Josephine Baker (left), Mollie Moon (right) and the newly crowned Miss Beaux Arts Ball, 1960.

E. Azalia Hackley Collection of African Americans in the Performing Arts/Detroit Public Library/Amistad imprint of Harper Collins

E. Azalia Hackley Collection of African Americans in the Performing Arts/Detroit Public Library/Amistad imprint of Harper Collins

When we think of the Civil Rights Movement, opulent parties are probably not the first thing that come to mind. But it turns out, they were a big part of the fight for racial justice — especially the events organized by Black socialite Mollie Moon in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s.

Known as one of the most influential women of the civil rights era, Moon served as president of the fundraising arm of the National Urban League and is credited with raising millions to build economic and racial equality in the U.S. But historian Tanisha Ford says she only heard of Moon accidentally, while doing research for another project.

“I stumbled across the name Mollie Moon in the newspaper clippings of the early 1960s. … She was hosting this amazing beauty pageant that celebrated the beauty of Black women,” Ford says. “So I just tucked her name in the back of my mind and thought, ‘I’m going to write something about this woman.’ “

As Ford gathered press clippings about Moon, she realized there was a larger story to be told, “one that made people aware of this great leader of the Civil Rights Movement who had fallen out of the narrative.”

Moon’s New York City parties attracted stars like Billie Holiday and Josephine Baker, as well as wealthy white donors, Black elites and working class Black people. But Moon faced criticism from activists who were skeptical of taking money from rich white liberals.

“What African Americans feared was that that kind of influence would then steer the movement away from the issues that African Americans cared about and … toward issues that felt safe for white Americans,” Ford says.

Ford notes that debates about money, influence and social justice are still relevant today. But, she adds, fundraising is a crucial — and often-overlooked — part of the Civil Rights Movement.

“I have found that once I started to turn my attention to the money, that this story humanizes these people even more, and it makes the stakes of movement building all the more clear,” Ford says.

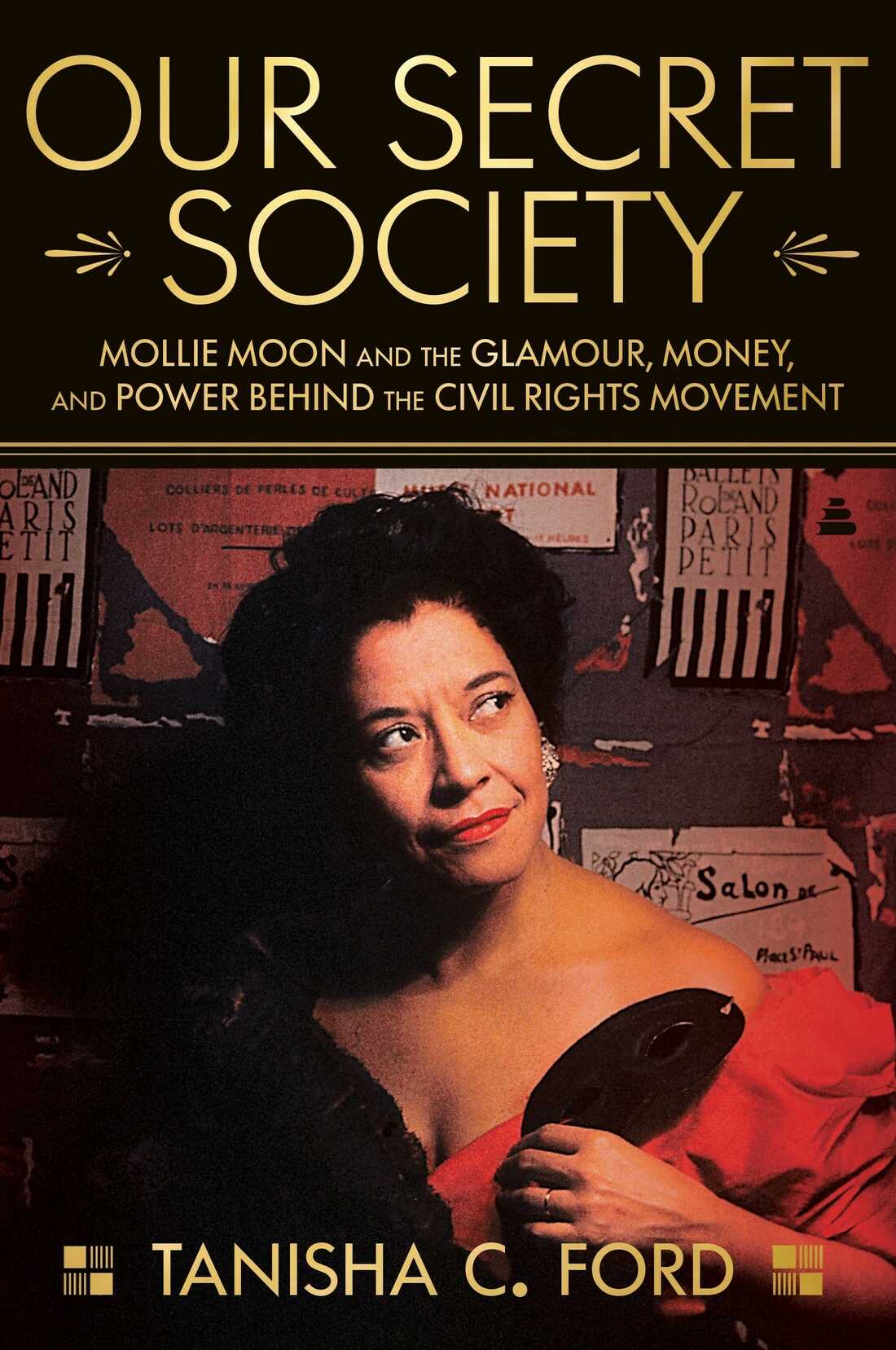

Ford’s new book is Our Secret Society: Mollie Moon and the Glamor, Money and Power Behind the Civil Rights Movement.

