Growing pains come with the territory of urban spaces. Philly, one of the country’s oldest cities, tapped Brooklyn to gain ideas in its ongoing redevelopment.

Philadelphia, like many working class metropolises, is made up of old world identities and distinctively marked communities navigating smart age technology. In a post-industrial and now post-pandemic era, the Birthplace of America has yet to find its economic legs. When it comes to developing an effective and equitable plan in the digital age, the task becomes even more challenging. In a sense, Philly is a dinosaur. But like all dinosaurs, the city has good bones.

It’s these very same bones that the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia (the Economy League) has been preserving and building on since 1915. “We are tackling issues of inclusive growth and racial equity head on,” wrote Jeff Hornstein, the Economy League’s executive director. His commitment at the organization is to foster “a culture of civic experimentation and innovation [while] opening doors to civic participation.”

For years, the region’s independent “think-and-do” tank has been organizing an annual interactive leadership experience called the Greater Philadelphia Leadership Exchange (GPLEX). It operates with a simple premise—leadership learns from leadership by swapping ideas.

Instead of the stuffy suit-and-tie networking snooze, participants embark on a trip to another city to explore and gain a deeper understanding of best practices while with hometown affluentials. Sort of like multiple master classes, it is all done in situ.

This year, the Economy League deviated from their annual big trip to coordinate an additional smaller, and more local version of GPLEX. For this amended approach, 40-plus participants packed two days of clothes, hopped on a charter bus then headed to Brooklyn. At the end, the conversations and ideas flowed like a vintage hip hop song—absolutely magnificent.

Ark Republic was invited to shadow the group’s two-day BK excursion, which resulted in a mini, four-part series for our newsroom. Through the exchange between Philadelphians and Brooklynites, the series takes a glimpse into how movers and shakers are redesigning the fiscality of cities that reflect a changing America.

Get on the bus

Sometime in mid-June, Philadelphia and Brooklyn had a 36-hour conversation. Luckily, it wasn’t a sporting event, as there would be little left of the participants to exchange—literally. Philly carries a notorious reputation of breeding die hard fans. So much so, on game days, residents warn others to stay off of the roads if any of the local teams lose, but especially the Eagles. Added to the mixture of loyalty are the bragging rights of its historical weight.

On the other hand, Brooklyn is anything but the scruffy younger waterfront. A once blue collar enclave of mafia, broguish dock workers, Gullah Geechee southerners and Jewish mobsters, the political and economic power produced there has had so much impact that movies are made out of it.

Rather than a pugilistic camaraderie, on pick up day for GPLEX, it was a motley crew of non-profit executives, entrepreneurs, investment firms, and civic administrators in soft-soled shoes, khakis and designer sunglasses. Drinking iced coffees while making small talk, they gathered on a corner in Philly’s Center City for a charter bus headed to the 718.

Ninety-eight miles—a distance long enough for a city and borough to craft their own republics, but close enough to share characteristics and social genetic histories such as: gentrification, globalization, deindustrialization, immigration, burgeoning creative classes, and bustling small business ecosystems. Though both municipalities were tested during extreme social-political and economic shifts, their complex pasts speak of the sinew of palpable, local economies.

The ride to Bucktown was a perfect intermezzo from one urban sprawl to the next. After the bus inched past rush-hour hub-bub to finally coast on Interstate 95, the collective immediately fell into speedy introductions followed by long exchanges that had already begun at the impromptu bus stop. One such conversation was with Hornstein.

For him, at the core of Philadelphia’s revival would be equity. With years representing labor unions, Hornstein pointed out that workers in various professional trades became some of the fiercest challengers to the city’s most resourced, and obstinate institutions. In these battles, it became evident that segregation, racialized wealth gaps and racism turned out to be a costly enterprise even for cities in the North.

Hornstein’s vision is to institute restorative initiatives at every point and planning of the city. GPLEX, he hopes, opens up better ways to remedy generations of invidiousness that still have current ramifications. “There are older Black women who did everything right … worked hard, saved their money and bought homes,” cited Hornstein about the maintenance workers he represented during his time with unions. “But they’re homes are not worth what they should be.”

