This report was co-authored by Education Analyst Ashley Young and Senior Analyst, Worker Justice & Criminal Legal Systems, Ray Khalfani.

Executive Summary

The education-to-workforce bridge is one of many critical pathways to economic security for Georgians. However, policy decisions can destabilize this bridge and reinforce broader structural inequities, including occupational segregation and student loan debt. To address the structural inequities that delay and derail Georgians’ opportunities to reach economic security, state lawmakers should:

- Prioritize state investments to close Georgia’s widespread student-to-counselor access gaps.

- Promote successful college completion and alleviate the burden of student loan debt by establishing a state need-based financial aid program. This program can be funded by various sources, such as general funds and the education lottery, and can offer financial assistance to Georgians pursuing four-year degrees, short-term certifications and those taking unpaid internships. By doing so, higher education can become more accessible and affordable for all.

- Improve job quality as a bridge to workforce training access, expand workforce training access to global talent and include racial equity-centered components within Georgia’s State Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Plan that tracks and addresses digital skills gaps and monitors workforce training program-level outcomes.

Introduction

This report highlights the economic security barriers within Georgia’s higher education and workforce systems and the ways they perpetuate occupational segregation.[1] The analysis also underscores the role that job quality plays across both systems in securing future bridges for economically disadvantaged Georgians. Although work-based income is not appropriate for every Georgian, state lawmakers have a duty to provide an equitable means for all who seek employment or job skill development to obtain better wages, job mobility, stability and long-term pathways to wealth-building.

Occupational segregation occurs when people, particularly women and people of color, are relegated to certain industries or sectors – often those that pay low wages. Occupational segregation is a collection of structural practices within educational, workforce and other systems that reinforce inequitable workforce patterns. For example, biased academic practices funnel students into credentials or fields of study according to their race, ethnicity, immigrant status or gender. Other practices make post-secondary attainment unaffordable for those at or below the economic margins, which reproduce inequities that can cut across the demographics listed above. Occupational segregation doesn’t just bar select individuals from pathways to quality jobs, it ultimately harms everyone. Occupational segregation stifles the state’s labor force adaptability and weakens productivity across Georgia’s broader economy.

This report also highlights the importance of addressing specific structural barriers that fail to prioritize worker needs or racially-equitable training outcomes by emphasizing three critical bridges: investing in quality high school student counseling, expanding access to post-secondary education and workforce training and improving the public workforce system.[2]

Georgia has already begun to make positive progress as state policymakers have taken recent steps to reinforce the education-to-workforce bridge. Those steps include boosting state investments incentivizing businesses to expand registered apprenticeships, expanding college completion grants to improve college affordability, prioritizing student-parents for state child care subsidies, initiating steps to reduce four-year degree requirements for state public sector jobs and expanding broadband internet access to bridge the digital divide across education and workforce systems throughout the state. However, these changes fall short of advancing economic opportunity for all Georgians. Additional equity-centered state policies and investments are needed to improve students’ and skill-building workers’ return on investment and solve racial disparities in employment that persist despite a growing economy.

Breaking Barriers

Barrier: Limited Access to Quality Counseling – Guiding Pathways to Success

Post-secondary education is one of the most promising pathways for Georgians to secure quality jobs. However, this opportunity is often missed due to limited access to quality counseling in public education. Young people are unsure how to attain post-secondary degrees or credentials, which makes it necessary to improve the quality of counseling services available to them. Comprehensive secondary counseling is critical to supporting students’ transition from high school to higher education or the workforce. School systems with manageable student-to-counselor ratios maximize access to quality counseling, which is indispensable to a student’s post-secondary success.

