As 90-degree summer heat hangs over Manchester, residents do their best to stay cool. In one window, a fleece red-and-white holiday blanket hangs to block out the sun. In another, socks are crammed into the window gaps to prevent any AC air from leaking out.

On the west side, Dupont Splash Pad is a popular way to stay cool. Families stretch out in the grassy shade, while adults and toddlers walk under colorful fountains for relief. A girl’s pink skirt flops up and down as she jumps on the fountains spurting up from below, willing the timed jets of water to return quickly.

Manchester resident Judy Harding said she’s certain the city heat has been getting worse.

Harding lives in a public housing apartment building. It stands tall amongst just a few trees, baking in the afternoon sun. Fans line several window sills.

“The humidity has been terrible. There’s no doubt the planet is warming up,” she said.

Harding’s observations aren’t unfounded. Evidence from the 2021 New Hampshire Climate Assessment suggests that higher temperatures are here to stay. The report found that temperatures are expected to continue rising through the end of the century, and the frequency of extreme temperatures is expected to increase. Depending on the extent to which human activity continues to contribute to climate change, the state could experience 20 to 60 additional days of 90-degree heat each year.

This means summer heat is getting more dangerous, and even deadly. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that an average of 702 heat-related deaths take place each year in the United States. However, a report from the Environmental Protection Agency notes that heat-related deaths are not always recorded as such, and as a result, these deaths often go undercounted.

In a state that isn’t built to handle the heat, protecting those most vulnerable may mean rethinking state infrastructure and resources. For cities, increasing neighborhood tree coverage may be key. Some states have also started looking at cooling assistance programs, but it’s unlikely New Hampshire will join them anytime soon.

Harding said she worries about the health risks for seniors like her. While she enjoys sitting outside to have “gossip time” with her neighbors, she said some of them have been coming out less often because of the heat.

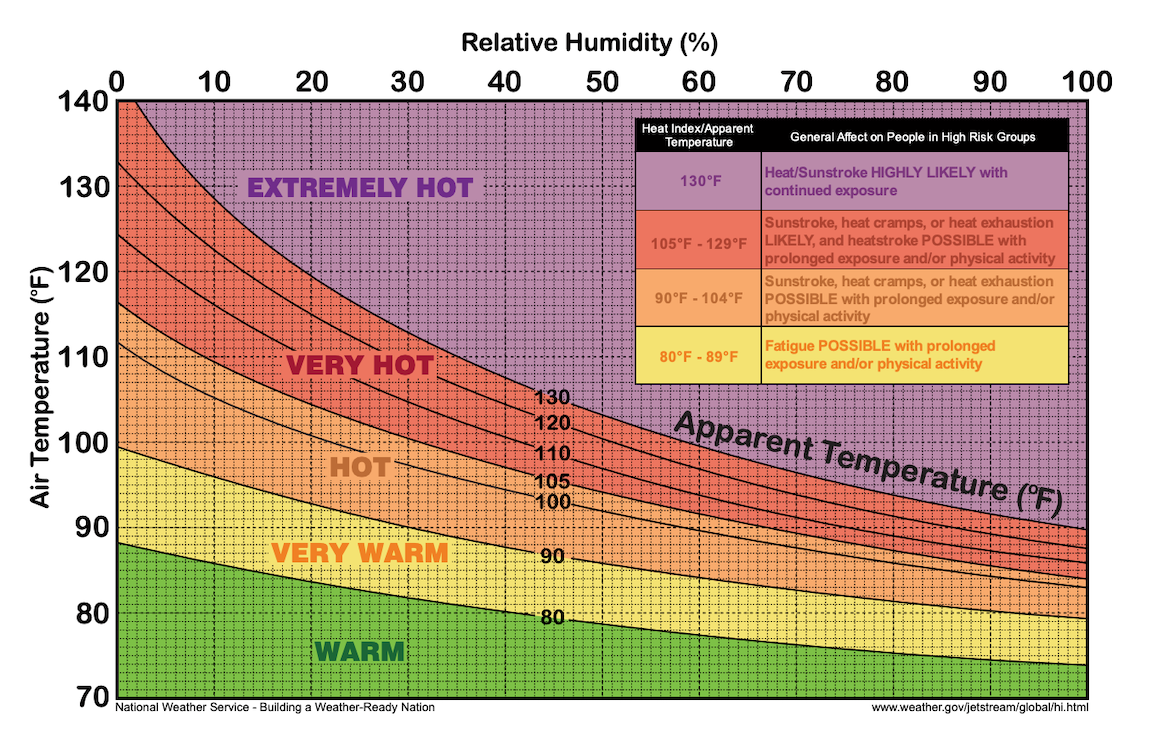

Data shows Harding and her neighbors have cause for concern. A 2017 study of heat-related deaths in New England found that emergency room visits and deaths increase significantly on days with a heat index of 95 degrees versus a heat index 75 degrees.