Our Secret Society: Mollie Moon and the Glamour, Money, and Power Behind the Civil Rights Movement, by Tanisha Ford

Harper Collins

Harper Collins

Interview highlights

On Moon’s celebrity-packed parties

These parties, by all accounts, were fabulous. Her signature event was the Beaux Arts Ball. She would host that event every year since 1940, and it was an event that started off in Harlem at the Savoy Ballroom and then moved in the 1960s, the early 1960s, to the Astoria Hotel in midtown New York. And these events brought together all sorts of people, as you mentioned, everybody from weary subway workers and domestic laborers to titans of industry, including the Rockefeller family, people like Billie Holiday. Katherine Dunham at one point was a sponsor for the event. I even found in the records where she had invited the Duke and Duchess — the former king of England [Edward VIII] and Wallis Simpson — to be judges for the costumed affair portion of the Beaux Arts Ball.

On the programs funded by the National Urban League

They were funding everything from voter registration drives to things like the March on Washington, but also Black youth programs. Mollie Moon’s degree was in pharmacy, and before she went into social work, which became her long-term career, she had a dream of becoming a biology teacher. So she was deeply invested in what today we call STEM. And so a lot of the funds went toward funding Black youth, for them to have educational programs. And then other things funded journalists. So their fundraising efforts funded a wide array of social-justice oriented, racial-equality-minded events that have had a deep impact on community building in the African American context.

On journalist Lillian Scott’s criticism of Black people networking with wealthy white liberals

[Scott] does represent that generation of younger, more radical Black journalists who are saying, “Hey, wait a minute. We have to remember that the wealth that the Rockefellers and others of these elite families who are clamoring to support the National Urban League have amassed has come from a system of slavery.” … And Lillian Scott was saying we should not be seduced by the fancy gowns and invitations to party in the Rainbow Room because African Americans, by and large, are still living in abject poverty in this nation. And a fancy party is not going to undo generations of economic disparities. So she … would use her column in the Chicago Defender to talk about these issues of race and class and gender and really discuss them in a complex way, but using the cheeky form of the society pages to do it. So her columns are a true gem in terms of understanding the nuances of these race and class dynamics in the mid-20th century.

On the criticism of white philanthropy — then and now

One of the concerns then, that remains now, is that there shouldn’t be an accumulation of wealth to begin with, but that even funneled into movements that oftentimes creates a kind of stagnation where the money isn’t being then redistributed to the communities that need it most. So there is a structural issue in terms of how we even approach fundraising for the movement: Who gets the money and what kind of time period is considered acceptable for the money to be redistributed to Black communities? So that concern was definitely there.

Tanisha Ford is a professor of history at The City University of New York.

Darcy Rogers/Amistad imprint of Harper Collins

Darcy Rogers/Amistad imprint of Harper Collins

The other piece of that is, well, once the moment passes, if we have become dependent upon this white hand of philanthropy, then what do we do then when white people decide that they no longer want to give this money to our cause? And this is another thing that we’ve seen play out in the present moment, where in 2020 there was a surplus of money being given to organizations like BLM and the National Urban League and the NAACP, who received even more money than BLM did, to be clear. But what happens in 2021, 2022, 2023, where we start to see a retrenchment in terms of the kinds of money that’s being given to racial justice, almost to the point now where saying “racial justice” is like a dirty word, even though it was so en vogue just a couple of years ago?

On the lesson of Moon’s life

A photograph of Mollie Virgil Lewis (Mollie Moon), circa 1926.

Henry Lee Moon Family Photographs, Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio./Amistad imprint of Harper Collins

Henry Lee Moon Family Photographs, Western Reserve Historical Society, Cleveland, Ohio./Amistad imprint of Harper Collins

The longer I sat with Mollie Moon’s archive — with her letters, with her personal keepsakes, looking at photographs of her — I realized just how brave this woman had to be to be so unapologetically herself in a time period where Black people were being persecuted daily, for the color of their skin. And if there is anything that I think Mollie Moon would want us to know, it is that every human being on this earth deserves to be able to walk in the fullness of themselves in the fullness of their humanity. And I think that her mission of Black joy, a Black joy that so contagious that everyone in the world would benefit from that kind of joy, is one that really resonates today. That if we could just step outside of ourselves long enough to recognize the suffering of someone else and be willing to sacrifice something of ourselves, whether that be a small dollar financial offering, whether it be volunteering our time, whether it be calling a congressperson, that if we were willing to do that for someone else, then we have the power to make the kind of change that we need to see in this world.

Heidi Saman and Seth Kelley produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Bridget Bentz, Molly Seavy-Nesper and Meghan Sullivan adapted it for the web.