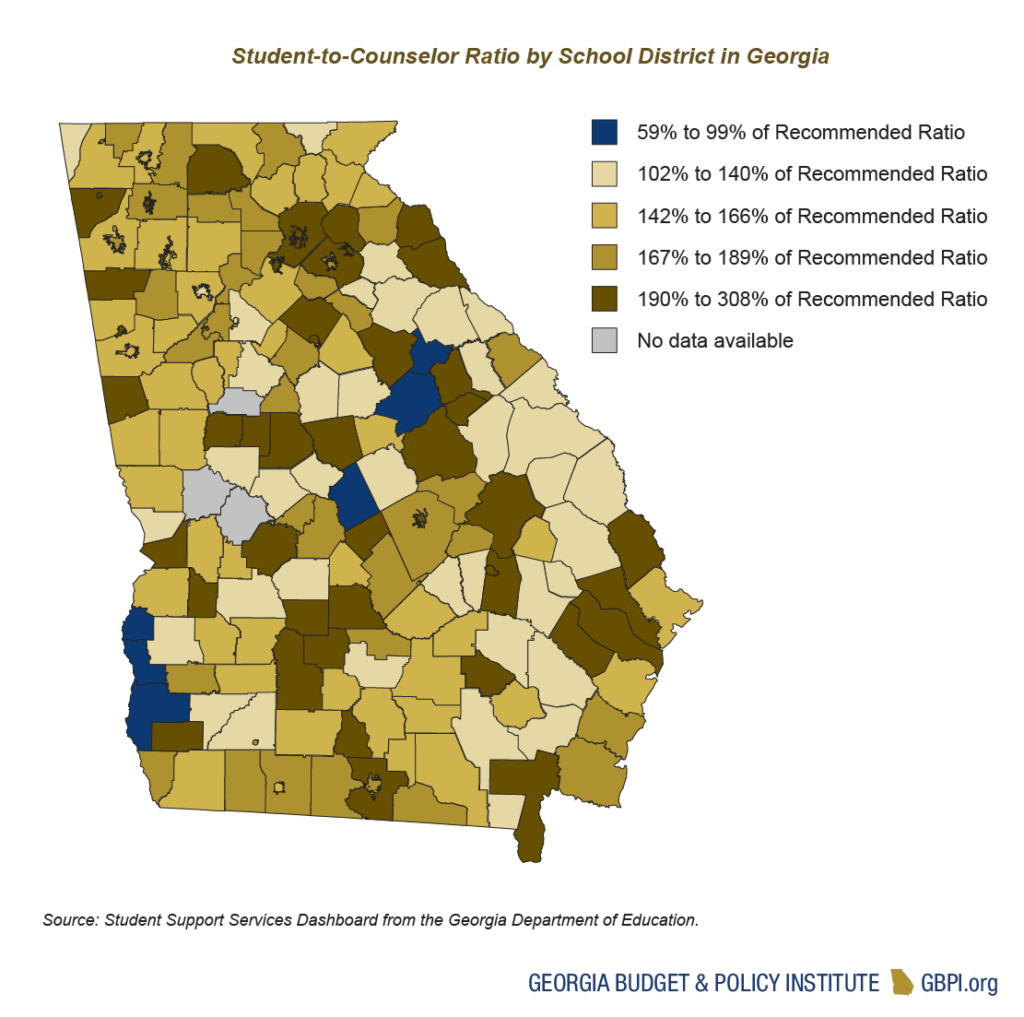

The American School Counselor Association (ASCA) suggests a 250:1 student-to-counselor ratio.[3] However, data on Georgia’s student-to-counselor ratio demonstrate significant quality counseling barriers, where there are too many students for too few counselors. In the 2021-2022 academic year, ASCA reported that Georgia’s average public high school student-to-counselor ratio was 411:1, slightly above the national average of 408:1.[4] As a result, poor student counseling access in Georgia likely mirrors or exceeds national trends, where almost 1 in 5 students do not have access to a school counselor.[5]

While making post-secondary education more accessible and affordable can address occupational segregation barriers that occur further downstream, improving quality counseling access in high schools can foster community buy-in upstream and help to counter rural and historically underserved communities’ preconceived notions, stereotypes and skepticism about post-secondary education.[6]

Desiree, Black Woman Resident and Georgia High School & College Graduate

Comments on college affordability and effect of student debt:

“I went to school in one of the metro Atlanta counties. I didn’t have a college counselor showing me…like, hey, these are your options. I think one of the major resources that I would’ve loved to have had was someone walking me through the steps of—this is what having a scholarship would be. Not having a detailed education or just insight to what student loans would do to the future prospects of my socioeconomic status…I think it was kind of a catch-22.”

– Desiree, Black Woman Resident and Georgia High School & College Graduate

Research shows a lower student-to-counselor ratio, which equates to smaller counselor caseloads, correlates to fewer discipline incidents, improved grade point averages, better graduation rates and yields higher career readiness competence.[7] Large caseloads not only present barriers for students to access a counselor but are also detrimental to school counselors’ job effectiveness.[8]