The disparity in the market value of homes can be as significant as hundreds of thousands of dollars. Especially, when comparing predominantly white, middle-class neighborhoods to predominantly Black and Latino working and professional-class communities that hold the same, or even more sweat equity in homeownership. The contrasts stick out even more when some of these districts share borders.

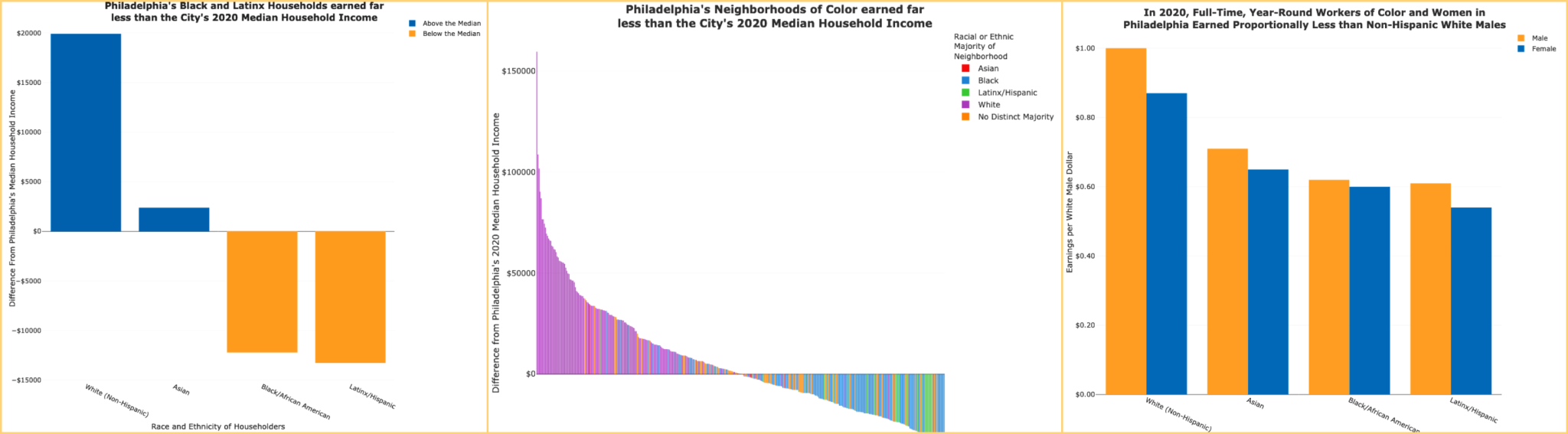

A glaring example of income equality is found in a report published by the Economy League. It showed that the majority white, non-Hispanic households made roughly $20,000 over the median income ($32,000) in Philadelphia, while Asians made $2,000 more. However, Black and Latino families scored $12,215 and $13,270 below, respectively. Additionally, workers of color and women earned less than white, non-Hispanic males.

⚈ ⚈ ⚈ ⚈

Much like Philadelphia, Brooklyn struggles with balancing equity and growth. “It is a very uncomfortable conversation,” Lindsay Green, CEO of Brooklyn Navy Yard said on a panel discussion outlining the arduous task of bringing underrepresented entrepreneurs to the center of the borough’s important economic dialogue. “But that is my job, to make it uncomfortable, so that we can get to real equity and inclusion.”

Added to the work is dealing with the transient nature of citylife. Both places speak of the volatility experienced by outgoing-and-incoming migrant groups. While some were voluntary, often those who were the most vulnerable were forced to leave. Then those who did stay through the multiple phases of inner city blues; subsequently, were afforded limited opportunities to fully advance. Generations later, the impacts remain significant.

This reality became more complicated after the pandemic when Philly turned into a desired relocation place for New Jerseyans and New Yorkers. While most outmigration from urban spaces during COVID-19 was experienced in regions such as the mid-Atlantic, Philadelphia went through a bust in employment opportunities, but a boom in housing. Resultantly, the economic quandary leaves the average native resident outhoused and outbid by the steady flow of Big Apple and Garden State newcomers.

Getting into the intellectual weeds of power with Hornstein, the time on the bus planted a seed of discourse on what Philadelphia ultimately needed, until the charter slowed then stopped. We had made it to the Republic of Brooklyn.

