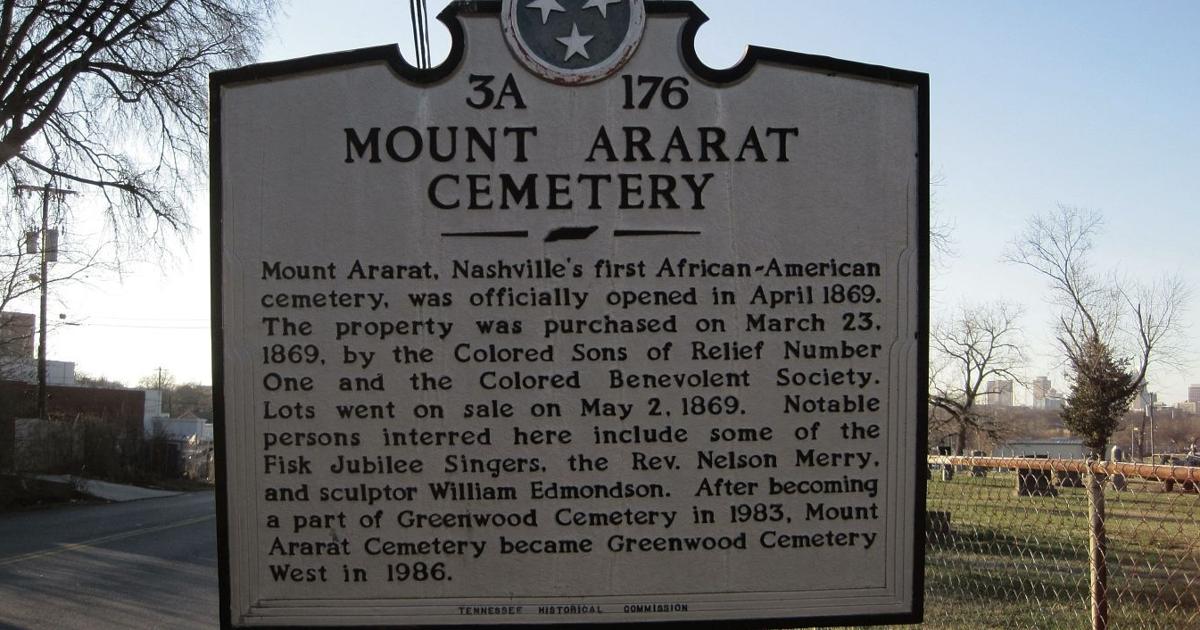

Ever since I first read Leigh Ann Gardner’s To Care for the Sick and Bury the Dead: African American Lodges and Cemeteries in Tennessee (and let me be clear about any conflicts of interest — I was the acquiring editor on that book), I have been fascinated by the story of the first Chinese person to die in Nashville: Chang Ze Yow, or as he was known to Nashville, Johnson McGhee. Chang died of tuberculosis on Aug. 26, 1878, and was buried at Mt. Ararat. That’s because no one was sure what to do with his body, because they weren’t sure what race or religion he was, so they didn’t know what cemetery to put him in.

A reporter from the American wrote a short piece on Chang’s passing. It reads, in part:

Shing Lee, the laundryman on Cedar street, a cousin of the deceased, refused to assist in disposing of the body, or to have anything whatever to do with it.

In order to learn something of the history of McGhee, a reporter of the American visited his former partners in the laundry business, three in number, at No. 24 North Cherry Street.

Since this is 1878 we’re talking about, the rest of the article is in racist dialect, so I’m not going to quote it. But we do learn from it that McGhee was around 37 years old and had been in Nashville roughly two years. He came into the country through New Orleans 10 years before his death and spent some time living in Arkansas. The article concludes, “After having been informed by a colored woman, who was present, that the burial would take place at Mt. Ararat Cemetery (colored) this morning at 10 o’clock, the reporter thanked the Chinamen and withdrew.”

The more I think about this, the more it blows my mind. Nashville is always talked about like we were so provincial until, like, 30 years ago, and as though we still weren’t really a diverse city until recently. But we had a small — apparently very small — Chinese community here in Nashville in 1878. Of all the languages I’d think you might hear in Nashville in the 1800s, Chinese wasn’t on my list.

The community, such as it was, seemed centered around Cherry and Cedar, which is now Fourth and Martin Luther King, which is an intersection I seem to be spending a lot of time around lately. Shing Lee had one laundry at 21 Cedar in the 1878 city directory, and Wah Lee had another laundry at 28 N. Cherry. By process of elimination, this must have been where Chang worked. In the 1880 census, there are two Chinese guys living on Cherry — John Ahman and Jim Gowe — who have a Black woman servant. It seems plausible that this woman is the woman who informed the American reporter that Chang would be buried at Mt. Ararat, and likely that Ahman and Gowe were the men the reporter was speaking to.

So just to be clear, there’s one laundry run by Shing Lee and another laundry run by Wah Lee, John Ahman, and Jim Gowe. Chang was, supposedly, Shing’s cousin, but worked with Wah, John and Jim. By 1880, Chang was dead, and John and Jim were both sick as shit with lung ailments, which I would guess is a hazard of working with cleaning chemicals back then.