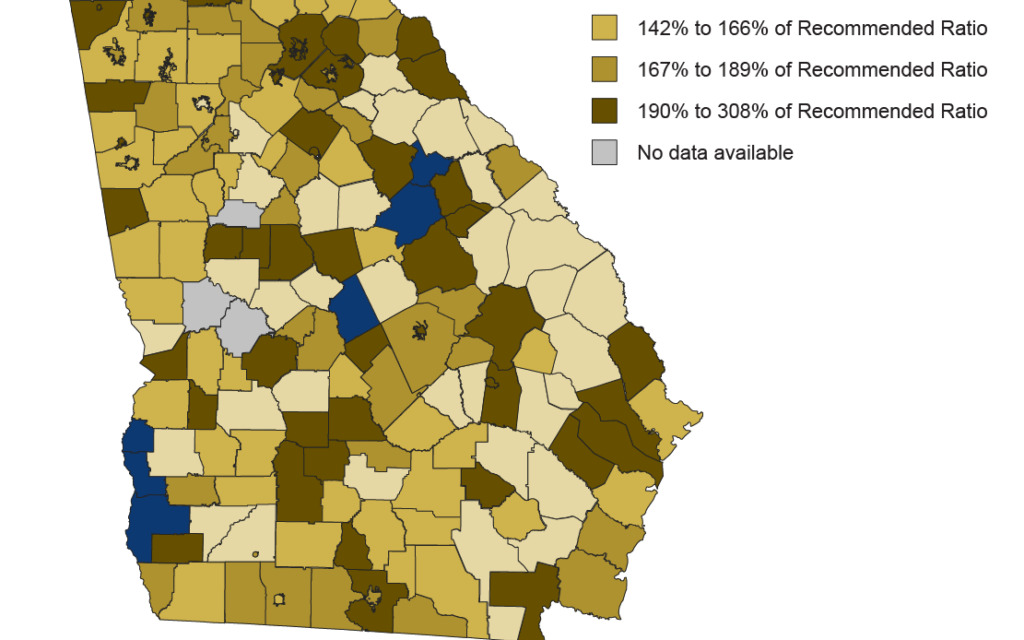

High caseloads increase counselors’ stress and anxiety, limit their availability for post-secondary planning and hinder their ability to schedule courses, provide social-emotional support and administer tests. Only seven out of 179 Georgia school districts meet the recommended 250-to-1 student-to-counselor ratio, highlighting widespread counselor access challenges (see map below).

Students within Black and Latinx households experiencing economic inequity may have fewer informal opportunities for economic advancement due to lack of family relationships and social networks.[9] This dynamic may signal greater reliance on school counselors to identify and inform students of suitable four-year degree options or short-term opportunities to earn quality non-degree credentials that position them for quality jobs and minimal student debt. Without quality counseling access, students experiencing economic hardship face greater risks of making uninformed choices that can combine with inequitable systemic factors to bar them from quality jobs.[10]

Georgia’s poor student-to-counselor ratio also contributes to the lack of interest in middle-skill jobs because of outdated societal stigmas and a lack of awareness of the degree and non-degree credentials, particularly digital skill credentials, necessary to pursue those jobs.

Barrier: Post-secondary Affordability – A Case for Need-Based Financial Aid

In a recent GBPI panel discussion, Dr. Timothy Renick of Georgia State University (GSU) highlighted the urgency for a statewide need-based financial aid program:

“Prior to GSU adding its own limited form of need-based aid, I got to see a very disturbing dichotomy where students who were equally talented included some who graduated, and others who would drop out with no degree, and often with student debt. The distinction wasn’t drive, determination or ability: it was in many cases financial resources. Among 75,000 students in an 8-year longitudinal study, the graduation rates among students who never had to stop for a financial reason was over 70%, while the rate for students who had to stop for a financial reason was under 20%.”[11]

GSU has led both the state and nation in college retention grant implementation and research. Understanding how to best identify and support students who require need-based financial aid is integral to post-secondary affordability. Despite GSU’s research, Georgia remains one of two states that do not offer comprehensive need-based financial aid to support students with post-secondary costs, maintaining a major barrier to student success. Decades of failure to recognize the value of need-based financial aid has created difficulties for Georgia students, delaying their degree completion while deterring others from pursuing post-secondary education due to high costs. Meanwhile, an equity-oriented policy approach has been used in other states, in combination with student support services, to increase educational attainment.[12]

Need-based and non-need-based financial aid are aimed at supporting students who struggle to meet the financial demands of higher education. Non-need-based aid programs focused on academic performance, like Georgia’s HOPE and Zell Miller Scholarships, are commonly referred to as “merit-based aid” and are quite competitive. These scholarships are geared toward retaining students in-state and have been found to expand students’ power to select the college of their choice rather than improve educational outcomes.

Prioritizing higher education access through merit-based aid perpetuates Georgia’s longstanding structural inequities, which fail to increase educational attainment broadly and limit institutional options for students who are financially on track to attend college.[13]

Supporting economically disadvantaged students is vital to unlocking their potential and preventing occupational segregation in Georgia. This is especially important in the digital age, where demand for digital skills is on the rise. These skills include foundational skills such as email, simple spreadsheets, data entry or timecard software, as well as industry-specific capacities, such as bookkeeping with OuickBooks.[14]

