“During the rainy season, the storms would be so bad and the mud would be so thick that it was difficult to get out,” she said. “So from ‘Sal si puede,’ we went to ‘Sí se puede.’”

“Si se puede” translates to “Yes, we can,” and it’s a slogan credited to Dolores Huerta, who co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (later called the United Farm Workers union) with César Chávez. In the decades since, the slogan has been adopted by activists all over the United States.

Alvarado remembers meetings Chávez held in her garage. “We saw our movement beginning to pick up steam and presence with César Chávez, CSO and the farmworker call for action as well. So today, when we talk about César Chávez, I think we do it with nostalgia for the man. But [also]for the time that we experienced with him. There was so much excitement. There was so much energy. There was so much goodwill.”

“Chávez didn’t come out of nowhere,” said Margo McBane of San José State. “He came out of the shoulders of all these other people working for labor and community civil rights.”

“In San José, in Los Angeles, and in other urban communities, we, the Mexican American people, were dominated by a majority that was Anglo,” Chávez said in a Commonwealth Club address in 1984. “I began to realize that the only answer, the only hope, was in organizing.”

As the 1970s wore on, the Chicano Movement made steady gains: improving conditions for migrant farmworkers, establishing Chicano studies in California schools and universities, and getting Mexican Americans elected.

But Alvarado said it was slow going “because we were not allowed to be part of the establishment, of the rulers of the time. We had to form our own institutions and we had to form our own protest organizations.”

Alvarado became the president of the Santa Clara County chapter of the Mexican American Political Association. She got into commission and committee work where she and other members learned the rules about how to confront, petition, and be a voice in government.

Alvarado helped push for San José to switch from at-large to district elections, making it much easier for political newcomers to win elections, especially in under-represented areas. In 1980, she ran to represent her district, and won. That’s when she became the first Latina member of the San José City Council.

Over her roughly 30-year political career, Alvarado focused on health insurance and literacy programs for children; expanding access to public green space; and starting the fight to close down a small airport in East San José because of the noise and air pollution. She played a key role in launching the Mexican Heritage Plaza, and getting San José’s premier downtown park, known for hosting parties and protests, renamed the Plaza de César Chávez.

But these are the kinds of battles against systemic racism that take years to wage, the kinds of wins that typically fade fast from public view.

“She’s saying, ‘My community deserves a seat at the table. I deserve a seat at the table,’” Santa Clara County Supervisor Cindy Chavez said of Alvarado. Chavez got involved with local politics in the late 1980s, in large part, she says, because of Alvarado’s example.

Generations of Latinas in the South Bay have sought public office in Alvarado’s wake, often seeking her endorsement. Chavez says she feels a sense of responsibility to finish what Alvarado started, on behalf of a community that has long felt unseen and unheard.

Historian Suzanne Guerra says understanding the impact of Mexican Americans on this region deepens our connection to history.

“You know, when I was a kid, I learned my American history, my California history like everybody else, but folks like me and my family, we disappeared,” she said.

Google it. This history is hard to find unless you already know what you’re looking for. And even then, “We’re still considered ‘other history,’ not American history. When the truth is, American history is everyone’s history,” Guerra said.

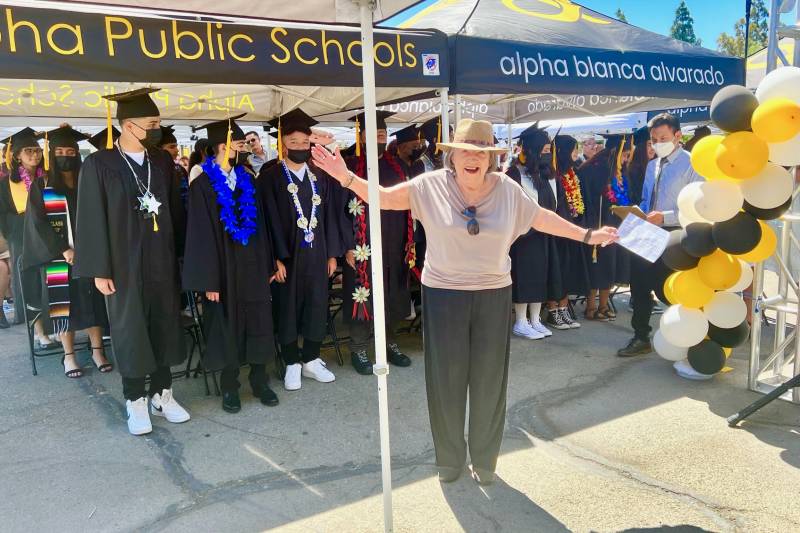

A few years ago, Alvarado got a special thrill when a local elementary school was named after her: the Alpha Blanca Alvarado School in East San José. There’s also a community health center named after her.

Alvarado says she hopes younger generations of Latino activists take strength from her example. Many of the issues she fought for including health care, representation and housing are still fights today in San José. She says it’s time for the youngsters to start making their mark.