Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

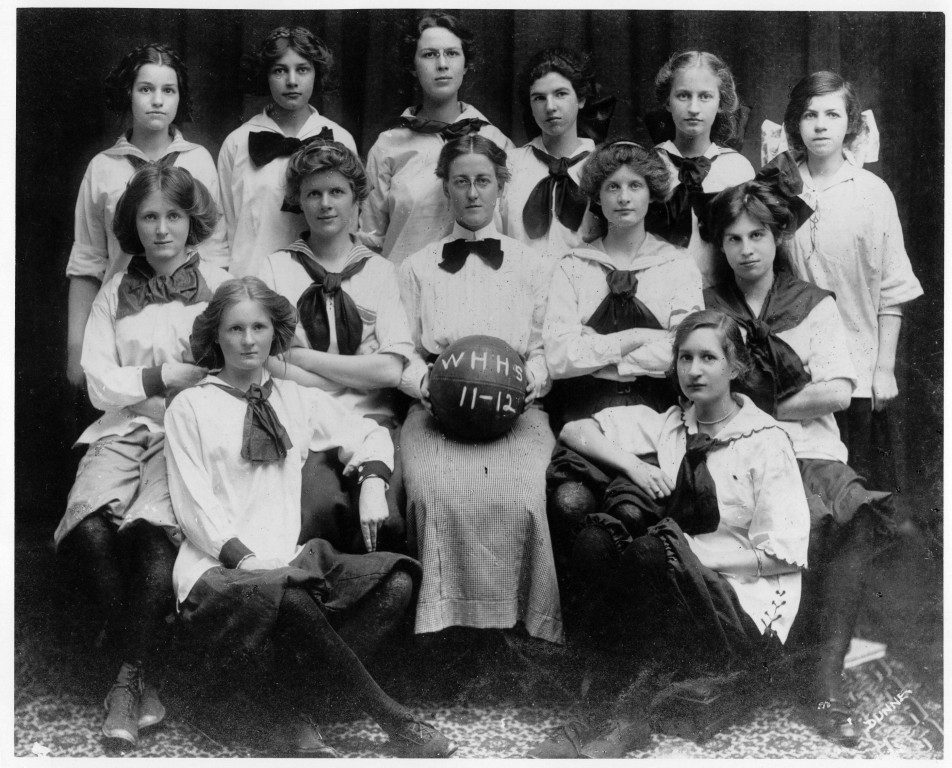

This is an iconic photo of the West Hartford High School girls’ basketball team during the 1911-1912 season, headed by Louise Day (later Louise Duffy). This was much more than a simple photograph though – this reflected the young people on the eve of the outbreak of World War I and the growth of sports during the Progressive Era in American history.

The evolution of West Hartford throughout the 1890s marked a period of steady growth, with an increasing population settling in town and working in or near it. Bonds among the young community members were strengthened through the formation of athletic and social clubs, often in collaboration with church activities. Pastimes such as polo, lawn tennis, and baseball gained popularity, reflecting a vibrant social scene.

By 1900, there was a certain energy circulating around this kind of growth. To town leaders and many residents, this was not a small farming village limited to a few generational families anymore; this was a place of limitless opportunities for the people who lived here – or if it wasn’t yet, it could be.