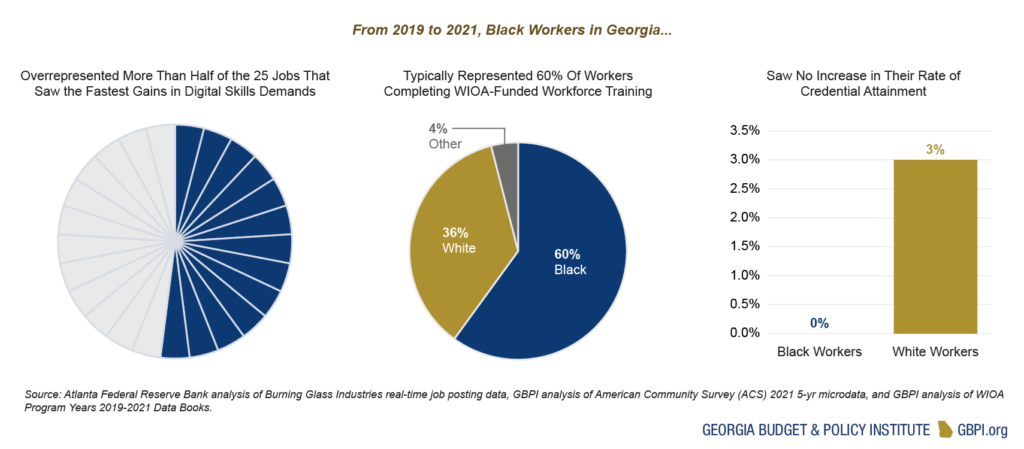

Making post-secondary education more affordable will expand access to digital skill-building. Bridging Georgia workers to education and training in digital skills can address workforce equity gaps, especially for Black workers who are overrepresented in 13 of Georgia’s top 25 occupations with rising digital skills demand. Without need-based aid, the bridge between higher education and jobs with livable pay will keep getting narrower, and its utility in bridging economic security will become more limited, especially with inflation eating away at buying power. In 2021, a job with just one digital skill requirement had an hourly wage of over $21, which is almost 30% more than typical jobs in Georgia that don’t require digital skills. Further, as of 2021, 90% of Georgia job postings required “definitely digital” or “likely digital skills.”[15]

Barrier: A Public Workforce System Framework that Reproduces Inequity

Systemic barriers to quality jobs are also reinforced by Georgia’s public workforce training system, which implements state-specific workforce training policies under a broad federal framework known as the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA). Operating primarily alongside Georgia’s traditional four-year colleges and universities, Georgia’s WIOA-funded public workforce system comprises adult basic education and GED programs, apprenticeships, nonprofit organizations, community colleges and employers that provide job training. Largely administered by the US Department of Labor, US Department of Education and Health and Human Services, WIOA is “designed to help job seekers access employment, education, training, and support services to succeed in the labor market and to match employers with the skilled workers they need to compete in the global economy.”[16]

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic recovery, workers seeking support from Georgia’s public workforce training system have met a system that reinforces economic exclusion and poverty as demonstrated by data and design. Despite the state’s long-term workforce gaps, WIOA-funded skills training remains mostly out of reach for Georgia immigrants without work authorization, including those whose authorizations remain pending because of delayed processing. Even with their eligibility limited to WIOA Title II Adult Education and Literacy training, data suggests this training only reaches a fraction of Georgia’s immigrant population. Nationwide, immigrants make up nearly 90% of individuals with Limited English Proficiency (LEP), and Georgia’s LEP population provides a window into immigrant workforce training gaps.[17]

Approximately 429,000 prime working-age adults in Georgia have LEP.[18] Across the state, foreign-born workers represent 16% of the prime-age workforce but make up 30% of Georgia’s workforce without a high school diploma or equivalent. This means that nearly 159,000 foreign-born workers in Georgia have limited education. However, only 15,978 Georgians with LEP completed Adult Education and Literacy training funded under the Title II WIOA program in 2021-2022. Limited access to training could be partially attributed to the low-quality and unstable jobs in which immigrants tend to work. This dynamic likely reinforces a vicious cycle in which an immigrant becomes trapped in a low-quality job due to lack of training, but there is also a lack of training opportunity inherent in the low-quality jobs itself. This lack of training opportunities undermines efforts to provide English language support and basic academic and vocational skills, which are essential for pairing immigrant workers with WIOA Title I workforce training programs. This training could also play a major role in filling digital skills gaps.

Despite Georgia workers quitting their jobs at higher rates than the national average, Georgia’s workforce policies have failed to provide adequate upskilling opportunities for workers.[19] Unfortunately, the state’s workforce system does not prioritize the needs of workers and fails to meaningfully expand access to workforce training. While state policymakers cannot override federal WIOA policy to increase worker representation in state and local workforce development boards, Georgia continues to forfeit opportunities to improve job quality and workforce training access. This includes barring local governments from regulating fair job scheduling, providing access to overtime and setting livable minimum wages. These restrictions on local government perpetuate job instability that heightens training access barriers for low-wage workers. Georgia is also one of a few states that does not invest in incumbent worker training that helps employers train and retain full-time employees by providing skills upgrades, inhibiting employers from boosting job quality and retaining workers.[20] As a result, Georgia’s small businesses are more vulnerable to experiencing high turnover costs as workers leave for other jobs offering training and advancement opportunities.

Furthermore, Georgia’s WIOA state plan excludes race-conscious workforce outcome goals despite inequitable training, employment and wage results that perpetuate occupational segregation. WIOA training outcome data among Black and white workers in Georgia demonstrate a problematic reproduction of racial inequities in the workforce. Between 2019 and 2021, Black workers enrolled in WIOA training realized an 87% increase in measurable skills gains but experienced no increase in credential attainment.[21] In comparison, white workers realized a 66% increase in measurable skills and a 3% increase in credential attainment.[22] These disparate credentialing outcomes, paired with Black workers who exited WIOA training and found jobs with minimal increases in median pay compared to their white counterparts, demonstrate a need for an equity focus on skills attainment, particularly around digital skills, and on credentialing outcomes. A targeted focus on digital skills gaps is necessary to improve equity, as Black workers are overrepresented in most jobs in Georgia that had the fastest rising digital skills demands from 2019 to 2021.[23]

WIOA training outcome data only provides aggregate trends on measurable skills growth. This aggregate is a sum of growth across both “hard skills” like typing or the ability to use spreadsheets, and “soft skills” that are typically defined by employers as interpersonal skills or personality characteristics, such as “works well within teams.” However, research on a segment of training programs that are often WIOA-funded and serve a disproportionate share of Black workers, found that Black participants were largely funneled into training and jobs that overemphasized “soft” skills and offered minimal pay.[24] Soft skills have often been found to be highly subjective, prone to racial bias and a perpetuating factor in systemic barriers to quality employment for Black Georgians.[25] Without WIOA performance metrics that specifically assess digital hard skills gains, policymakers remain without equity tools to better reach workers experiencing the greatest workforce barriers.

