn’t dancing just to show himself off.

Broadway was eight shows a week of what I thought in the beginning was the same thing over and over and over again. What woke me up was one day I came out on stage and my first entrance was just walking out and meeting Gregory. And he would gesture to me, and his hand would be standing there, and for some reason I was looking at the bottom of his hand instead of the top of his hand because I tripped. My heel caught in my skirt, and I fell flat on my face. First entrance. And that’s when you wake up and ask yourself, well number one, where’s your head that you can all of a sudden fall flat on your face? That means you’re taking for granted that you’re doing eight shows a week and thinking that eight shows are the same thing. You’re not considering the audience. You’re not considering your fellow artists that are dancing. You’re not considering the whole entity of performance. It’s a completely different discipline than concert modern dance and just as important. And I got straightened out real quick.

Judith Jamison in Alvin Ailey’s Cry.

R. Faligant

Talk about coming back to AAADT and the day you assumed the role of artistic director.

We were in St. Louis in 1988. I was in a restaurant with Mr. Ailey, who had invited me to lunch. He had asked me to come on tour with the company and I knew he was ill. I hadn’t been on tour because I’d started the Jamison Project and he basically, just said, “I’d like you to run the company.” And I said, no question, “Sure.” It was no question because I’d been working with him from ’65 and seeing him live since ‘63 in Philadelphia when I was in college. This man, I loved completely. I absolutely loved him. And when he said that to me, it’s like, what do you, you know? That was simply it. And by ’89 he passed.

What were some of the biggest challenges stepping into that role?

Well, for the first two years, I wouldn’t say there were many because the only thing that was in mind was this is going to stay afloat, and we were going to honor and elevate and make sure history understands who this man was by our existence and by our excellence and by our love for what we do. But it was a whirlwind because when I took over, we were in a lot of debt. A lot of debt. Ironically, the debt was coming from honoring someone else. He was so dedicated to making sure that this person was honored, and that person was Katherine Dunham. In order to put these productions on, it costs a lot of money. And by the time I took over, it was difficult. But when I think back on it, I didn’t think, “Oh, how am I going to do this?” I’m doing whatever I have to be doing. I’m already in it. So there’s no time to go, “Now what do I do?” It’s just, do. I never go down that route. I don’t understand why anybody would go down that route because you’re not going to get anything done. Most of us want to go back. But if you’re in a whirlwind, you don’t have time.

First Lady Michelle Obama introduces Judith Jamison during a 2010 tribute to the renowned dancer, choreographer and artistic director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, at the White House in Washington.

Brooks Kraft LLC/Corbis via Getty Images

Of all of the accolades you’ve received personally and as part of the company, are there any you’re most proud of?

Seeing the company dancers each generation. Every generation that comes speaks to the genius of a man named Alvin Ailey. We’re getting farther and farther away from people even knowing him, not seeing him, meeting him, anything, and every generation has to continue the legacy and love it, and if they don’t, they need to go someplace else. So the more I see these young dancers who can do so much more technically than we ever could be, I’m inspired to let them. I always am proud of them when they do come to a revelation about Revelation, about Blues Sweet. When that light bulb finally goes on, your dancing changes in ways. And when you’re challenged by all the other repertory that’s in the company—there’s got to be over 200 now because Mr. Ailey did 75 — when you honor that, and you know how important it is to not have your history erased like people are trying to do again. When you realize that you can’t have that happen, you can’t let anybody do that to you, the way you keep that up is to educate yourself, love what you’re doing, be excellent about what you’re doing, and keep a good sense of humor. People forget that sometimes.

Mr. Ailey used to remind us if we got too all high and mighty in our heads, “You know you’re a dancer?” He’d say it in such a way that wasn’t derogatory, but it was loaded with, look, this is a privilege for you to be able to get on stage and make a living doing these things. And you should enjoy that and understand how privileged you are to be gifted with these God gifts that are given to you. So enjoy it. And have some levity.