“It’s important to know that a heat index is not temperature, it’s a combination of temperature and humidity,” said Dr. Paul Friedrichs, a member of New Hampshire Health Care Workers for Climate Action.

According to Friedrichs, many health conditions can increase the risk of heat-related illness and death. Those with chronic heart conditions or kidney disease, pregnant women, and individuals on medications with side effects like reduced sweating should take extra precautions. People over 65, children, and infants are also at increased risk.

Vulnerable communities hit the hardest

New Hampshire’s infrastructure was not built with the heat in mind, and experts say that is impacting some communities more than others. The state’s cities are especially vulnerable because urban buildings and roads absorb and re-emit heat more than areas with tree coverage, plants, or bodies of water.

“When you get a 98-degree day and the evenings aren’t that cool, cities just kind of hold on to that and it just builds and builds and builds over days,” said Jeffrey Hyland, a New Hampshire architect at Ironwood Design Group.

Hyland said trees and greenspace in urban areas can play a key role in reducing the buildup of heat. Greenspaces are open-space areas with plant life, such as parks or community gardens. Areas shaded by trees and other greenspace can be anywhere from 20 to 45 degrees cooler than the hottest unshaded areas, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Arnold Mikolo, an environmental justice advocate with the Conservation Law Foundation, says that in the city of Manchester urban greenery is noticeably absent from lower-income neighborhoods compared to wealthier ones.

“So then there is this extra burden on low-income neighborhoods, who have to pay for (more) air conditioning,” he said.

Mikolo’s observations are backed by a national 2020 study published in the Journal of Climate. The study finds that investment in urban greenspace has historically been inequitable, leaving poor urban communities and communities of color disproportionately exposed to extreme heat.

Cooling centers are one short-term option in place to protect people in the case of a heat wave. These are public locations, such as libraries or shelters, that are open for extended hours to provide access to a cool space during a heat advisory period.

With the number of heat waves expected to increase, Mikolo sees cooling shelters as a temporary fix. Instead, he emphasized the role better urban design can play as a form of justice for vulnerable communities.

“I know that this takes some time, but I really think [increasing treespace] is what’s going to be the best solution right now,” he said.

This year, Mikolo worked with the city of Manchester to apply for a U.S. Department of Agriculture grant intended to expand access to greenspace in disadvantaged communities. Mikolo believes that if the city receives some of the $1 billion available, the funding could provide for as many as 500 trees a year in disadvantaged communities.

‘I don’t think there are enough resources available for something like this’

For now, air conditioning is still the greatest protective measure for these at-risk communities, according to the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services. However, with increasingly high electric costs, air conditioning is often not accessible to those who need it most.

“If a family has to choose between paying an electric bill and putting food on the table for their children, they are going to choose food,” said Mikolo.

While some states have launched forms of cooling assistance to cover air conditioning or utility costs, New Hampshire remains focused on fuel assistance for the winter months.

Stephen Tower, an attorney for New Hampshire Legal Assistance, does not expect the state’s Department of Energy to initiate a cooling fund anytime soon. He said currently the funds would have to come from the same pool of low-income home energy assistance funding, which is used in the winter heating period.

“There’s a tension between using that money for cooling in New Hampshire as the state gets warmer, and having that resource available for heating in the winter,” he said.

Nebraska is one state that has made the transition to offering both heating and cooling assistance through LIHEAP funding. Households can receive assistance from June 1 through Aug. 31 if they qualify for LIHEAP funding, and have a household member who is older than 70 or has a pre-existing medical condition aggravated by heat. Qualifying households can also receive financial assistance for the installation of an air conditioner.

There are some non-governmental bill assistance programs in New Hampshire, such as Neighbor Helping Neighbor (available to customers of Eversource, Liberty, and Unitil) and Project Care (available to customers of the New Hampshire Electric Cooperative), which help to cover bills in emergency situations.

During the winter months, New Hampshire Public Utilities Commission rules prevent the shutoff of a customer’s utility service for nonpayment unless the customer’s overdue amount is relatively high. However, no such protection exists for those experiencing financial hardship during the summer months.

With no other resources in the state, workers at one home health care agency took it upon themselves to help clients with air conditioning needs. Started in 2000, Project CoolAir provides free air conditioning units to those in need throughout Rockingham County.

“We’ve had some of those summers where it’s just, it’s 90 to 100 degrees every day,” said Program Director Mary Jane Walsh. “And then [during] those summers we get several referrals every day through August.”

The program relies entirely on donations to serve those in need. Those over 60 with a health condition can be referred to the program by anyone and those under 60 can qualify with a doctor’s statement confirming a health condition that merits need.

“Something as simple as an air conditioner for you or I, for them, that means the difference between living in their home safely or not being able to stay there,” she said. “So I don’t think there are enough resources available for something like this.”