Building Bridges

Bridge: Quality School Counseling – Enhancing Student Preparedness

Policy Recommendation: Georgia legislators should increase funding for student support services to lower the student-to-counselor ratio and recruit and retain college and career preparation professionals to assist students after graduation. In districts with a high population of students of color and students who are economically disadvantaged, lawmakers have the most room for improvement.

When students have quality guidance and a strategic post-secondary plan, it can increase their likelihood of success. Without these preparation measures, students may encounter unexpected roadblocks that can alter their life’s trajectory. All students in Georgia deserve equitable and adequate access to a school counselor so that they have the tools to navigate life after high school.

Investing in resources to hire more school counselors is crucial for promoting equity in education. Financially marginalized students and those attending low-income schools often struggle academically, and counselors can play a vital role in supporting them.

This is especially true for students of color, first-generation college students and students from families with low wealth. Unfortunately, the economic consequences of low educational achievement can impact these students well into adulthood. Research shows that it costs districts significantly more to educate a student in poverty than one who is not, underscoring the need for policy approaches, like an opportunity weight, to help support students with low incomes.[26]

In school districts with high poverty rates, counselors often take on multiple responsibilities. Unfortunately, this can lead to students not receiving the individualized attention they need to make important decisions about their future. Without the guidance of a counselor, students may not fully understand the consequences of their choices, like taking out student loans to pay for college. It’s important that every student has access to the resources they need to make informed decisions and achieve their goals.

Desiree, Black Woman Resident and Georgia High School & College Graduate

Comments on value of providing information in high school years around student debt and financial aid options:

Increasing funding for additional school counselors would allow more time to support students on the nuances of post-secondary education or job preparation programs so that they can choose the most appropriate plan. To close this funding gap equitably, Georgia must increase resources and allocate them strategically, accounting for the systemic reasons why such gaps exist, such as past racial discrimination in Georgia’s Black Belt.[27] As lawmakers consider investing in K-12 education, they must understand the historic and racialized context of their decisions and prioritize strengthening counseling resources to build a stronger bridge to higher education for all students.

Bridge: Expanding Access to Post-secondary Education & Workforce Training

Policy Recommendation: Georgia lawmakers should consider multiple funding sources, including the general fund and state lottery reserves, to fully fund a comprehensive need-based financial aid program that mitigates the harms caused by decades of discrimination in higher education and counterbalances racial inequities in both the HOPE and Zell Miller Scholarships.[28]

Policy Recommendation: As part of a comprehensive approach to addressing post-secondary access gaps and segregated tracks of study, lawmakers should provide need-based aid funding eligibility for unpaid internships and quality short-term credential programs, including digital skills training.

Policy Recommendation: To expand on recent efforts to reduce public and private sector four-year degree requirements, the state should develop a quality assurance framework around need-based aid to ensure that degree and credential seekers gain the skills and competencies needed to find employment with opportunities for mobility, that employers attract Georgia workers who meet workforce needs, and that employers and lawmakers collect, use and share transparent racial equity information about outcomes associated with the credentials in which they are investing.