Wah, however, did not die. Instead he went to Louisville. When he came back, he had a wife. Ten years after the death of Chang, Wah and his wife were in court for assault. The story of this assault made me laugh for a few reasons. For one, the Nashville Banner’s coverage of it is grumpy — “Wah Hing, Sam Wah, Wah Lee, or Wah Hee, whichever may be his name.” Everything I know about Chinese naming conventions I learned from Wikipedia and my cousin-in-law who regularly visits family in China. I will impart that knowledge on you now: 1. Chinese people do have a lot of different names based on various circumstances. If you don’t understand how this might work, find yourself a Bubba and ask him what his grandma calls him. You know his friends all might call him Bubba, but she calls him Charles as sure as anything. His dad calls him Charlie and somehow no one is confused. 2. Chinese people have a lot of different words for relatives, depending on how they’re related to them. Oldest uncle on your dad’s side has a different word than middle uncle on your mom’s side. But if you go to China and embarrass yourself enough by failing to keep these all straight, your family may tell you to just call everyone older than you aunt and uncle, everyone around your age sibling or cousin, and everyone younger than you niece or nephew. This is why I’m somewhat reluctant to say with certainty that all these men were related in the ways the papers claim they were related, or that Wah Lee was somehow being evasive or intentionally confusing by being called a bunch of different things.

Anyway, let’s leap into a pile of racism and try to detangle the assault. Some Black “boys” were saying racist things to Wah. There’s some indication in the story that at least one of these people may have been an actual child. Wah stole the hat of one person hoping it would cause his mother to come to see Wah and he could tell her what her son had been up to. So, this person may indeed be a child. He is unnamed in the story. Jerry Claiborne, who is at one point described as a “young colored man” — so I think we can guess adult, but just late teens/early 20s — gets into the fracas between the child and Wah. Now Wah’s wife comes out of nowhere with a butcher knife! Who brings a butcher knife to a retaliatory hat theft?! Am I the luckiest writer in the world that I get to write a sentence like “Who brings a butcher knife to a retaliatory hat theft?!” Feels like it.

Wah was fined $10. His wife was fined $5. Claiborne “was fined $5 for language calculated to provoke a breach of peace.” The judge then lectured Wah for not going to the police instead of taking the law into his own hands. End of story, right? No, not for this unnamed Banner reporter. This Banner reporter still has space to fill, and he’s going to fill it with a huge paragraph devoted to more grouching about Wah’s name and gushing over how handsome Wah’s baby is. I want every news story to end this way: with a random account of whether any local babies present are good-looking or not. Does the baby, George, have anything to do with this story? No. He’s not a witness for the defense. He wasn’t a participant in the fight. He’s just a baby in the eyeline of a reporter. Is his handsomeness newsworthy? I guess so.

I’m already out here trying to convince current Banner editor Steve Cavendish that he ought to take up writing weird prose poems about the news, like James Stahlman did back in the Banner’s heyday — but no, we don’t need more dudes writing verses about the news. We need more stories that end with baby scrutiny. Everyone who writes for the Banner should have to provide Nashville with solid information about how our babies look.

But here’s where this post takes a turn for the completely ludicrous. Saturday morning I walk into the Tennessee State Museum and I see museum staffer, Jeff Sellers, standing there. I ask him, “Jeff, when would you guess the first Chinese people to live in Nashville were?” And he’s like, “I know just the person you should talk to — Joyska Nunez-Medina.” Turns out Joyska wrote a whole big blog post on why and how Chinese people even got to the South in the 1870s for the Tennessee State Museum website. You’ll be unsurprised to learn that it was horrific and involved Nathan Bedford Forrest and an effort to undermine the labor market that was now filled with Black people who expected to be paid. I cannot stress to you enough how I simply walked into the state museum, shouted out a research question, and was put in front of a person who had been researching this very thing, which had nothing to do with what either of us was doing that morning.

Joyska told me that most Chinese immigration centered on Memphis and that there were even small villages for Chinese people set up in Arkansas. This fits with what we know of Chang Ze Yow’s life, since the American reporter said his co-workers said Chang had been living in Arkansas before coming to Nashville.

I tried really hard to see if there were descendants of these men still in Nashville, but I ran into a problem. A lot of these guys married Irish immigrants, and within a generation their last names were often very Americanized and their family first names tended to be very Catholic. Take Hong Pang, who lived in Nashville before settling in Indianapolis. He married Mary Alice Dodd, and one of their daughters was named Madonna. And obviously, we remember handsome little George Lee. There’s no obvious choice for who he grew up to be, but also no obvious match in the death records. Judging by all the documents I’ve looked at, white Southerners didn’t have consensus on how Chinese people fit into racial categories. I saw Chinese men classified as “white” and “mulatto” and “Ch” just depending on who was doing the classifying. Irish people were in a similar situation in the 1800s — they weren’t white the way that white people at the time defined it. So it makes sense that people caught in this limbo of not being white but not being Black would marry each other, especially in parts of the country where there just weren’t any Chinese women.

But it also means that, if you have a very common Southern last name like Lee, in a generation or two, it was very easy for you to just get swept up into being white. Let’s just say George did stay here. If you were one of his descendants, you might be at least a fifth-generation Nashvillian by now, and you might not even know that one of your ancestors came here from China 150 years ago.