Breaking bread

After checking into a Marriott ensconced in Carroll Gardens, a neighborhood holding elements of an old Brooklyn, and the signature gentry settlers, we headed to dinner at F.O.B., a Filipino BBQ restaurant serving uncomplicated, but delicious island comfort food.

The corridor of Smith Street where F.O.B. nestles between other ethnic eateries, is a reminder that soul food means many things in Brooklyn. Located at the southwestern part of the borough, which is a piece of Red Hook, Carroll Gardens once hosted Irish and Italian immigrants. Recently, the neighborhood has attracted a highly-educated French class and other Francophone émigrés who add boulangeries and Bastille Day to the menu of locally observed, international holidays. Yet and still, etched into the memories of the streets are the nightly smells of Sicilian grandmothers and aunties cooking stews, pastas, succulent meats, and fresh fish from the day’s catch.

Quietly taking it all in is Harry Hayman, Senior Fellow for The Food Economy and Policy at the Economy League. With a long, deep-rooted career in hospitality, the restaurateur is the backbone of multiple food startups and several supper clubs that fuse his expertise in food, jazz and community. Hayman is on the GPLEX tour to see how Philadelphia can reamplify its lauded food scene by capturing the finest victuals of local, modest sized proprietors, as well as larger eating houses. From his lens, neighborhood nosheries narrate the finest stories of a metro because histories and cultures are often learned through culinary traditions.

Hayman mentioned that his fellowship allows him to explore ways Philadelphia’s food industry can recover and expand after a global pandemic shuttered many restaurants in the city. Even his beloved Warmdaddy’s, which had survived the initial economic dings of the pandemic, was eventually forced to shut down. While there are a number of investors who would love to pair with a respected industry veteran, Hayman is the type who entertains ideas that hold depth and sustainability. So on that night, he carefully samples the dishes offered at F.O.B. and contemplates.

Over shared plates, bottles of wine and smooth tequila brought into the B.Y.OB. establishment, the collective began again, speaking of Philly and what its old bones needed to evolve. Between plucks of chicken and marinated tuna, the group of influencers went Afro-futuristic. There was a concurrence that the City of Brotherly love had already bottomed out. Now in the “fix it” age, they began to imagine a cityscape that held signature identities and rugged determination, all the while, weaving in generous elements of advancements that provided both citizens and institutions the agency and tools for significant expansions.

“Having those conversations about the City over dinner was very affirming,” Chris LaPointe of We Love Philly told Ark Republic. “It felt like I belonged in the conversation; especially as someone on the ground doing work with teens. Listening to what everyone was saying . . . and we were all flowing off of each other even though we had different perspectives, but [still] respecting them was really cool … and my work was affirmed.”

In the casting of a future Philadelphia, dinner guests brought to the table, heaping conceptualizations of what they saw would forge the city into better cuts of itself. Some thoughts offered were tech-forward schools; industries incorporating digital landscapes; an adaptable and competitive economy; and both commercial and residential developments that maintained neighborhoods while bringing them to current functionality. More importantly, all would be possible with an advanced leadership who knew Philadelphian history and was bold enough to slingshot it into a future of multiple possibilities.

“I see Philly thriving in the future,” Keola Harrington, Senior Director of Finance for the City of Philadelphia, reflected. “What New York showed is that Philadelphia very much has a global perspective, but it also has a community feel that makes it feel neighborly, while also being a big city. That is the integrity we need to keep as we grow.”

The election of the incoming mayor, Cherrelle Parker, who is the first woman head of the City, will see if her homegrown purview can progress one of the poorest major cities in the U.S. Regardless, the group prophesied hope over purple yams and ube ice cream.

| Read: Philadelphia has had 99 mayors, now they might elect 1 woman

As time ended at F.OB., people tampered down for the evening, either in their rooms or at one of the local whiskey bars welcoming foot-traffic until darkness kissed the rising morning sun. The next day was about business, boats and a Navy Yard.

This is a four-part series of shadowing a group of Philadelphia leaders who traversed to Brooklyn to see what they could learn then bring back. Currently, the City of brotherly love is in a moment of expansion and redevelopment. We have a front seat on the sculpting of a post-pandemic urban America. This series is sponsored by The Economy League of Greater Philadelphia and the Knight-Lenfest Local News Transformation Fund.