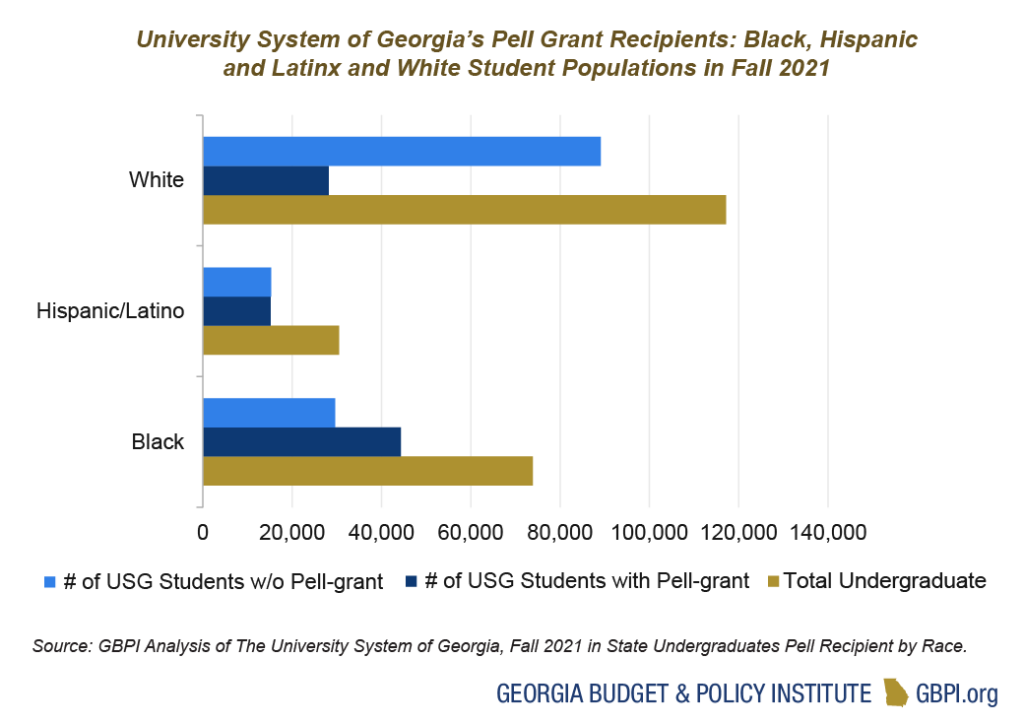

College affordability is critical for advancing racial equity in Georgia, as 40% of Georgia undergraduate students received the Pell Grant in the 2020-2021 academic year compared to 32% nationally.[29] A need-based financial aid program to ensure that all students have access to post-secondary education is a significant step to improving Latinx and Black students’ economic security. Furthermore, need-based aid addresses equity gaps across race and gender, as the student debt crisis explicitly harms Black women and Georgia ranks third nationally for student loan debt per borrower.[30]

How the Student Loan Debt Crisis Harms Black Women

Nationally, Black women bear the greatest burden of the student loan debt crisis. Black women carry the most debt of any racial/ethnic group, totaling on average $38,800 for undergraduate student loan debt and $58,252 for graduate student debt in the United States. This plight worsens due to occupational segregation and gender and racial pay gaps. Statistically, Black women must attain a bachelor’s degree just to earn as much as white men who have some college but no degree. Black women borrowers are forced to borrow the highest amount of student loans to attend college and then suffer from wage discrimination during the repayment process. Georgia is third in the nation for student loan debt per borrower, behind the District of Columbia and Maryland, respectively.

Federal Pell Grant data illustrates that Black and Latinx students require greater financial support to attend college. In the fall of 2021, 60% of the 73,901 Black students and 50% of the 30,477 Hispanic/Latino students in the University System of Georgia (USG) were Pell grant recipients, compared to only 24% of white students.

Beyond expanding college affordability for four-year degree seekers, need-based aid can be a tool to expand access to quality short-term credentials that include digital skills training, particularly in community colleges that can rapidly adapt to the pace of industry skill demands.[31] Need-based aid could reduce financial barriers to unpaid internships and other non-tuition expenses that can dissuade students of color from pursuing certain academic tracks. Another option is to braid need-based aid funding with federal infrastructure dollars to help facilitate short-term training across the state for infrastructure jobs related to Georgia’s broadband expansion efforts.

One funding source for state need-based aid is the education lottery, through which HOPE and Zell Miller Scholarships are resourced. The education lottery currently has $1.9 billion in overall reserves.[32] By state law, the education lottery reserve must have at least 50% of the prior year’s proceeds in the shortfall reserve, which totaled $772 million in 2022. The state’s education lottery has $1.1 billion in unrestricted reserves, which could be used to create a comprehensive need-based aid program.

Once funding sources have been identified, research suggests that a state-sponsored comprehensive need-based financial program should have a framework in place for distributing need-based aid grants.[33] In most states, colleges and universities are responsible for awarding grants, which allows for flexibility in determining the size of the award. This is important given the varying sizes of institutions, cost of attendance and unique financial circumstances of individual students.

Rather than disbursing need-based aid grants through a central state agency, schools can distribute funds on a sliding scale to meet the needs of each student more equitably. Basing the award on a student’s expected family contribution (EFC) and the number of completed credit hours would help an institution equitably determine a student’s award amount to best suit their financial needs.[34]

Overall, state need-based aid is a critical piece of the puzzle in addressing wage inequities and helping bridge the gap to economic security.

Bridge: Center Workers Within Georgia’s WIOA Policy Framework

Policy Recommendation: Improve job quality to expand worker access to WIOA job training programs. This includes allowing local governments to regulate fair scheduling practices and access to overtime, increasing the state minimum wage and indexing it to economic growth and prioritizing investments toward a state-level Incumbent Worker Training fund.

Policy Recommendation: Attract and expand more global talent, including Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients, into Georgia’s workforce by expanding workforce training eligibility to a wider pool of Georgia immigrants. To accomplish this, state policymakers should consider braiding WIOA’s Title I Adult Education funds together with Title II Literacy Skills training and eliminating unnecessary barriers to professional and occupational licenses.

Policy Recommendation: Invest in a comprehensive, racial equity-centered plan to track and address digital skills gaps and track workforce training program-level outcomes under WIOA.