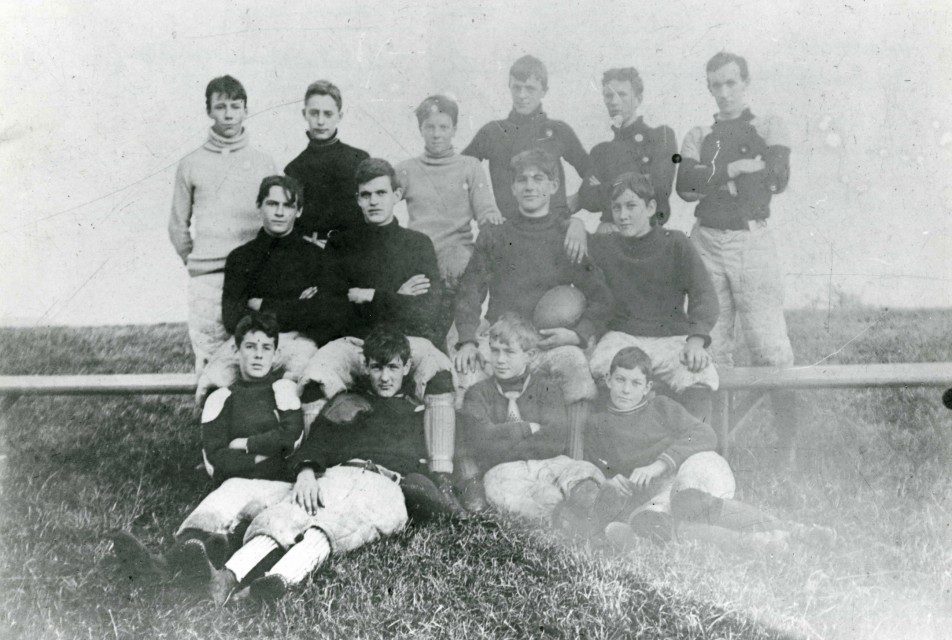

The early athletic clubs came about from a sense that the boys of the modern era had grown soft and numbed by the ruinous nature of the cities (Hartford was no different). Through athletics, they could be molded to build a new sense of community, common purpose, and physical strength – just another sign of the inertia of the day. For the men who saw themselves in the generation they were building up, the physical activity they pushed for was a way to escape from the “softness” of modern office work, bring a purity to the gritty city life next door, and perhaps redefine the concept of manliness.

It is no coincidence that American football became more popular, especially on college campuses, during this time. It had been around for decades, but the evolution of the game’s mechanics and the attitudes of the players described above made it much more violent. Boys regularly played without helmets or pads. President Theodore Roosevelt, who was one of the main advocates for the ideals above (and in today’s popular culture remains one of the “manliest” presidents), actually threatened to ban football nationally after 19 people were killed playing during the year 1905.

West Hartford football players in 1903. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Basketball, meanwhile, was invented in 1891 by a Canadian physical education teacher as a safer, indoor alternative to football. The first game took place on a court at Springfield College in Massachusetts. The first baskets were actually closed (so after scoring, the players had to get the ball out manually) and the first professional league was established in 1898 in Philadelphia.

If the danger of football was a symbol of the attitudes of men and boys during the intensity and vigor of the Progressive Era, basketball was one way that women broke away from their own histories of learning to be simple homemakers. The idea of the “New Woman” emerged, generally from middle-class white families. Girls and women started regularly bicycling, playing tennis, or participating in outdoor clubs that engaged in hiking or camping, often alongside men.

Girls in West Hartford organized small athletic clubs (like the Apple Orchard Tennis Club in 1901 by Flora Hawley) for even smaller events, but nothing exploded in popularity more than the recently invented sport of basketball. The first game took place in a barn in West Hartford on Dec. 19, 1902 and within a little over a year, it had completely taken over the town. Girls flocked to it and boys added it to the other sports they played.

By January 1904, the youth were clamoring for a court at the town hall. Within a month, athletic clubs and teams were renting out a court there. The Hartford Courant reported that March: “The basketball craze is spreading among the young people. There are now nine teams practicing, including one at Elmwood, and two girls’ teams. With dances sandwiched in, the town hall presents a lively scene night and day.”

For the next 8 years before the featured photo was taken, basketball became one of the few intense co-ed sports sponsored by the town. How could they not feel that West Hartford was the source of this energy?

A view of West Hartford Center – basketball games were played in the Town Hall located in the old Congregational Church on the right side of this photo. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Identifying all the girls in the photograph remains a work in progress and so far, I’ve only identified four of them, other than the coach Louise Day Duffy, who sits in the middle. At the top left is Alice Geer, who graduated from the high school in 1914. She moved to town at the age of 5 from Massachusetts when her father Curtis Geer was hired as a professor at the Hartford Theological Seminary and had a house built at the southeast corner of Boulevard and South Main Street. Alice played on the basketball team until her graduation. In May 1914 as a senior, she wrote an essay published in the Hartford Courant that advocated for peace in Europe as tensions bubbled, only two months before World War I broke out. She attended Mt. Holyoke College, receiving her B.A. in history in 1918. From her high school education in West Hartford until her college graduation, she was deeply impacted by the war overseas. Immediately after her marriage to her older brother’s high school friend Lincoln Kelsey in 1919, the two immediately deployed to the crumbling and partitioned Ottoman Empire to serve as relief workers in the aftermath of the war. Working with orphans in what would become Turkey, she wrote several children’s books based on her experiences. While she never came back to West Hartford, her continued participation in international relief (they were also deployed during World War II) was a product of her upbringing in the Geer family as well as the educational and trailblazing character of our town.