As part of more inclusive public workforce training policies that center workers and racial equity, Georgia policymakers have an opportunity to improve the conditions of employment – including training, hours and work assignments – that can improve all workers’ pathways to quality, well-paying jobs with rising digital skills demands. With a job quit rate that consistently outpaces the national average, state policies to improve job quality are the path forward to attract and retain workers who seek job growth opportunities, career advancement and increased earnings. Providing state-level incumbent worker training funds can also supplement existing but limited WIOA funding for incumbent worker training. Incumbent worker training helps employers train and retain full-time employees by providing skills upgrades. These investments should be relatively easy to access by employers, prioritized to upskill frontline workers and provided based on accountability metrics that capture digital skills learning gains and ensure workers receive equitable pay increases following training. These measures would serve as essential steps toward prioritizing workers’ desires and needs for greater career mobility, help reduce worker attrition across the state and allow more Georgia businesses to become “employers of choice.”[35]

Furthermore, expanding WIOA eligibility for global workforce talent in Georgia can help mitigate long-term labor shortage trends. Georgia already has a promising training model for integrating basic skills education with workforce training, known as I-BEST, which could be utilized to train global talent in need of both Title I WIOA workforce training and Title II Adult Education training. Georgia lawmakers can also help expand the state’s workforce training opportunities by removing unnecessary barriers to state professional and occupational licensing. For example, lawmakers can make it easier for immigrants to access transportation to job training sites by allowing them to obtain driver’s licenses regardless of immigration status. Additionally, they can ease the burden of demonstrating identity during the occupational license application process by accepting Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITIN) to serve as an alternative form of identification to a Social Security number.[36]

Last, Georgia’s state workforce development board should include race-conscious training outcome goals in its WIOA State Plan, as part of targeted efforts to end inequitable credential attainment, wage growth and digital skills gaps across race. Georgia can only eliminate workforce training outcome gaps and create greater inclusivity by embedding an anti-racist mission as part of the core of its workforce system.

Conclusion

To address the issue of occupational segregation, state lawmakers should start by addressing Georgia’s education-to-workforce pipeline. One way to do this is by ensuring that all high school students have access to support systems that can support their post-secondary paths, regardless of whether they live in rural or underserved areas.[37] Additionally, implementing financial aid and other mechanisms could provide students with alternative options that may reduce their reliance on student debt and help build intergenerational wealth. A need-based aid system could also help mitigate Georgia’s student debt crisis while providing life-changing bridges to post-secondary completion and future workforce success. Finally, a worker-centered WOIA framework that is inclusive of Black, Brown and immigrant WIOA trainees, and tracks their growth in digital skills attainment, could help to reverse harmful training outcome trends and support individuals as they navigate the evolving job needs of high-demand industries.

As GBPI continues to provide policy solutions that build bridges over barriers within Georgia’s education-to-workforce pipeline, the next publication in this report series will lean into the intersecting and compounding barriers of inadequate child care policies. The implementation of such policies only exacerbates existing occupational segregation, leading to more unfair outcomes for student and working parents.

As state lawmakers consider additional policy shifts to create a more inclusive path to economic security, strengthening Georgia’s child care safety net will protect additional Georgians from financial hardships that can derail them from a prosperous education-to-workforce pipeline.

Endnotes

[1] Zhavoronkova, M., Khattar, R., & Brady, M. (2022). Occupational segregation in America. Center for American Progress. Retrieved August 9, 2023 from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/occupational-segregation-in-america/

[2] Camardelle, A. (2021 October). Principles to support Black workers in the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. Retrieved August 23, 2023 from https://jointcenter.org/principles-to-support-black-workers-in-the-workforce-innovation-and-opportunity-act/

[3] American School Counselor Association. (2004). Student-to-school counselor ratio 2003-2004. American School Counselor Association.

[4] School Counselor Roles & Ratios – American School Counselor Association (ASCA). (n.d.). https://www.schoolcounselor.org/About-School-Counseling/School-Counselor-Roles-Ratios

[5] The Education Trust. (2019). School counselors matter. https://s3-us-east-2.amazonaws.com/edtrustmain/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/30161630/ School-Counselors_2019_V7.pdf

[6] Sanchez, O. (2023 ,May 18). J-O-B degree for rural Students. The Hechinger Report. Retrieved August 23, 2023, from https://hechingerreport.org/newsletter/j-o-b-degree-for-rural-students/

[7] Lapan, R., Gysbers, N., Stanley, B., & Pierce, M. (2012). Missouri professional school counselors: Ratios matter, especially in high-poverty Schools. Professional School Counseling, 16(2), 108–116. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2156759X0001600207

[8] Mullen, P. R., Chae, N., Backer, A., & Niles, J. (2021). School counselor burnout, job stress, and job satisfaction by student caseload. NASSP Bulletin, 105(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192636521999828

[9] Wilson, V., & Darity Jr., W. (2022 March 25). Understanding Black-white disparities in labor market outcomes requires models that account for persistent discrimination and unequal bargaining power. Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved August 23, 2023 from https://www.epi.org/unequalpower/publications/understanding-black-white-disparities-in-labor-market-outcomes/

[10] Reichlin Cruse, L., Stiddard, J., Taylor, R., & LaPrad, J. (2023, July 19). The non-degree credential quality imperative. National Skills Coalition. Retrieved August 23, 2023 from https://nationalskillscoalition.org/resource/publications/the-non-degree-credential-quality-imperative/

[11] Renick, T. (2023, August 17). Exploring Georgia’s lack of comprehensive need-based aid [Conference panel]. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute Virtual Event, Atlanta, GA.

[12] Cummings, et al. (2021, May). Investigating the impacts of state higher education appropriations and financial aid. State Higher Education Executive Officers Organization. https://sheeo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/SHEEO_ImpactAppropationsFinancialAid.pdf (citing Angrist et al., 2020; Carruthers & Fox, 2016; Gurantz, 2018; Miller et al., 2020; Page et al., 2019b).

[13] Cummings et al. (2021, May). Investigating the impacts of state higher education appropriations and financial aid. State Higher Education Executive Officers Organization. https://sheeo.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/SHEEO_ImpactAppropationsFinancialAid.pdf

[14] Ibid.

[15] Bergson-Shilcock, A., Taylor, R., & Hodge, N. (February 2023). Closing the digital divide: The payoff for workers, business, and the economy. National Skills Coalition. Retrieved August 9, 2023 from https://nationalskillscoalition.org/resource/publications/closing-the-digital-skill-divide/

[16] United States Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration. Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. https://www.dol.gov/agencies/eta/wioa

[17] Wilson, J. (2014, September). Investing in English Skills: The Limited English Proficient Workforce in U.S. Metropolitan Areas. Brookings Institution. Retrieved on September 5, 2023 from https:// www.brookings.edu/articles/investing-in-english-skills-the-limited-english-proficient-workforce-in-u-s-metropolitan-areas/

[18] GBPI analysis of IPUMS American Community Survey 2017-2021 microdata, from the University of Minnesota.

[19] GBPI analysis of state-level Bureau of Labor Statistics monthly JOLTS reports from 2022.

[20] Bergson-Shilcock, A. (2020, August 18). Funding resilience. National Skills Coalition. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://nationalskillscoalition.org/resourrece/publications/funding-resilience/

[21] GBPI analysis of WIOA data books from Program Years 2019 to 2021. Analysis of Table 11-28: Outcomes by race, among adults leaving WIOA training programs.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank analysis of Burning Glass Industries 2019 to 2021 job posting data in Georgia.

[24] Marketplace. (2023, March 23). Chapter 1: The dream—Whom does welfare-to-work really work for? Retrieved September 8, 2023 from https://www.marketplace.org/shows/the-uncertain-hour/chapter-1-the-dream/

[25] Mehta, S. (2022, April 19). Updating WIOA to empower workers and create shared prosperity. Center for Law and Social Policy. Retrieved August 23, 2023 from https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/updating-wioa-to-empower-workers-and-create-shared-prosperity/

[26] Owens, S. (2023, January 26). State of education funding (2023): Opportunity is knocking. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/state-of-education-funding-2023-opportunity-is-knocking/

[27] Owens, S. (2019, October 16). Education in Georgia’s Black Belt: Policy solutions to help overcome a history of exclusion. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/education-in-georgias-black-belt/

[28] Lee, J. (2022, February 23). The need for need-based aid. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/the-need-for-need-based-aid/

[29] National Center for Education Statistics. (2021). Percent of undergraduate students receiving Pell grants. https://shorturl.at/eotvK

[30] Hanson, M. (2022, April 3). Student Loan Debt by State [2023]: Average + Total Debt. Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-by-state; Jackson, V., & Williams, B. (2022, April). How Black women experience student debt. The Education Trust. https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/How-Black-Women-Experience-Student-Debt-April-2022.pdf

[31] Jacoby, T. (2021 September). The indispensable institution: Taking the measure of community college workforce education. Opportunity America. Retrieved August 24, 2023, from https://opportunityamericaonline.org/ccstudy/

[32] State Accounting Office. (2022). 2022 report of Georgia revenues and reserves. https://sao.georgia.gov/document/document/22grrr092322securedpdf–UNPUBLISHED-document–DO-NOT-SHARE-this-URL–/download

[33] Reichlin Cruse, L., Stiddard, J., Taylor, R., & LaPrad, J. (2023, July 19). The Non-degree credential quality imperative. National Skills Coalition. Retrieved August 23, 2023 from https://nationalskillscoalition.org/resource/publications/the-non-degree-credential-quality-imperative/

[34] Lee, J. (2021). A need-based financial aid program for Georgia. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/a-need-based-financial-aid-program-for-georgia/#_ednref13

[35] Bergson-Shilcock, A. (2020, August 18). Funding resilience. National Skills Coalition. Retrieved August 28, 2023, from https://nationalskillscoalition.org/resourrece/publications/funding-resilience/

[36] Angel, S. (2021, January). Green-light Georgia driver’s licenses for all immigrants. Georgia Budget and Policy Institute. https://gbpi.org/green-light-georgia-drivers-licenses-for-all-immigrants/

[37] Prosperity Now. Baby bonds. https://prosperitynow.org/baby-bonds