Alice Geer’s future sister-in-law, Jessamine Kelsey, can also be seen as a freshman in this photo standing, third from right. The younger sister of Lincoln Kelsey, she attended Mt. Holyoke as well after her graduation as valedictorian in 1915. Through the 1920s, Jessamine was involved in a variety of jobs – from saleswoman and employment office assistant at a department store in Springfield to a New York social worker. Most similarly to her time on the basketball team in West Hartford, she was director of the Springfield Girls’ Club and later involved in the Allentown, Pennsylvania Y.W.C.A. By the late 1920s, she served as field secretary with the Los Angeles League for the Hard of Hearing. One of the initiatives she reported on in 1927 was the establishment of an employment agency, surveying 110 different businesses for opportunities for the deaf. After her marriage in 1931, she started a family in Ithaca, NY (also where her brother Lincoln and sister-in-law Alice lived), but her service would have been undoubtedly felt in that community for years after.

West Hartford High School girls’ basketball team during the 1911-1912 season. Courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Standing, third from left, is the class of 1913 valedictorian, Grace Bristol. Her family moved to West Hartford when she was a baby in 1896, buying a lot at 1160 Farmington Avenue for a house set back from the road. She was the first woman valedictorian at the University of Maine in the class of 1917. Right before she graduated, her father died; she married Harold W. Coffin a year later; her brother married in the mid-1920s; and the whole family moved out of town. Grace and her husband moved to Bangor, Maine, where she taught general science in the local schools and later received a master’s degree in education from the university in 1955.

Finally, seated in the center row second from right is Alicia Wolfe, the daughter of leading figures in the area. Her father, M. Goode Wolfe, was an officer at Travelers Insurance Company; her mother Katherine was a leader in state historical activities. Together, they bought one of the houses next to the Geers on Boulevard in the early 1900s and moved to West Hartford from St. Louis after her father was hired here. Graduating from the high school in 1915, Alicia specialized in physical education at Wellesley and served as a Y.W.C.A. camp director in Trenton, NJ in 1921. She was a writer for the Christian Science Monitor before joining the faculty of Hartford Public High School in 1927. She retired in 1952 as head of the English department, meaning that there could potentially be people alive today who grew up in the city and would have known her at the high school when they went. After her retirement, she moved from West Hartford to Norwalk, continued writing, and died in 1981. Her obituary says she co-authored a book with her husband Victor, manager at the Wampanoag Country Club, about India called “Tower of Silence,” “scheduled to be published soon.” I have not been able to find any mention of this after her obituary, so it remains a bit of a mystery.

For now, there are several other unidentified girls with their own futures and stories that should be pursued. For the ones we do know, what do they tell us? They were just young children living in West Hartford when basketball broke out and infected the town. Their parents came onto the scene during the height and momentum of the Progressive Era and raised them in a town with a strong education system, just outside the ills of the city, and open to anything that would help bring more growth. The stories of these girls after their time in the high school are a reflection of that same energy – whether it was social work in New York, wartime relief, or continuing the education to the next generation, physical or not. World War I and its aftermath perhaps redirected and emboldened that sense of purpose.

Women, many from the same generation that became the early adopters of basketball, mobilized and shifted their priorities to supporting the war effort outside of the home; centralized their role in the government that would help make positive changes; and galvanized the suffrage movement that pushed for the right to vote. Obstacles remained though. The world has become more peaceful, but war and violence continue – sometimes from the same attitudes that were prevalent back then.

The predominance of middle-class white women in the Progressive movement meant that immigrant and black women continued to lag behind. Social bonds remain frayed, local communities are often fragmented, and economic inequality shows no sign of discernible improvement. The re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s (of which many women were active participants or simply complicit), the difficulties of the Great Depression, and the mobilization required by women during World War II meant that there was plenty of work to do. In many respects, there is much to do today. But if they can play basketball, so can we.

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.